Adventures with Words: The Mask of Apollo by Mary Renault

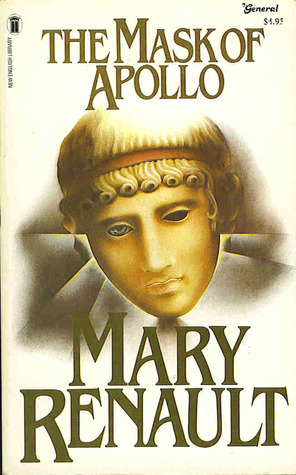

The Mask of Apollo by Mary Renault

“All tragedies deal with fated meetings; how else could there be a play? Fate deals its stroke; sorrow is purged, or turned to rejoicing; there is death, or triumph; there has been a meeting, and a change. No one will ever make a tragedy – and that is as well, for one could not bear it – whose grief is that the principals never met.”

I first read ‘The Mask of Apoll’o when I was in my teens and the book’s last paragraph, and particularly its last sentence, has haunted me ever since. Now, decades later, I reread the story that I might remember what lead up to that last sentence and it is indeed as devastating a story as that final sentence demands. For I read the book because at the time I was also reading the dialogues of Plato and ‘The Mask of Apollo’ tells the story, through the eyes of the actor, Nikeratos, of Plato’s attempt to put his theories of statecraft and the philosopher king into practice by teaching Dionysus, the tyrant (in the ancient Greek sense of a king relatively untrammeled by the restraint of law) of Syracuse in Sicily, the principles and ethics of philosophy, and of Plato’s brilliant pupil, Dion, a Syracusan aristocrat who could have seized the throne for himself.

The decades had rubbed away Renault’s brilliant depiction of the realities, at least so far as we can reimagine them, of Greek theatre, but it had not removed the tragedy that hangs over the story. The first-order tragedy is a man, Dion, by temperament and training perfectly suited to be the philosopher king of Syracuse who turns down the chance precisely because he is a man of pre-eminent virtue and will not usurp a throne that is not, quite, rightfully his. This is coupled with the tragedy of Dionysus II, oscillating between his good and evil selves, with Plato as the physical presence of his decaying conscience.

This is a thorough examination of the workings out of political philosophy in reality and is thoroughly absorbing, highlighting all the best features of historical fiction in its bringing to life of an ancient culture, the events within that culture and the people who lived through those events.

But it is final chapters of the book, after Plato’s death, that bring it to a higher level of tragedy. Nikeratos travels to Macedonia with his theatre company and there meets a young prince in his early teens but already almost god-like in his charisma, a fire seeking fuel for its burning. The young Alexander has a tutor, and no ordinary tutor for his teacher is no other than Aristotle. But the fire in Alexander’s soul is, Renault implies, searching for a different fuel. Alexander burns through the world seeking it, but what he is looking for in the world has already left it, broken at the failure of his attempts to foster a perfect kingdom. Hence the final, gutwrenching, sentence of the book.

0 Comments