This is the text of an article that I wrote for the now defunct Catholic Life magazine. I hope you like it.

Although the retreat from the world and its buzzing, tempting distractions was present in Christianity even before Christianity existed as a separate religion – think of John the Baptist’s voice crying in the wilderness and Christ’s withdrawal into the desert for forty days of fasting following His baptism by John – yet the main foundations of Christian monasticism and eremiticism were not laid for some four centuries. Early Christians seem to have felt little need for the ‘white martyrdom’ of withdrawal when the ‘red martyrdom’ of public and prolonged execution was easily available. But with toleration of the Church granted by the Edict of Milan in 313 and its subsequent favoured status as Imperial religion, the lions were no longer an option. Other paths to Christ had to be found; perhaps less direct but, usually, less bloody.

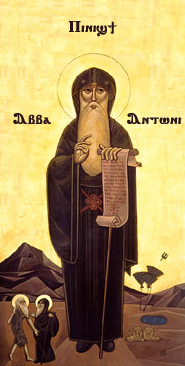

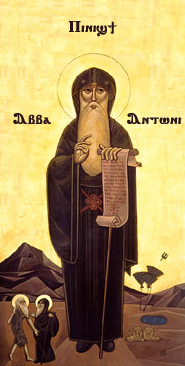

This path had already been blazed by St Anthony, who set off into the Egyptian desert in 270 AD. As a twenty-year-old man, Anthony had heard the Gospel read in church: “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell all that thou hast and give to the poor, and come and follow Me.” Anthony did. He was reasonably well-off, but he gave away what he had, save what was necessary to ensure the upkeep of his sister, and went off into the desert, striving in solitude against the temptations and attacks of demons for some twenty years. Only after that did he begin to see people again, and what started off as a trickle quickly grew into a flood, with hundreds of men living as hermits near him and crowds coming from nearby towns to see him. And thus Anthony lived the paradox of solitude: so often those who flee into aloneness are pursued relentlessly by those who would no more live alone than they would cut out their tongues.

But how do you disappear into the solitude of the desert when you live in a land where drowning by rain is a greater danger than dying of thirst? That was the problem faced by the first monks of Ireland. Never having been part of the Roman Empire, the human geography of the island was completely unlike the Romanised parts of Europe. There was hardly anything that could be called a town, let alone a city. The people were tribal and diffused, and thus the early Christian monasteries had no rivals as centres of learning and civilization. So monasteries grew large, and noisy, and oftentimes less prayerful. From them, men withdrew into the wilderness that Ireland did provide, a wildness of wind and water, physically cut off from human contact by the sea: islands.

Pilgrimage became one of the key features of Irish Christianity. Putting their trust in God and their goods in boats so small they wouldn’t even qualify as a dinghy today, groups of monks or even men alone would set off. Some, no doubt, foundered. Others founded new communities, or found the solitude they were searching for.

On Skellig Michael, a pinnacle of rock jutting out of the Atlantic Ocean eight miles west of Kerry, are the remnants of one such community: six huts, made of slate and looking like nothing so much as stone beehives are perched 714 feet above the sea. It’s hard to tell what is more overwhelming here, the sea or the sky. The Vikings, though, made their own unique bid to be more overwhelming than the elements by repeatedly pillaging the monastery. However, the monks endured and, according to some accounts, had their ultimate revenge on the Viking raiders by baptising the future king of Norway, Olaf Tryggvason. The island is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

But even in this extraordinarily remote spot, there can still be a desire to withdraw into even greater solitude. This is illustrated perfectly on Skelling Michael by the even more remote hermitage, perched atop the south western peak of the island.

The Cambrai Homily, the earliest known Irish sermon, dating from the seventh or early eighth centuries, reveals quite precisely how these monks at the world’s end understood their calling:

Precious in the eyes of God:

The white martyrdom of exile

The green martyrdom of the hermit

The red martyrdom of sacrifice.

Combined with pilgrimage, it was a transforming and transformative package. But sometimes, relocation was forced. St Columba was exiled from Ireland for his involvement in a pitched battle over the ownership of a psalter – books were literally a matter of life and death then. He landed on the island of Iona in 563 and founded there one of the most renowned monasteries of the period. From Iona, missionaries spread out, taking the Gospel around the coast of the British Isles and on, into those parts of northern Europe that had lain beyond the boundaries of the Roman Empire.

Perhaps the best example of this skipping-stone effect is provided by St Aidan. A monk of Iona, he was sent to the kingdom of Northumbria at the request of King Oswald to convert his heathen people. In the early days of Aidan’s mission, the king had to translate the monk’s Irish into the local language, but Aidan and his companions soon learned the language that would become English and set about creating a civilization. The luminous fruit of the monks’ labours are the Lindisfarne Gospels, on show in the British Museum but present in facsimile, physical and virtual, on Lindisfarne at the Lindisfarne Centre (01289 389004, www.lindisfarne-centre.com). The Lindisfarne Gospels themselves had been moved before finding their final home in the British Museum, hurriedly carried into hiding when the Vikings came calling to Lindisfarne too.

Even more precious to the refugee monks of Lindisfarne than their books was the relics of the greatest saint of Holy Island, Cuthbert. They carried the saint’s body with them on a meandering journey across Northumbria until he was finally settled in Durham Cathedral, where he remains to this day. But one suspects that Cuthbert might have preferred that his mortal remains stay on the little island, within sight of Lindisfarne, to which he in turn withdrew to escape his fame and focus more clearly on God. His fame was very great though, and for good reason. Soldier, visionary, missionary, ecologist, orator and ascetic, Cuthbert was all of these things, but in an era when miracle nestled up against the common place, Cuthbert’s reputation as a worker of wonders was unequalled. It’s hard now to tell how much credence to place on reports, but Bede, writing in a time when there were still eyewitnesses to Cuthbert’s deeds alive, reports him calming storms, stopping a house burning by prayer, healing and expelling demons, even turning water into wine. And when, on exhumation 11 years after death, his body was found incorrupt, his reputation as a wonder worker grew further.

The Farne Islands, to which Cuthbert escaped for eight years of relative peace, are still wild and uninhabited, save for the hundreds of thousands of sea birds who nest there over the summer, and the National Trust wardens who monitor them. St Cuthbert, who passed laws protecting Eider ducks and other nesting sea birds that were probably the first piece of wildlife conservation legislation in the world, would be pleased.

The Farne Islands, Lindisfarne, Iona and Skellig Michael are all, to varying degrees accessible today. But even the easiest journey, across the causeway to Lindisfarne, still takes modern-day pilgrims away from the bustle of the mainland and to places where different rhythms prevail.

Over the last few decades, more people have been called to the eremitical life, to such an extent that the Code of Canon Law promulgated in 1983 makes provision for them. It is perhaps not surprising that in a world that daily becomes noisier and busier, the song of solitude is being heard as it has not been heard for centuries.