Book review: The Temple Tree by David Beaty

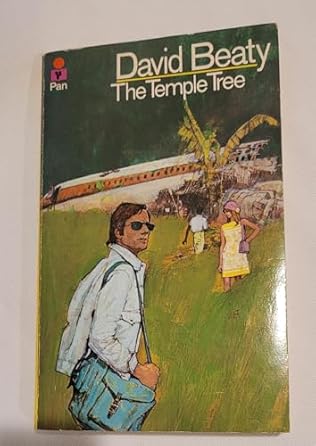

One of the joys of going away on holiday is browsing through the bookshelves of the house or hotel where we are staying. So, on our recent holiday, I was drawing my finger along the spines – sometimes the touch of a book can be as important as its appearance – when I stopped on a slim volume. Drawing it out, I saw a splendidly old-fashioned cover with the much missed Pan logo in the top right corner. But that’s not what made me read the book.

Turning it over to read the blurb, I discovered that the book was set in Ceylon, shortly before it became Sri Lanka on 22 May 1972. That the story involved an air-accident investigator trying to discover the reason a plane crashed on the approach to the country’s newest airport. And that the author, David Beaty, had been born and grew up in Ceylon himself.

Given that my father is Ceylonese (coming to Britain in 1960), and that I visited Sri Lanka for the first time in 1975 with my family, this was an intriguing prospect. Plus, there’s something salutary about reading the forgotten books of forgotten writers – after all, it’s a fate that will probably befall me. I suspect, for a writer, someone reading their books after their death is the equivalent of ten masses for the dead in shortening their time of waiting, so I do hope some of my books might be found, waiting in hope on a dusty shelf after I am dead, taken down, brushed off and read again, bringing ease to the dusty soul of this long-gone writer.

Having finished the book, I did some more research on David Beaty and while it’s true his novels are largely forgotten, it turns out that his research on air-traffic accidents was a crucial influence in ensuring that pilot psychology and crew resource management became essential elements of pilot training. So while his name might be receding, his influence endures.

On to the story. Plus points: I read it in four days, wanted to find out what happened next, and was satisfied with the ending. Negative points: it was rather disappointing in its evocation of post-colonial Ceylon. When we first arrived in Ceylon in 1975, I remember the overwhelming sensation of burgeoning life as we were driven from the airport into Colombo, the sense that one might spit the stone of a fruit out of the window of the car and see the budding tree bursting up out of the ground in the rear-view mirror. What’s more, the story is set during the monsoon season and there’s no real sense of the sweat and the grime, of the way that dirt collects under your fingernails even when you have four baths a day.

So, I am glad to have read the story and, David, I will say a prayer for the repose of your soul. But the story is likely to be left, quietly sitting on old bookshelves, the fading echo of a life’s work.

0 Comments