‘In Northumberland alone, both heaven and earth are seen.’ So wrote the historian GM Trevelyan and, if hell is other people, then the reason for this quickly becomes clear. There’s no one else around. Northumberland’s 1,936 square miles are the most sparsely populated in England, and less than 2,000 people live within the 405 square miles of the Northumberland National Park. If that doesn’t give you sufficient air to breathe, the Cheviot Hills are the least visited part of the least visited national park in England. Is that space enough?

So, it’s empty, but is that it? Is there any there, there? Well, if adjectives like solitary, windswept and bleak fill you with anticipation rather than a desire for a Martini and decent reception for your mobile phone, you may just have found your earthly paradise. After all, in these crowded islands, a place where you can walk all day and not see another soul is precious.

Now, the normal practice in a travel article would be to write about the geology (worn-down volcanoes and built-up silt), archaeology (hunters, gatherers, hill forts) and history (the Romans came, looked around and went back behind the Wall) of the area, but while all of this is valuable it’s not the best way to convey an idea of the Cheviots. For this is a land of impressions, of cloud shapes cast upon hills of green and brown, and its essence lies in the waving flags of cotton grass, the brief blaze of heather and the fleeting glory of hay meadows. It’s a paradox of place that these smooth-backed hills leave fragmentary images in the memory: tangles of wool dangling from hollowed-out gorse bushes like tattered beards; flowers small and bright as stars speckling the grass.

But before we climb up to the high places, let’s look around. The hills are demarcated by heather and bracken, plantations and moors, but most of all by dry stone walls. These are so much a feature of the environment that it’s easy to overlook what an extraordinary exercise in hard labour and applied topology they represent. The illiterate labourers who made them would be worthy of a chair in mathematics at Cambridge University today, such was their ability to add irregular, multi-sided objects together and make a smooth-sided wall.

Of course, the other great shapers of the landscape are the self-powered mowers that bleat. Sheep speckle the hillsides and lonely walks (and every walk in the Cheviots is lonely) produce curious musings about the creatures. Venture up on to Housey Crags on the way to the distinctive round top of Hedgehope and the large amount of sheep droppings reveal that the beasts must have a desire for romantic vistas and breezy landscapes to match the most athletic of the Romantic poets. It can’t be the grass, there’s bugger all to be found on these exposed rocks.

Mind you, sheep aren’t the only ones to frequent the hill tops. Our Iron Age ancestors studded the area with their dwellings, but we still don’t know why they switched to building hill forts around 500BC, nor the reason for constructing them in such high and exposed positions – defence, prestige, both? – but one thing quickly becomes apparent when labouring to the top of Yeavering Bell or Brough Law: they must have had thighs like tree trunks.

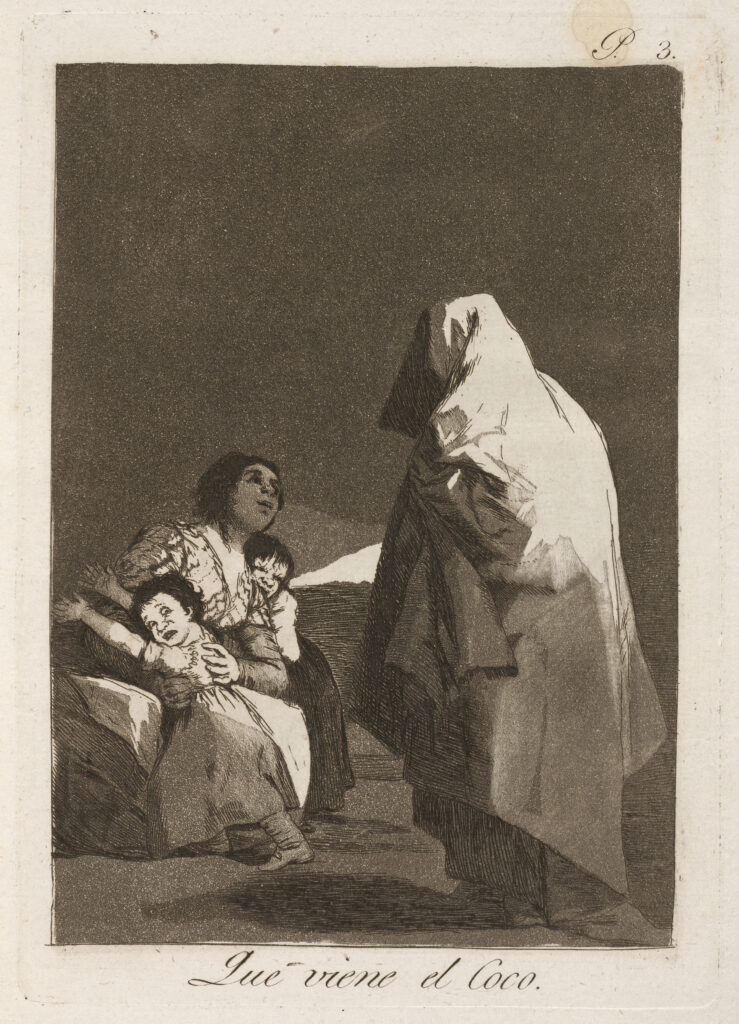

That walk to the hill fort on Yeavering Bell in particular produces musings on the fate of Ozymandias (‘Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair’), for the climb begins at the site of Ad Gefrin, the palace of King Edwin that Bede chronicled in his history. It’s now a field. And sheep graze where the chieftain of Yeavering Bell once sat, lord of all he surveyed. But then, maybe transience came as little surprise to that long-ago king. For even a high king’s orders must have sounded different when uttered in the heights. Try it yourself. Try speaking out loud when you’re alone on the hills. Your voice will sound different, like breath blown by the wind: quiet, fleeting, mortal.

Other, different, voices sound more at home here. The hay meadows of Barrowburn are heavy with the buzzing of bumblebees, while the whale backed ridge of The Cheviot – the singular hill from which the range takes its name – comes alive in summer with the song of the meadow pipit, singing as it labours upwards and then falls, trilling, away, or the skylark, diminishing to a black dot against the clouds, its voice filling the empty, windy wastes with bubbling, trilling, streams of music. But most of all, the high hills are the range of the ravens. If you’re lucky you might see a pair, riding the rolling air, or hear their extraordinary call, like two pieces of hollow wood being clapped together. The lower reaches are where their more voluble cousins, the rooks and the crows, abide, in gossiping, hurrying flocks, looking rather like the crowd at a Sisters of Mercy gig.

The world has changed a great deal since people first came to the Cheviots. Then the Wild Wood was an encroaching threat on the scattered pockets of humanity, now it’s reduced to a few preserved islands in the sea of humanity. The hills stand largely bare in a sombre, grave landscape of muted greens and browns. They don’t invite you. They don’t even notice you. But should the press of people become too great, the endless procession of anonymous faces too numbing, then come here, stand upon a cloud-flecked hill and hear the voice of the wind. You’ll be the only one listening.