The Dawn of the Age of Discovery

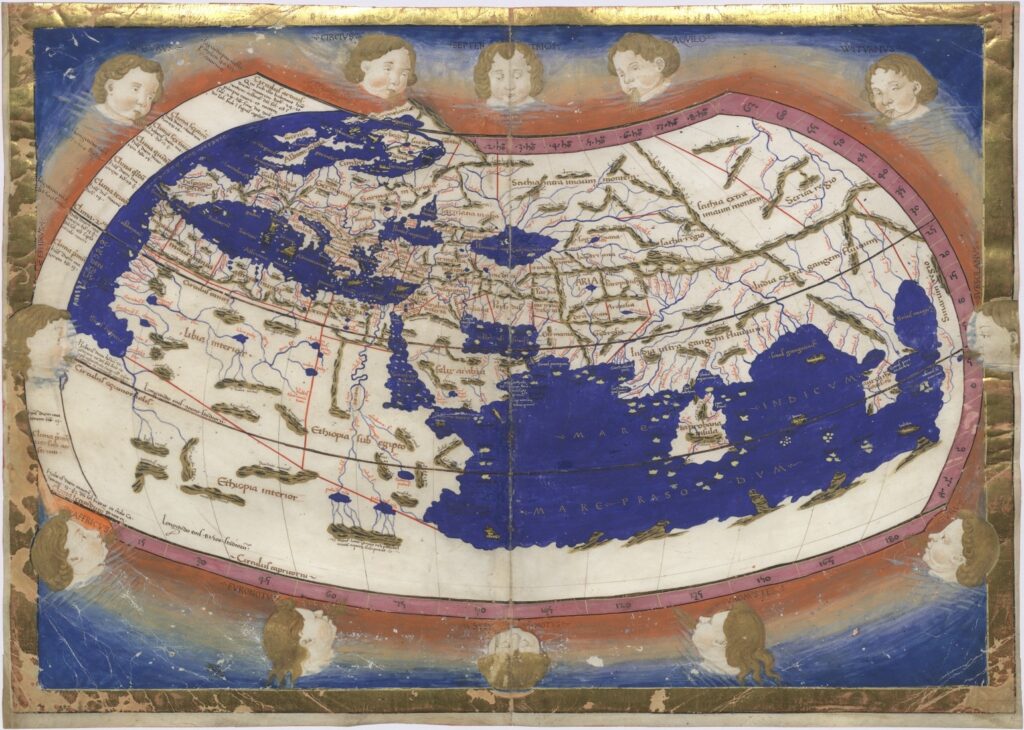

In the early 15th century, Portugal was a poor country stuck on the edge of the world, hundreds of miles from anything. The Mediterranean remained what its name proclaimed it to be: the centre of the world. It was via maritime trade routes running across the Mediterranean that the hugely lucrative spice trade with the east ran. The Italian maritime republics, Venice and Genoa, had sewn up the trade in luxury goods from the east, establishing fiercely defended monopolies. All the Portuguese had was the Ocean, the endless World Ocean that, according to the geographer Ptolemy, enclosed all the lands of the world, possibly continuing without end.

What seemed set to lock out the Portuguese from this lucrative trade was the fact that, according to Ptolemy, the Indian Ocean was landlocked. The most eminent authority of antiquity averred that the Portuguese might sail to the ends of the world and still never gain access to the ports trading pepper and gold and silk. They were stuck forever with only Ocean as their western boundary.

But through a concerted, generation spanning effort that required the whole-hearted support of the Portuguese crown, this small, poor nation – so poor that that at the start of the great enterprise the King of Portugal was too poor to mint gold coins – fundamentally changed the nature of the world, giving birth to the global, interconnected world in which we live today.

To do this, the Portuguese made use of a number of discoveries, some indigenous, others borrowed. Fundamental among these were compasses, imported from China via Arab traders, and the caravel, developed in Portugal, the revolutionary ship design that opened up the Atlantic Ocean to Portuguese explorers by allowing sailors to sail windward by beating (tacking backwards and forwards at an angle to the prevailing oncoming wind). Caravels were fast and manoeuvrable, with the triangular lateen sails allowing it to sail windward while the square-rigged sails gave it speed before the wind.

0 Comments