Adventures in Bookland: Shell by Paula Rawsthorne

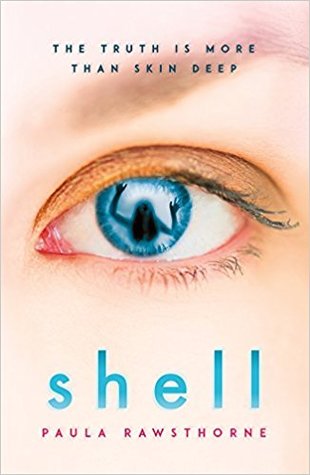

Shell by Paula Rawsthorne

To review this book I first have to tell you about another book I read many years before. I grew up reading a series of books that I later discovered are known as Robert A. Heinlein’s juveniles. Books such as Space Family Stone, Have Space Suit, Will Travel, Starman Jones. There was nothing juvenile about them though, other than the protagonist being young: the stories set the template for the language of modern science fiction as well as being taut, tense, thrilling tales with not a word out of place. I still have these books, and reread them with pleasure. I owe Heinlein a huge debt, both for demonstrating the art of storytelling in its pure form and for the life lessons he subtly imparted in these stories, the foremost one being his dictum TANSTAAFL (‘there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch’).

So, as I advanced into my second decade, I was delighted to find some new books by one of my favourite authors in the adult section of the library. I was not a socially gifted child and the awkwardness had not improved as I got older – I probably knew the librarians at the library better than any of my peers. The highlight of my week remained getting home from the library with my new pile of books and deciding in what order I would read them. But that week there wasn’t any difficulty in choosing. Sitting on top of my pile was the thickest Robert Heinlein book I had ever seen. Previously, the longest book of his I had read came in at about 250 pages: this one was over 500! SF heaven waited and I plunged in.

A couple of days later I emerged about as confused as a 14-year-old boy could be. The story was a bit… different. An ageing billionaire has the world’s first brain transplant, but ends up in the body of his young and sexy secretary who was conveniently murdered just as the doctors were looking for a convenient donor (and no, there’s no interesting plot point here involving the billionaire’s minions murdering someone close at hand, just authorial arm waving). What’s more, the secretary turns out to still be mentally alive in the billionaire’s new body; the two of them end up cohabiting the body and talking at length – and I do really mean at length – inside the body’s shared mind. So, what would do if you suddenly found yourself in a young body of the opposite sex having been slowly sliding into decripitude? Well, in this case, billionaire and secretary end up shagging everything that moves, having a baby from the billionaire’s frozen sperm and, what was possibly most surprising for a 14-year-old boy with absolutely no experience of such things, having nipples that went ‘sprunnnggg’ at every available opportunity and sometimes completely at random. Suffering the embarrassing effects of spontaneous teenage tumescence, which also seemed to happen entirely on its own, often for no apparent reason whatsoever, it did not seem unlikely that women’s nipples might behave that way too. After all, I obviously had absolutely no knowledge of such things. It was an image that engraved itself deeply into my teenage mind: testosterone and imagination can engrave each other very deeply.

It was a truly dreadful book, one that it is hard to believe a writer as good as Heinlein might actually write (and then I read some of his other late fiction and sadly realised that he had gone from being a storyteller to a didacticist). Thankfully, Paula Rawsthorne avoids absolutely all of this apart from the basic brain transplant premise in her book. In Shell, Rawsthorne examines devouring mother love, the sort of love that destroys rather than lets go, and takes it to its logical conclusion: a mother who won’t let her daughter die but brings her back in a new body. This body, unlike the one in I Will Fear No Evil, does not carry the ghost of its previous soul, and is all the better for it. The protagonist, Lucy, has only to contend with the exterior, of finding herself in a body that is actually better than her old one, and the price that was paid in obtaining this new body for her. The story examines these issues in the context of the story rather than preaching them through the interminable inner dialogues of I Will Fear No Evil (normally only punctuated by ‘her’ nipples going ‘sppprunnnggg’) as well as presenting one of the best devouring mothers I have read. I’m pretty sure the author is British but she carries off the American setting with aplomb. A fine story for intelligent readers and one that will, I hope, enable me to finally leave the enduringly bad taste of Heinlein’s book behind. For Rawsthorne finally, I hope, disinfecting my imagination of nipples going ‘spprunnggg’ I am profoundly grateful. Some books change your life, others cleanse your soul. Shell has done the latter for me.

0 Comments