A German raised in Rome, Arminius nevertheless appeared a thorough-going Roman: fluent in Latin, an equestrian, a trusted auxiliary to the legions bent on conquering Germany. So when Arminius told the governor, Publius Quinctilius Varus, of a revolt, Varus had no hesitation in letting Arminius guide three legions into the depths of the forest. But Arminius had tricked him. Unknown to the Romans, Arminius was plotting against them and he had forged alliances among the German tribes. Having lured the legions far into enemy territory, Arminius slipped away. The attack, when it came in the Teutoborg Forest, was devastating. Strung out, the legions were annihilated, three imperial eagles captured, and Varus fell on his sword. The battle was one of the most decisive in history. Therafter, Rome made its frontier at the Rhine. However Arminius himself later fell victim to the jealousy of rival German nobles, who assassinated him in 21AD.

History

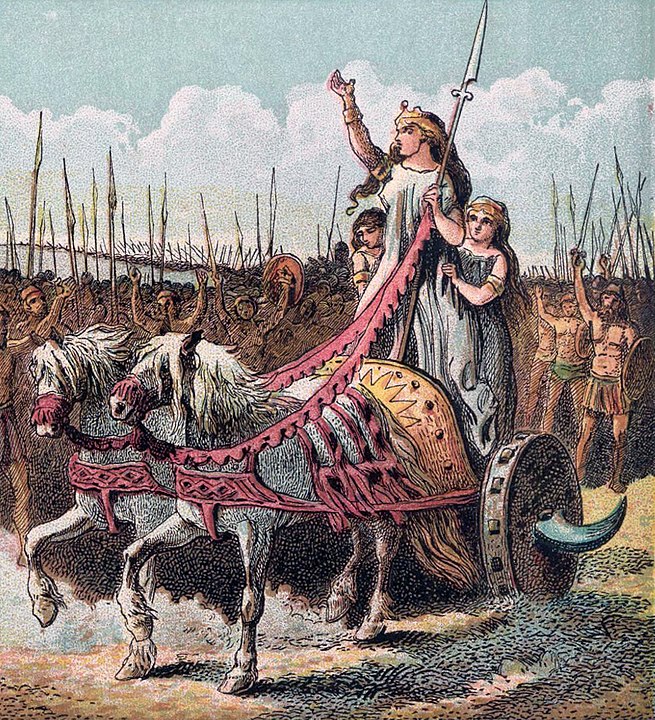

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Boudicca

Boudicca, queen of the Iceni tribe of East Anglia, saw her daughters raped when grasping Roman administrators attempted to steal her inheritance. She was flogged. Mistake. Boudicca led the British tribes in revolt, first attacking Colchester (Camulodunum). The Ninth Legion, hastening to put down the revolt, was destroyed. Gathering men as she went, Boudicca headed to London. When she arrived, she killed anyone who had stayed – 70,000 according to the Roman historian Tacitus – and burned what was left. Archaeologists can still see the red layer of Boudicca’s burning. Seeking battle with the Roman governor, Suetonius Paullinus, the queen of the Iceni marched north. Boudicca’s mistake. 10,000 Romans defeated Boudicca’s army of over 100,000. Boudicca herself either died from poison or illness.

Descartes’ Oven

On the night of 10 November 1619, the 23-year-old René Descartes, a soldier in the army of the Duke of Bavaria despite being a Frenchman, was stationed in Neuborg on the River Danube. It was bitterly cold and Descartes, a slight man sensitive to the cold, sought escape from the wind by sleeping in an oven. Later writers have questioned if he really meant an oven, arguing that he was referring to a room that was heated by an oven. After all, there aren’t that many ovens that a grown man can comfortably fit into. However, what happened next suggests that Descartes might have meant exactly what he said. For in this dark space, cut off from the rest of the world, he had a series of three dreams that proved formative of his future intellectual life. In these dreams, he believed a divine spirit had shown him the secret of analytical geometry – the Cartesian system we use today – as well as revealing that all that is true is joined together. Thus by finding one certain truth, he could go on to reveal all truth. It was not long after these visions that Descartes formulated the basis of his method of philosophy, the certainty that “I am, I exist”. As to the importance of the oven, Descartes, with his knowledge of Plato, would surely have seen its dark embrace as the modern restatement of the Cave from which Plato ascends to true knowledge of the eternal forms.

The Calculus Competition

In science, there’s no glory for second place. So when it came to claiming priority on the discovery of calculus, one of the key tools of modern mathematics, it’s little surprise that a dispute developed between Wilhelm Leibniz and Isaac Newton, both of whom had discovered methods of calculus independently, as to who had been first. But what is surprising is the dirty tricks both men stooped to. By the time the dispute broke into full force, in 1711, Newton was President of the Royal Society, the world’s oldest scientific institution. The Royal Society published an investigation into the question of who had invented calculus that roundly proclaimed Newton its originator and Leibniz a fraud. The impartiality of this report was somewhat compromised when it was revealed that Newton had written the conclusion. As for Leibniz, he was not above altering the dates of his letters and notes to back up his claim. Now it is generally accepted that both men independently invented calculus, although it is Leibniz’s notation that has become the standard way of doing calculus. Looking at the dispute is a reminder that two of the most intelligent men in history may still stoop to lies, evasions and slander to do down an intellectual rival: a playground spat between two superbrains.

The Extraordinary Adventures of Pêro da Covilhã

In 1487, King John II of Portugal dispatched Bartolomeu Dias to find the sea route round Africa and into the Indian Ocean. But King John didn’t just send ships: he sent spies too. In particular, Pêro da Covilhã, a low-born but multilingual adventurer. Covilhã, with letters of exchange to pay his way, made his way to Alexandria, the entry port to the Islamic world and then, passing himself off as a Muslim merchant, he made his way to Cairo and then on to Aden where he took ship on a dhow across the Indian Ocean, arriving in Calicut, India. Taking notes on the Indian Ocean spice trade, Covilhã then returned to Cairo where he met emissaries sent by John II, giving them his report. Now apparently bit by wonderlust, Covilhã explored Arabia, even entering Mecca and Medina in disguise as a Muslim pilgrim, before venturing across the Red Sea to Mount Sinai. From there, the indefatigable Covilhã headed to Ethiopia, the Christian kingdom in the heart of Africa and the probable source of the legends of Prester John. The ruler, Eskender, received Covilhã well but refused to let him leave. Thirty years later, a Portuguese embassy met their countryman, still living in the court of the kings of Ethiopia.

Taking Care of Business

Although William had made every effort to convince his magnates, his people and the wider world of Christendom of the justice of his case, yet the duke was old and wise enough to know that war was war, and even a war fought under God’s banner might turn against him. So, as part of his preparations, William nominated his eldest son, Robert Curthose, to succeed him as Duke of Normandy in the event of his death, and saw that Robert also signed William’s gifts to his new abbey. Curthose – a nickname – means short pants and suggests the difficult relationship between William and his elder son. Amid their other preparations, the Norman magnates spent much time setting their affairs in order. Everyone involved knew they were embarking on a do-or-die enterprise, and most of them sought to ensure they had settled outstanding disputes and matters of inheritance before they left.

Getting God On Side

Soon after he heard that Harold had been crowned king, William sent an embassy to Pope Alexander II in Rome, asking papal support for his projected invasion of England. Although the text has not survived, the case William made must have been persuasive: it no doubt rehearsed the familiar points of Edward’s promise of the throne and Harold’s perjury in swearing on holy relics to support William’s claim to the crown, and the pope soon decided in William’s favour. As mark of his support, Pope Alexander sent a banner with William’s returning messengers and instruction that England’s clergy should submit to William as king. For William, this was further proof that God was, indeed, on his side.

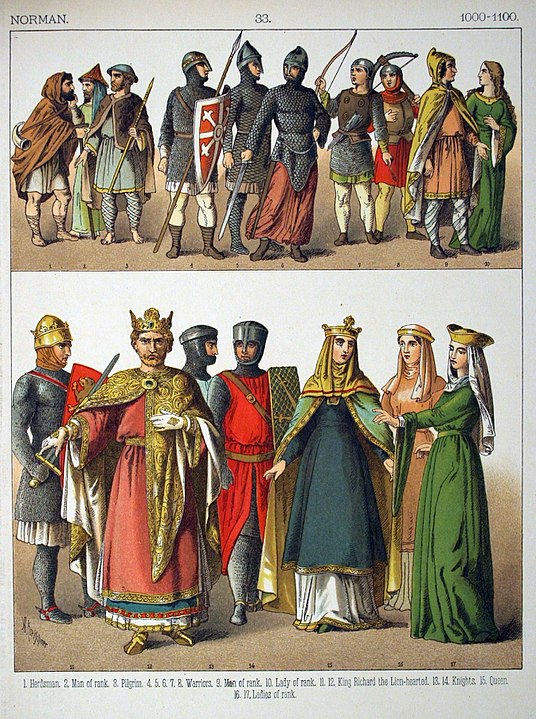

1066: The Men Who Would Be King

Harold, England’s most powerful man, had made himself king. But as Ealdred, Archbishop of York, placed the crown upon his head, Harold knew he was going to have to fight to keep the throne. There were no fixed rules of succession in 11th-century England. The new king should, ideally, be a blood relative of the dead ruler but might trumped claims of blood. And the only available blood relative to Edward was the young – no more than 13 – Edgar Ætheling, the grandson of Edmund Ironside. ‘Ætheling’ is an Old English title meaning someone who is throneworthy: Edgar was a suitable candidate for the throne.

But the crown did not rest upon blood alone. The reigning king might nominate his successor, and the sources indicate that Edward, on his death bed, did give his blessing to Harold as the man to succeed him. Unfortunately, Edward had also made such a promise to William, Duke of Normandy, and probably to Edgar Ætheling’s father too – and thus to Edgar himself.

Finally, there was the choice of the magnates of England. A king could not rule without their assent and, in choosing the new king, theirs were the most powerful voices. Assembled as they were, there can be no doubt that England’s magnates chose Harold as king; a choice made easier by the fact that Harold had cemented an alliance with the new earls of Northumbria and Mercia, Morcar and Eadwine, by marrying their sister, Ealdgyth.

The cast had assembled. It remained for the fatal drama to be played to its end.

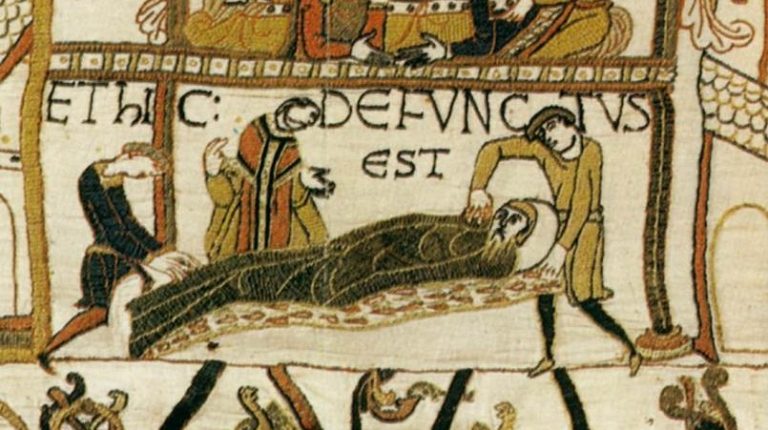

The Death Bed of Edward the Confessor

Did King Edward give the crown to Harold Godwinson, his most powerful earl, as he lay dying on 6 January 1066? The sources disagree, although most do aver that Edward did give rule of the kingdom into Harold’s hands. However, the life of Edward, commissioned by his queen, tells us who was with him on that fateful day: Edith herself, her brother Harold, the archbishop of Canterbury and the steward of the palace. The Bayeux Tapestry reproduces this scene. But what exactly did Edward say? Again, according to the Vita (Life) of Edward, the king commended the queen and the kingdom to Harold’s protection. Not exactly a ringing endorsement of Harold’s kingship – although admittedly the king was dying at the time. But, in England, the king’s wish did not determine his successor; in the end, that was a matter for the magnates of the country. And Harold had spent many years cultivating his contacts with them carefully. So it was no surprise that they chose Harold as king, and saw him crowned the same day as Edward died. The king was dead, long live the king. Or so they hoped.

The Scandalous Life and Death of Swein Godwinson, Harold’s elder brother

Swein Godwinson, the eldest son of Earl Godwin and Harold’s elder brother, led a tumultuous life. According to the man himself, he was the son, not of Earl Godwin but of King Cnut. However, his mother denied the claim vehemently. In 1046, Swein abducted Eadgifu, the abbess of Leominster, intending to marry her and claim the Leominster estates. When the king refused to agree to the marriage, Swein released Eadgifu, who returned to Leominster. But her abbey was disbanded, which suggests Eadgifu may not have been an entirely unwilling abductee. Swein fled to Flanders. In 1049, Swein returned, hoping to reclaim his territories, which had been split between Harold and a cousin, Beorn. Beorn eventually agreed to help Swein, but Swein ended up abducting Beorn too. The end for his cousin was worse than for the abbess: Swein murdered him. As a result, Swein was outlawed again. However, Earl Godwin engineered his forgiveness, but when the Godwins were exiled in 1051, Swein left the rest of the family to make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem and atone for his sins – these being so heinous that he went barefoot. But Swein, purged of his sin, died on the way back before he could sin again.