For nearly three hundred years, Mercia was the most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. When Ecgfrith, king of the Northumbrians, was killed in 685, Mercia filled the power vacuum, coming to dominate all the land south of the Humber, with only the kingdom of Wessex holding out against Mercian hegemony.

But of the three major Anglo-Saxon kingdoms – Northumbria, Wessex and Mercia – the history of Mercia is by far the worse attested, with most of what we know of its history coming from the pens of its enemies. Most notable among these is Bede, a proud Northumbrian, who despite the otherwise broad sweep of his History treats the Mercians pretty well only as antagonists.

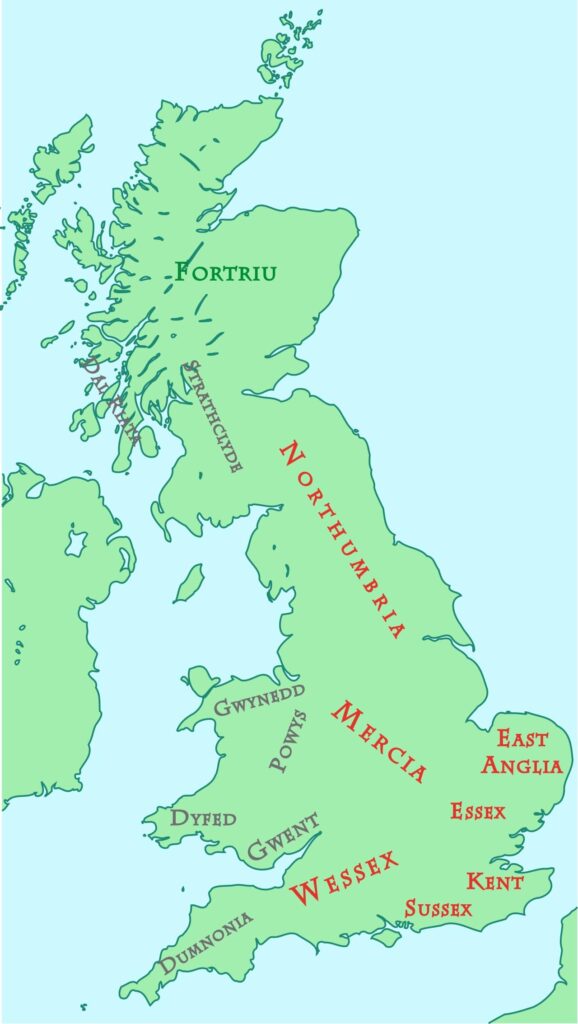

The name Mercia derives from Mierce, an Old English word meaning the ‘marches’ or ‘border people’ and that is what it was when first settled: the border kingdom between the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the south and east and the Britonnic kingdoms of the west and north. These people settled in the Midlands, following the river valleys into the heart of the country.

The king lists of the Mercians traced their lineage back to Icel, an Anglian prince who settled in Britain, giving the ruling family the name Iclingas. However, the first king to be reliably recorded is Penda, the great enemy of the kings of Northumbria, who killed two of them (Edwin and Oswald), as well as three kings of East Anglia. Penda was the last great pagan king of the Anglo-Saxons and when he fell in battle with Oswiu, Oswald’s brother and successor as king of Northumbria, the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity was assured.

Mercia and Northumbria continued to struggle for dominance until, with the death of King Ecgfrith in 685, Mercian supremacy was assured. It reached its height during the reign of King Offa (757 – 796), when Mercian power encompassed the whole country and Offa could deal, almost as an equal, with no less a king than Charlemagne. The power Offa wielded is given earthen form in the vast labour required to build Offa’s Dyke.

However, Mercian power declined after Offa’s death, and was then dealt a terminal blow with the arrival of the Great Heathen Army in 868. The Vikings deposed Burgred, king of the Mercians, in 874 and installed a puppet king in his place. Following the victory of Alfred of Wessex over the Vikings, Mercia was divided, its north eastern half becoming part of the Danelaw, its south western portion being ruled by an alderman owing fealty to Alfred. Even following the reconquest of the Danelaw by Alfred’s children and grandson, Mercia remained part of the expanding kingdom of the men who had come to see themselves as not just the kings of the West Saxons but the kings of the English.