The Battle of Heavenfield AD 634

The combatants

Oswald (603/4 – 642), exiled prince of Northumbria

Forced into exile as a 12-year-old boy when his uncle, Edwin, killed his father, Æthelfrith, and took the kingdom of Northumbria, Oswald grew to manhood in the kingdom of Dál Riata. While there, Oswald and his exiled family, previously pagan, embraced Christianity with varying degrees of fervour, and Oswald himself gained a reputation for martial valour and Christian piety. When Uncle Edwin was killed by Cadwallon, King of Gwynedd, Oswald remained in Dál Riata, only launching his own effort to retake the throne after Cadwallon had killed two other pretenders, both relatives of Oswald. Victorious at the Battle of Heavenfield, Oswald brought monks from Iona to preach the new religion to the Northumbrians, in the process creating institutions that were able to survive Oswald’s own death in battle in 642. A cult rapidly developed around Oswald following his death, with the martyred king – he died in battle against the pagan king of the Mercians – becoming a popular saint in Britain and Germany.

Cadwallon ap Cadfan (d.634), King of Gwynedd

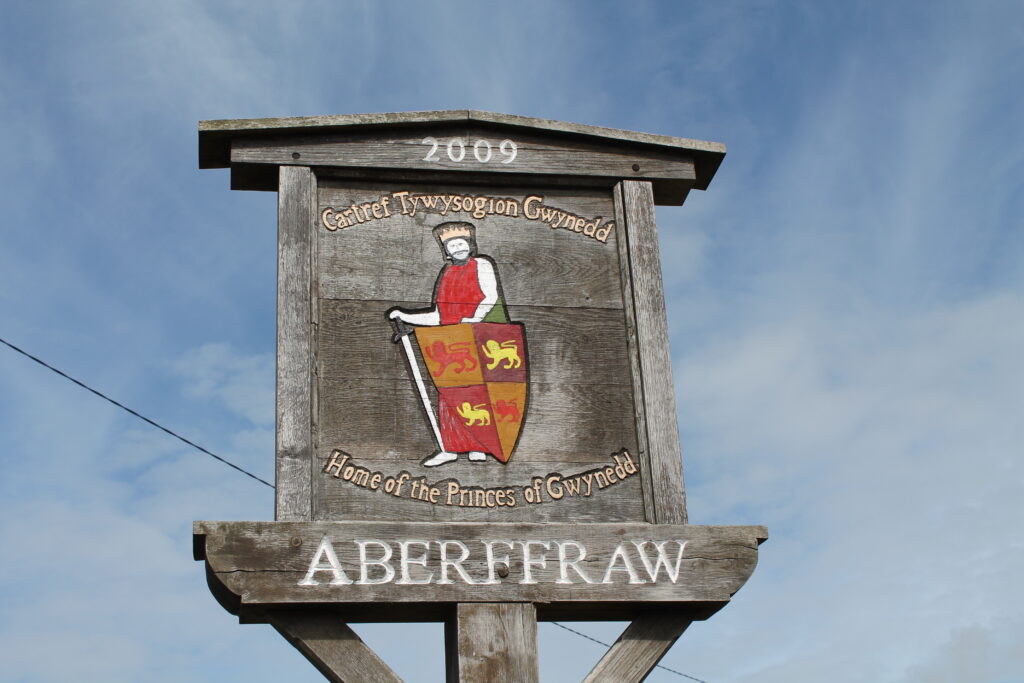

Cadwallon was the subject of vituperation in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, the villain around whom the first half of the book is structured. In Bede’s account, he was a violent marauder, bent on exterminating the Northumbrian people. But for the Britons, Cadwallon was their last great champion, ‘the fierce affliction of his foes, a lion prosperous over the Saxons’. On the Isle of Anglesey, the breadbasket of the Kingdom of Gwynedd, the kings had their palace at Aberffraw. There, Cadwallon raised a memorial stone, visible today inset into the wall of the Church of St Cadwaladr. CATAMANUS REX SAPIENTISIMUS OPINATISIMUS OMNIUM REGUM. ‘King Catamanus, wisest, most renowned of kings.’ Catamanus is the Latin form of Cadfan, Cadwallon’s father. The brutal warleader of Bede’s account raised a Latin inscription praising the wisdom of his father. History, as written by different sides.

The Battle

It was a bleak place to die. The moors rose steeply from the east bank of the Devil’s Water, their flanks bare of cover. The river itself, that had provided the remnants of the retreating army with some cover at the start of the long rout, now boxed them in. Coming to another stream, Denis Brook, that fed the Devil’s Water the leader of the retreating men signalled those still left with him to turn and make a stand. The moors rose up to the south. There was no escape that way, not with their pursuers following so close behind. The only chance was to buy a little time, to bloody the hunters so that they had to stop and regroup, and then attempt to escape.

Cadwallon, King of Gwynedd, the most successful warlord in Britain, the killer of kings and the hope of his people, ranged his retainers beside him, anchoring the flank against the river. There were so few of them now that he could do nothing to protect the right wing of his shield wall. They waited. They did not have to wait long.

The man leading the pursuers had been given a nickname, Lamnguin, by the people with whom his mother had sought safety when he was still a boy. Lamnguin meant ‘white blade’. But it was not white now. The man’s name was Oswald.

With the Denis Brook at his back, Cadwallon prepared to make his stand. The moors, bare of trees in the 7th century as they are bare today, looked down with the detachment of geology. Humans many generations earlier, during the Neolithic, had stripped the hills of their tree cover, their stone axes proving as adept at deforestation as later tools of iron and steel.

The final battle was brief but brutal. At its end, Cadwallon and the men of his household lay dead, their bodies stripped of ornaments and armaments.

The Battle of Heavenfield was over. Oswald, Northumbrian ætheling in exile, had returned to reclaim his crown. Ætheling is an Old English word meaning a man who is throne worthy. Among the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that had been established in the east and central regions of Britain there was no settled system for the transmission of power – how could there be, when power was something that was taken, and kept, with the sword.

The Background to the Battle

To be a king of one of these kingdoms did normally require some connection to the ruling family but just as important for the succession was the ability of a claimant to the throne to gain the support of the leading men of the kingdom. If all else failed, power could simply be grabbed, taken in battle and then cemented by further warfare. If this makes early-medieval Britain sound like a chaotic place of incessant warfare, that is pretty much what it was like. This was a time when a warband of 50 men might win a kingdom. A later law code, promulgated by King Ine of Wessex in 694, defines an army (here) as a group of 35 or more men.

So it is likely that, as Bede says in his account of the Battle of Heavenfield, Oswald was leading a small band of men when he confronted Cadwallon. The name of the battle is misleading, for it commemorates the place where Oswald camped on the eve of the battle. There is a church at Heavenfield today, a largely Victorian rebuilding of an earlier Norman church that was itself built over an early Medieval building. The church is named, naturally, St Oswald, for the warrior king was acclaimed a saint following his death in 642. Of course, the church postdates Oswald’s camp. Bede informs us that Oswald camped on the northern side of Hadrian’s Wall and that monks from Hexham had later raised a church on the site.

Oswald’s small warband was relying on the tactics of surprise and assault that Oswald had learned during his years spent with the kings of Dál Riata. In that kingdom, which stretched from Northern Island to Argyll, the obligations of the three clans of the kingdom were assessed in the numbers of boats and warriors each clan had to provide to the king when called to the kingdom’s defence. The Dál Riatans pursued the tactics of surprise and sea-borne assault that would serve the Vikings so well three centuries later – and Oswald had learned these tactics during his formative years, when he had earned his nickname fighting with the king’s warband.

While Oswald could not arrive by sea, his aim was to attack Cadwallon before news of his presence could reach the King of Gwynedd. Oswald and his men had outridden rumour, most likely galloping along the Stanegate, the west-east Roman military road that ran just south of the Wall and predated it. Near St Oswald’s Church, that commemorates Hefenfelth, the ‘heavenly field’ where Oswald and his men camped, archaeologists discovered the remains of what is prosaically called Turret 25B, one of the milecastles of Hadrian’s Wall. Nothing remains above ground, but it would have made a good night camp for Oswald and his men, providing shelter and, since it lay on the declining slope of a ridge, cover from eyes looking from the direction of Cadwallon’s camp.

It must have been a tense night. During the course of it, according to the account written by Adomnán, abbot of Iona from 679 to 704, Oswald had a dream vision of St Columba, the founder of the monastery on Iona and the man whose spiritual legacy lay over the Irish Sea and its surrounding lands. In the vision, the saint promised Oswald victory on the morrow. For Oswald, who had gone into exile as the pagan son of pagan Anglians, had become enchanted by the new faith of the Holy Isle during his growing up, and embraced it wholeheartedly. In Bede’s account Oswald also raised a cross before his warband, holding it in place while his men made it firm, then kneeling with his men to ask God’s blessing for their cause.

This was an age when men judged heaven’s favour by the most fundamental of metrics: those who won and those who died in battle. The monks of Iona, from whom Oswald had received the new faith, had seen in their young protégé a man who could do something no one else had been able to do: bring the faith to his pagan brethren. Yes, Augustine, the Italian emissary of Pope Gregory the Great, had landed in Kent in 597, but after its initial success the Augustinian mission had stalled. The sponsorship it had enjoyed through the patronage of Æthelberht, King of Kent, the most powerful king among the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Britain, had died with Æthelberht.

There had been northern success when Edwin, King of Northumbria, Oswald’s uncle and the man who had killed Oswald’s father, converted to Christianity. But then Edwin fell in battle to Cadwallon the nascent Christian kingdom Edwin was trying to set up collapsed too. This was very much the pattern of early-medieval Britain. A warlord would rise, winning power and prestige through success in battle, and thereby attracting glory hungry young men to his warband. The warlord would expand his power, forcing other kings to pay him tribute, with regular skirmish wars to exact further treasure, until a battle too far ended in his utter defeat and death, with the consequent dissolution of whatever rudimentary kingdom the king had built up. Edwin’s kingdom dissolved on his death.

But after defeating Edwin, Cadwallon, unusually, did not return to Gwynedd. Instead he remained far from home in Northumbria, killing two further claimants to the Northumbrian throne, Edwin’s cousin Osric and Oswald’s half brother, Eanfrith.

Bede’s portrays Cadwallon as a rapacious predator, bent on destroying the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria and its people. His portrait is one-sided: for the Britons, the native people of Britain, Cadwallon was a champion, their ‘furious stag’ who broke from the mountain strongholds to which they had withdrawn to reclaim their inheritance. As such, Cadwallon’s long stay in Northumbria, which had become the pre-eminent Anglo-Saxon kingdom under the rule of King Edwin, makes some sense. Cadwallon, like most of the Britons, was a Christian, a man who was still sufficiently versed in Romanitas to have a Latin epitaph carved on his father’s gravestone. But the monks of Iona, the most important spiritual centre in the Irish Sea, decided to favour their own man, Oswald, in the struggle for the throne of Northumbria. The descendants of Cadwallon, the Welsh, included in the Mabinogion their lament for their fallen champion and a veiled reference to the treachery of Iona.

From the plotting of strangers and iniquitous

Monks, as the water flows from the fountain,

Sad and heavy will be the day for Cadwallon.

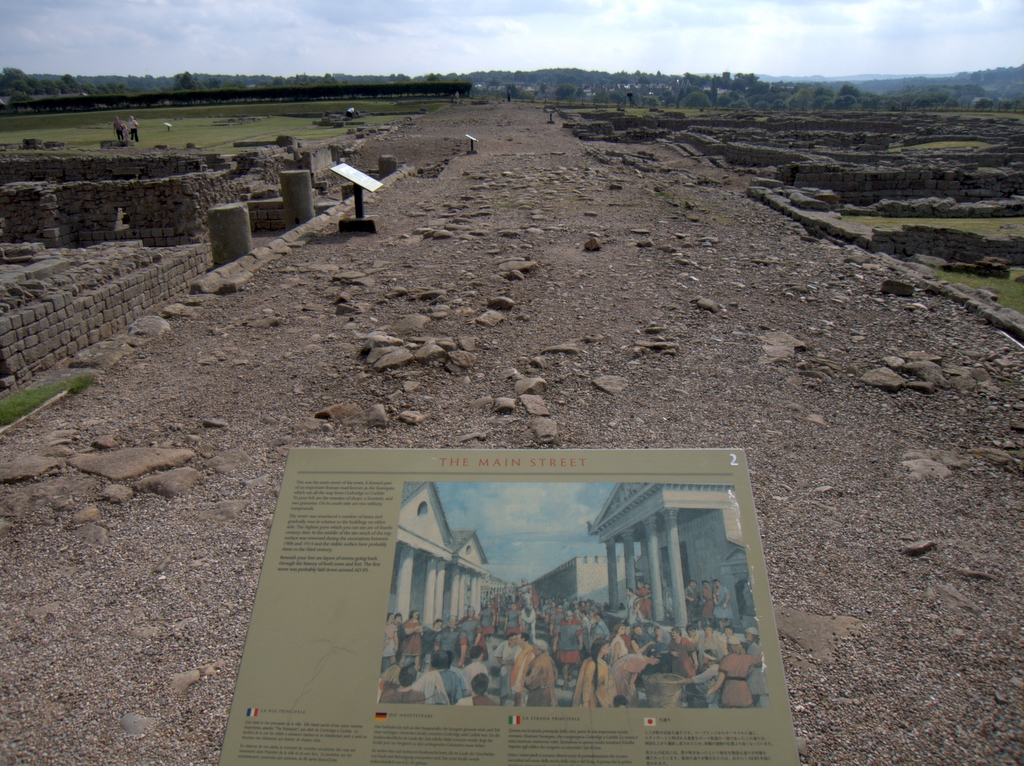

Cadwallon’s army had been on campaign for a more than a year. The initial warband, the warband that had defeated and killed kings and made Cadwallon the most successful warlord in Britain, had bloated and swelled with hangers on and the loot of many victories. Camping somewhere near Corbridge, at the junction of Dere Street and Stanegate, Cadwallon could guard the bridge over the River Tyne. But Oswald had advanced faster than the news of his landing in Britain could reach Cadwallon. Using the tactics of surprise and aggression learned from his time in Dál Riata, Oswald attacked at dawn. With his camp thrown into confusion and panic, Cadwallon attempted a fighting withdrawal with what men he could summon to his call.

The battle turned into a series of strung out skirmishes. Rather than retreating south down Dere Street, Cadwallon fell back along the Devil’s Water. The river has its source in the moors south of Corbridge, today part of the North Pennines AONB. Its not an obvious line of retreat. Most likely Cadwallon was forced that way. His end came, as Bede reports, by the Denisesburn, the Brook of Denis. While Denis Brook might have been well known in Bede’s time, its name was forgotten in later years, and with it the location of the battle’s denouement. It was only the discovery, in the 19th century, of a 13th century charter that made over land to Thomas of Whittington between Denisesburn and Divelis that the location became known again, for the Divelis is another name for the Devil’s Water. There Cadwallon died and Oswald claimed the throne of Northumbria.

King now, by the grace of battle, Oswald gave to the monks of Iona another island, Lindisfarne, within sight of his ancestral stronghold on Bamburgh and with Aidan, abbot and bishop of Iona, he set about doing something that no other king of early-medieval Britain had succeeded in doing: making a kingdom that could survive his death. Together, king and abbot embarked on that most delicate and difficult of tasks: the making of a civilisation.

0 Comments