Brothers In the Sky

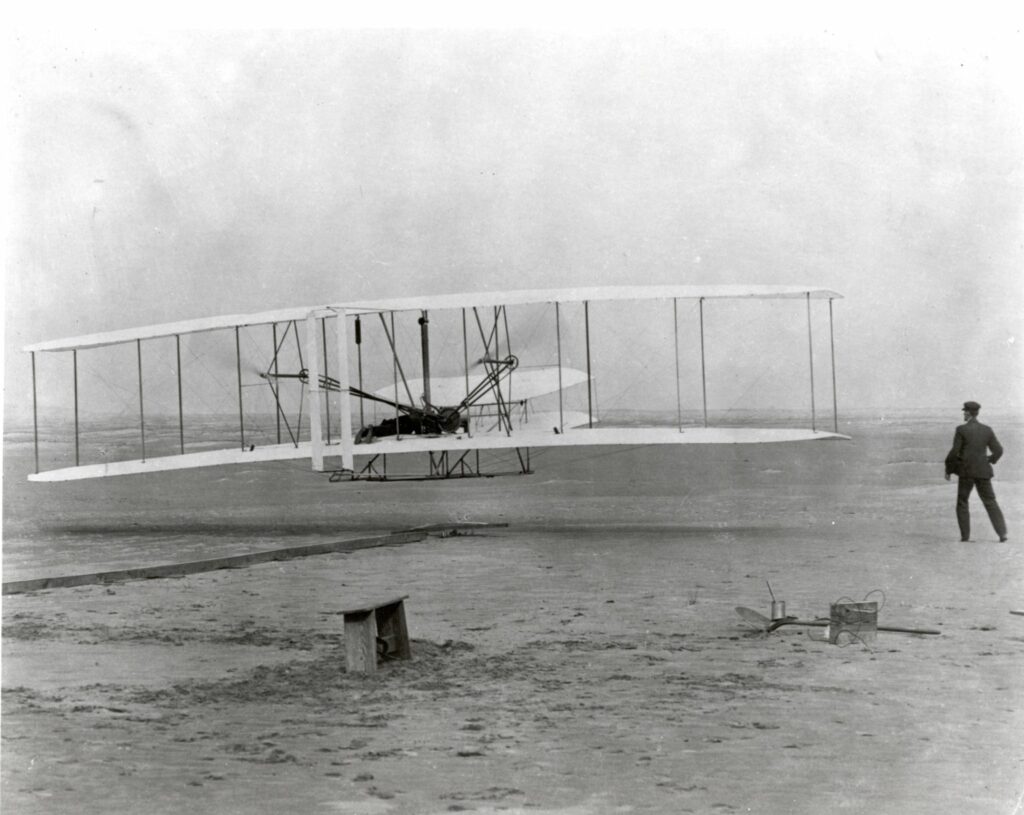

The date is famous. 17 December 1903. On that Thursday the Wright brothers, Orville then Wilbur, made the first controlled powered flights in a heavier-than-air machine. In all, there were four flights that day, two for each brother. Five people watched history being made. Reports reached the press. And then…nothing happened. Barely any newspapers covered the story and the news faded away. No one could believe a couple of bicycle makers from Dayton, Ohio, a place as far from the beating heart of things then as it is today, had done what other better known, better educated and better connected people had failed to do. But it was precisely the roots the Wright brothers had in Dayton that made possible their extraordinary achievements. Of these roots, none were more important than their parents.

Milton Wright, father to the clan, was minister then bishop of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. He fostered in his sons a love of reading and free intellectual inquiry that stemmed from his own interest in debate; if the boys, growing up, were engaged in some important investigation he happily turned a blind eye on them skipping school to concentrate on whatever new device they were constructing. However, it was from their mother, Susan, that the boys inherited their engineering flair: she constructed her own household appliances and made toys for the boys. Susan had met Milton during her studies at the United Brethren college in Hartsville, where she was studying English literature. Thus Wilbur and Orville grew up in a household predicated upon a deep commitment to learning, unshakeable faith (which the brothers also transferred into confidence in their work) and adherence to principles.

Milton and Susan had other children too: twins who died in infancy, two other sons, older than the flying brothers who made lives of their own, and the youngest, Katharine, who would share house, conversation and duties for many years with her famous brothers.

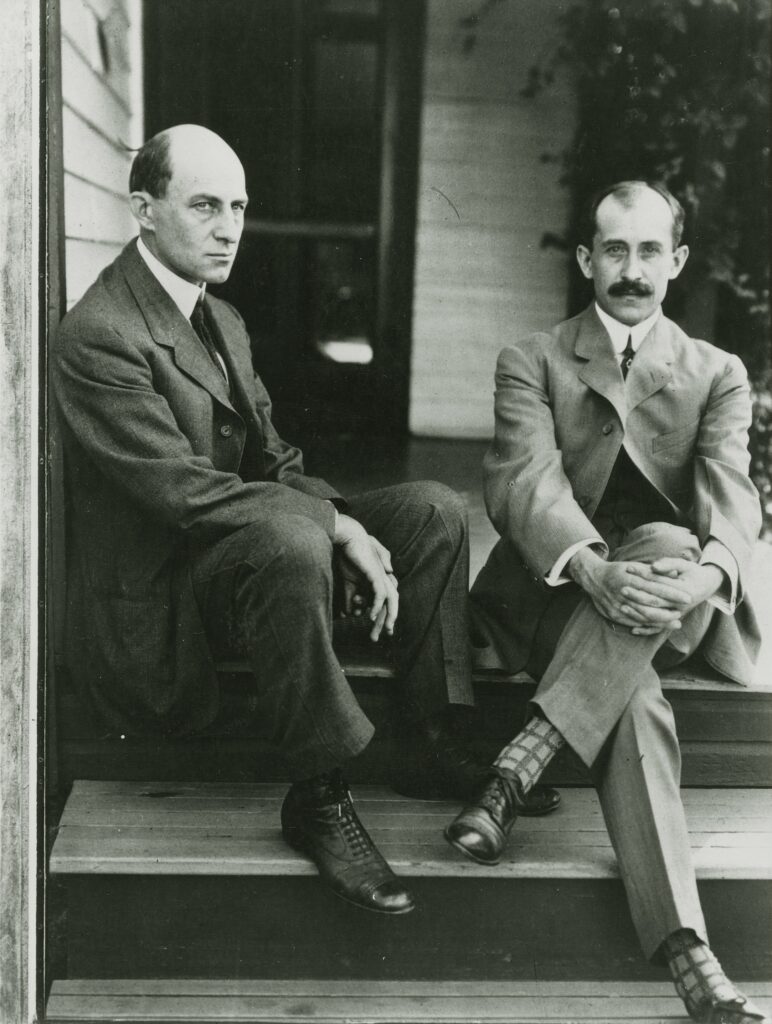

Wilbur Wright, born 16 April 1867, was the elder. In photographs of the pair he is the intense, balding figure with penetrating eyes. Orville Wright, born four years later on 19 August 1871, looks generally more avuncular and wears the thick moustache typical of the era. Despite the difference in age, the pair were inseparable. But separation was in the offing as Wilbur neared graduation from high school. A brilliant student – his test scores were in the 90s for everything – and an outstanding athlete, Wilbur was destined to fly high, educationally speaking: he was set for Yale.

Then, it happened, and everything changed. During an ice hockey match, a hockey stick smashed into Wilbur’s face, knocking out most of his upper front teeth. Wilbur suffered months of pain, followed by bouts of depression and withdrawal. Yale was out of the question. What’s more, their mother, Katharine, was ill with tuberculosis. Wilbur became her carer and, having retreated to the confines of the house, he read and read and read.

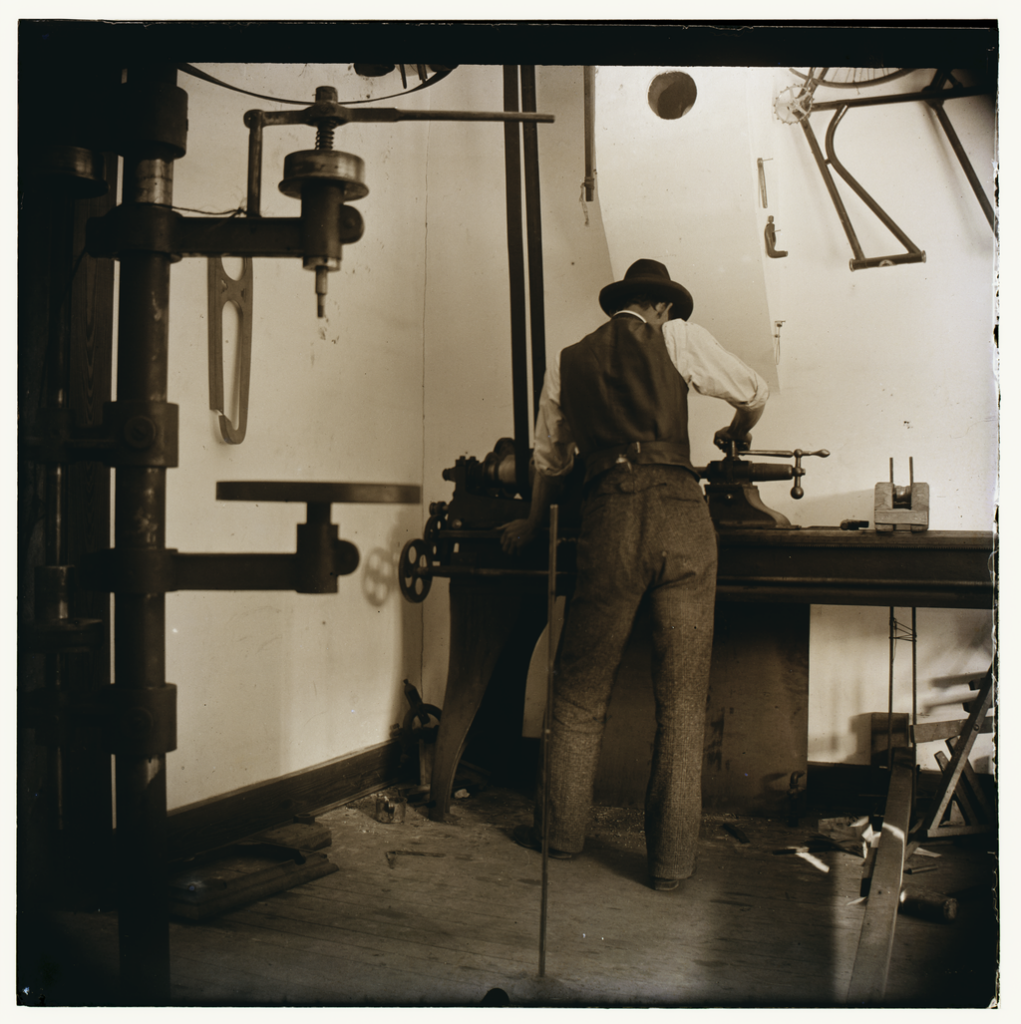

For his part, Orville had become fascinated with printing and, while still at school, built his own printing press using a tombstone, a spring from a horse buggy and scrap metal. Milton Wright credited the care Wilbur took of his mother for extending her life far beyond what was thought possible with tuberculosis, but in 1889 Susan Wright died. Wilbur, slowly emerging from his isolation, joined Orville in his printing business. In response to the national bicycle craze, in December 1892 the brothers started repairing bicycles and by 1896 they were building them too. They were assembling the skills they would need for the task that increasingly preoccupied them: flight.

The boys first memory of flight was when their father brought home a toy helicopter, a contraption of wood and rubber bands, that they flew until it broke. But it was the news of the death, in August 1896, of Otto Lilienthal, the pioneer of glider flight, that resparked their interest in flight. In response, Wilbur did what he always did first: he read. Everything. When Orville recovered from a bout of typhoid, he joined his brother in scouring the libraries of Dayton. When these were exhausted, they wrote to the Smithsonian Institution asking for further reading – at the time, the Smithsonian was itself sponsoring expensive research into powered flight.

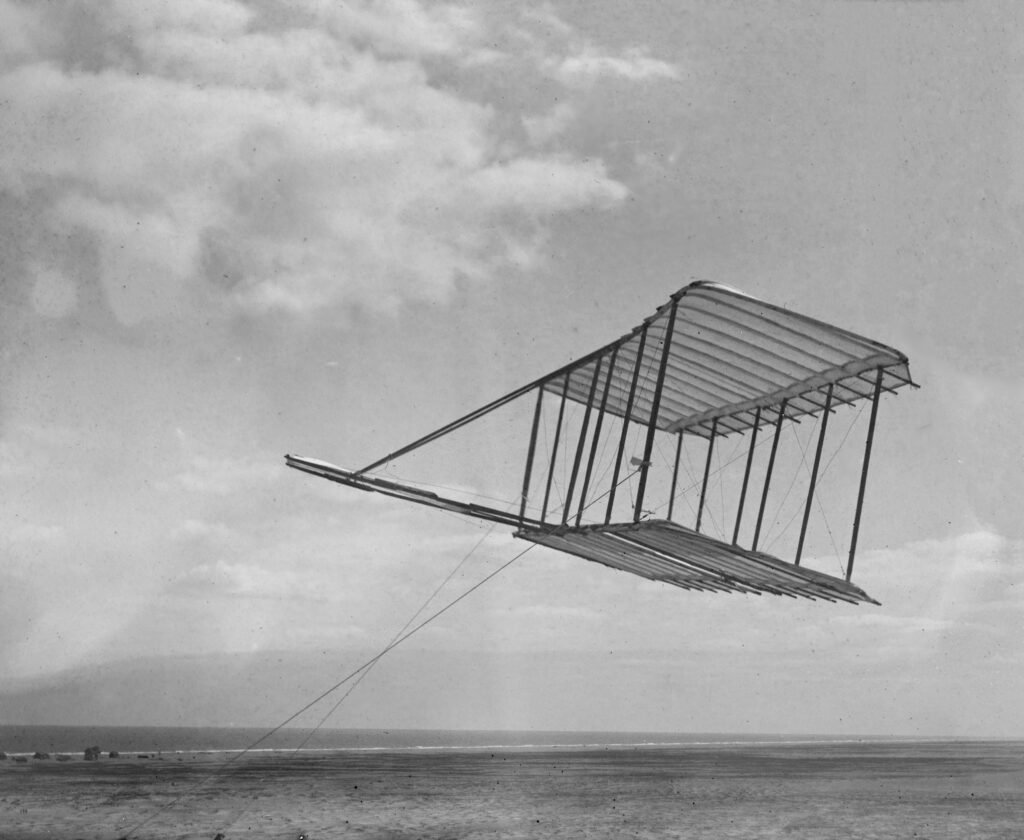

The Wright brothers were by no means the only people investigating flight: there were many inventors and teams working on how to fly. But what would set the brothers apart was the methodical way they broke down the problem and, in doing so, identified the key difficulty before flight could be achieved. The Wright brothers reasoned that there were three requirements for successful flight: a means of generating lift, some way of propelling the craft through the air and a system to direct and control the craft. All the other researchers were looking mainly at the first and second parts of the problem. The Wright brothers realised that it was the third part, the control system, that was least understood and most critical. After all, Otto Lilienthal, with his work on gliders, had demonstrated how wings could produce lift, and the burgeoning automobile industry was developing new, lighter and more powerful engines all the time. The real difficulty was control. This was where the brothers’ experience as cyclists was crucial. A cyclist, turning a corner, leans into the corner. They realised that the most effective way to turn a plane was for it to do the same, that it should bank in the direction it was turning (other researchers envisaged a system like a car, where the vehicle remains level while changing direction).

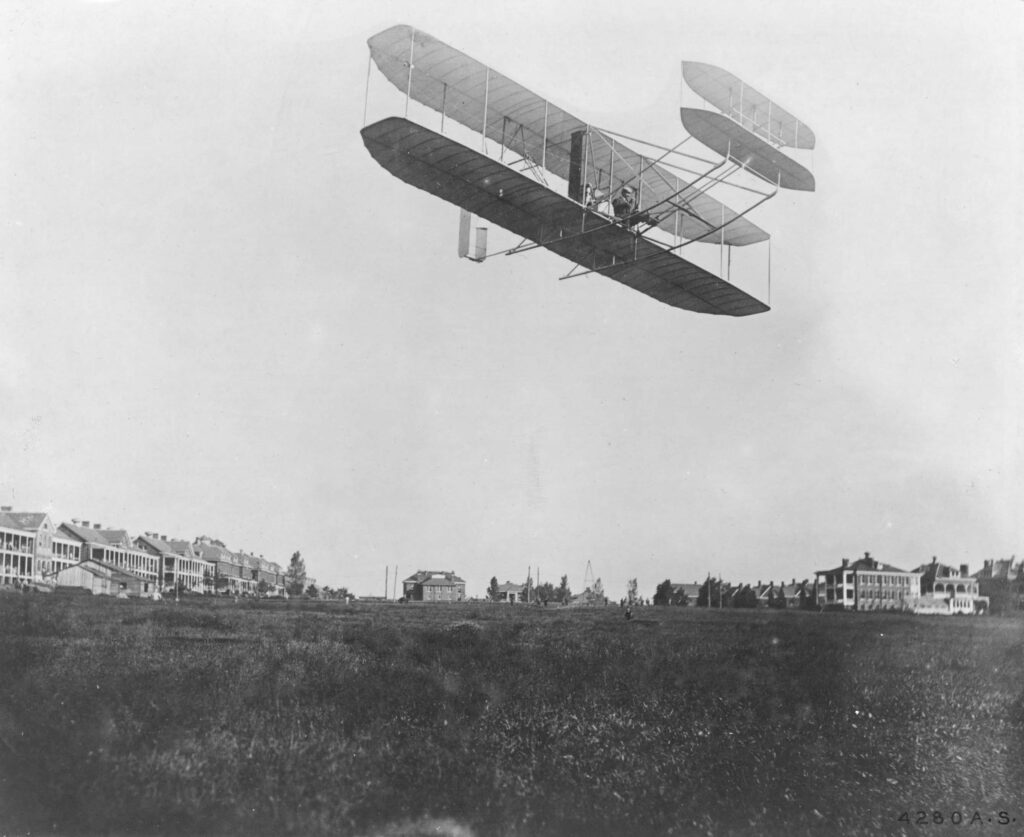

Starting with self-made gliders, the Wrights tested out their ideas for controlling a craft in flight, developing the system of three-axis control – roll (lateral motion), pitch (up and down) and yaw (side to side) – that underlies aircraft control systems to this day. Through three years testing at Kitty Hawk on the Atlantic Coast of America – a site chosen for its isolation, helpful winds and soft sand to cushion hard landings – the Wrights brought their craft towards the ideal of powered flight. In December 1903, they were ready. The first attempt, on 14 December, damaged the plane. But at 10:35 on 17 December 1903, Orville Wright took off, flying 120 feet (36m) and staying in the air for 12 seconds. Wilbur had the second go, going further, then Orville outdid him only for Wilbur’s final flight (852 feet in 59 seconds) to eclipse all three previous efforts. They had done it.

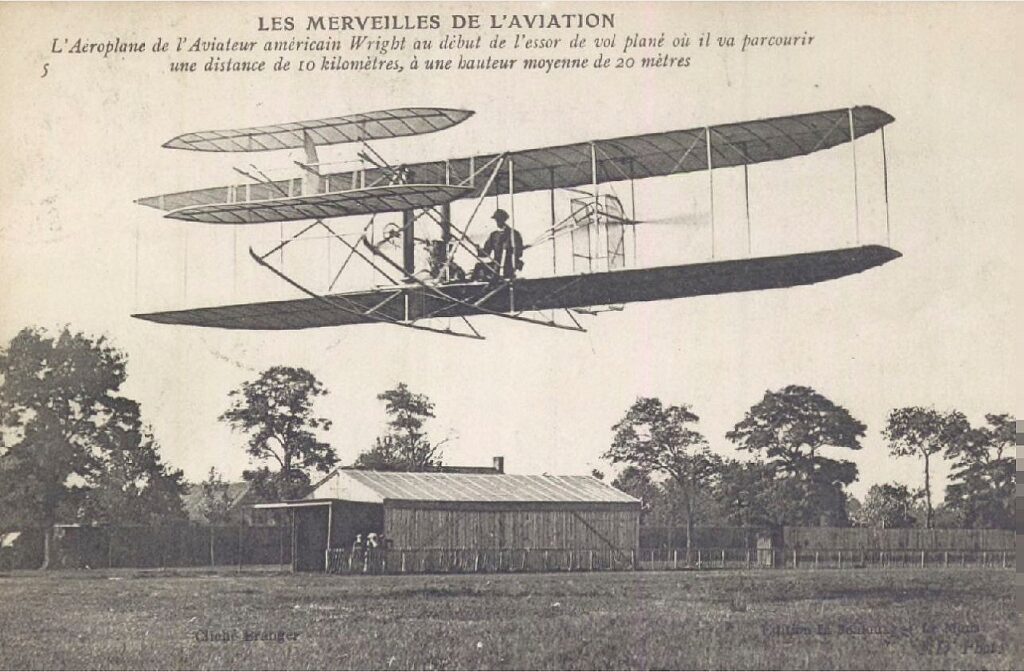

The press completely missed the story. The Dayton newspaper said the flights were so short the news wasn’t worth printing. Never men to court publicity, the Wrights weren’t too bothered. Besides, they wanted to perfect their airplane and they spent the next couple of years doing so. European aviators were sceptical of the rumours they were hearing about the Wright’s plane. All that would change in 1908, when Wilbur Wright began making public demonstration flights in France. All that they had heard about the Wright’s flyer was true – and more. Meanwhile, in America, Orville was demonstrating their plane to the US Army. The brothers, having funded their research out of their own pockets, needed to make money of their momentous invention.

The demonstration flights put an end to all doubts. The Wrights took off, flew circles and figure-8s, and landed, all while in total control of their planes. The two brothers from Dayton, Ohio, had done it. They had realised mankind’s second oldest dream. We could fly.

0 Comments