Adventures in Words: The Seven Basic Plots by Christopher Booker

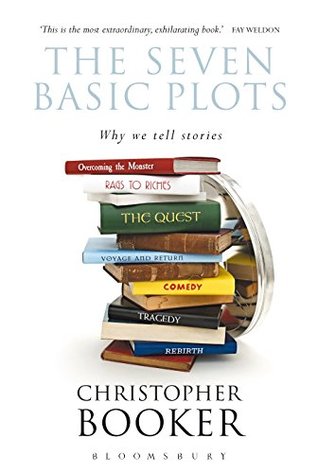

Christopher Booker doesn’t keep the reader in suspense: they’re right there, on the cover: Overcoming the Monster (Beowulf), Rags to Riches (Oliver Twist), The Quest (The Lord of the Rings), Voyage and Return (The Odyssey), Comedy (A Midsummer Night’s Dream), Tragedy (Hamlet) and Rebirth (A Christmas Carol). The stories in brackets are just a very few examples of the stories he quotes: one of the most impressive aspects of the book is that Booker seems to have read everything.

For the purposes of this review, I will take it as read that Booker makes his case: there really are only seven basic plots and all stories fall into these, although some incorporate more than one plot. For instance, The Lord of the Rings encompasses all seven of the plots. Instead, what I would like to consider is the why that Booker advances. Why do the stories that we tell, starting with the earliest stories known to us such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and continuing into the present day revolve around these seven basic plots? According to Booker, it is because they are shaped by the archetypes that, according to Carl Jung, sit deep in our unconscious, archetypes such as the shadow, the anima, the wise old man and so on, with the archetype of the self, the undivided whole adult human, being the gravitational centre around which the other archetypes revolve and to which they all aim to resolve.

According to Booker, the ideal story ends with its elements united and the Self realised, which is most often symbolised in stories by the hero marrying the heroine. This is the point and end of stories and, according to Booker, this is what gives them their unique power when told well.

I have some sympathy with this idea. But as sources of the fundamental meaning of life, Booker is asking purely human psychological constructs to take more weight than they can bear. Meaning, fundamentally, cannot be derived from the structures of our own psyches as, to use a metaphor, it is like blowing up a balloon and then expecting it to act as its own foundations. The sort of universal meaning Booker is talking about in his book cannot be located purely in the psychological structures of the mind, although these can be intimately connected to it, but has to be grounded in something deeper, wider, older and broader. Really, Booker is talking about God but seems unable or unwilling to acknowledge that.

So, curiously, the book suffers from something like the flaw that Booker ascribes to modern literature: an obsession with the the surface forms of things, the ego and its gratification at the expense of the deeper Self. The Seven Basic Plots likewise stops short before it reaches its destination, placing too much meaning in psychology while consciously or unconsciously avoiding the source of psychology, its ground and fountain.

However, the book remains a monumental body of work, deserving the highest accolade. I recommend it whole heartedly – and it will leave you wanting to read many more good books!

0 Comments