Theodoric (454 – 30 August 526), known as the Great, led his people, the Ostro (‘eastern’) Goths into Italy in 489, defeating Odoacer, the first barbarian king in battle and beseiging him for three years in Ravenna. When Theodoric could not take the city, he negotiated a shared rule and entered the city. All seemed cordial at first but then, ten days later, Theodoric personally murdered Odoacer and his men killed all Odoacer’s family. So one Barbarian Hall of Famer met his suitably barbaric end at the sword of another. Nevertheless, after this bloody beginning, Theodoric strove to maintain peace for the rest of his rule, trying to persuade his people to treat their Roman subjects well. His remarkable mausoleum still stands in Ravenna.

Blog

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Odoacer

Odoacer (c.433 – 15 March 493) deposed the last emperor of the western Roman Empire and became the first barbarian king of Italy. Like many barbarian warriors, Odoacer had found employment with the remnants of the Roman army under the command of Orestes, the ‘master of soldiers’. But when Orestes appointed his son, Romulus Augustulus, emperor and refused reward for his men, Odoacer killed Orestes and deposed Romulus. But so powerless had the emperor become that Odoacer let Romulus live, giving him a pension and a long retirement with his relatives. The Roman Empire in the West was finished: the barbarians had won.

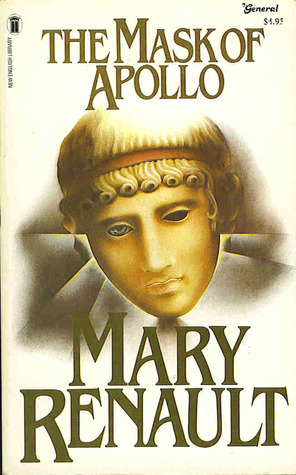

Adventures with Words: The Mask of Apollo by Mary Renault

The Mask of Apollo by Mary Renault

“All tragedies deal with fated meetings; how else could there be a play? Fate deals its stroke; sorrow is purged, or turned to rejoicing; there is death, or triumph; there has been a meeting, and a change. No one will ever make a tragedy – and that is as well, for one could not bear it – whose grief is that the principals never met.”

I first read ‘The Mask of Apoll’o when I was in my teens and the book’s last paragraph, and particularly its last sentence, has haunted me ever since. Now, decades later, I reread the story that I might remember what lead up to that last sentence and it is indeed as devastating a story as that final sentence demands. For I read the book because at the time I was also reading the dialogues of Plato and ‘The Mask of Apollo’ tells the story, through the eyes of the actor, Nikeratos, of Plato’s attempt to put his theories of statecraft and the philosopher king into practice by teaching Dionysus, the tyrant (in the ancient Greek sense of a king relatively untrammeled by the restraint of law) of Syracuse in Sicily, the principles and ethics of philosophy, and of Plato’s brilliant pupil, Dion, a Syracusan aristocrat who could have seized the throne for himself.

The decades had rubbed away Renault’s brilliant depiction of the realities, at least so far as we can reimagine them, of Greek theatre, but it had not removed the tragedy that hangs over the story. The first-order tragedy is a man, Dion, by temperament and training perfectly suited to be the philosopher king of Syracuse who turns down the chance precisely because he is a man of pre-eminent virtue and will not usurp a throne that is not, quite, rightfully his. This is coupled with the tragedy of Dionysus II, oscillating between his good and evil selves, with Plato as the physical presence of his decaying conscience.

This is a thorough examination of the workings out of political philosophy in reality and is thoroughly absorbing, highlighting all the best features of historical fiction in its bringing to life of an ancient culture, the events within that culture and the people who lived through those events.

But it is final chapters of the book, after Plato’s death, that bring it to a higher level of tragedy. Nikeratos travels to Macedonia with his theatre company and there meets a young prince in his early teens but already almost god-like in his charisma, a fire seeking fuel for its burning. The young Alexander has a tutor, and no ordinary tutor for his teacher is no other than Aristotle. But the fire in Alexander’s soul is, Renault implies, searching for a different fuel. Alexander burns through the world seeking it, but what he is looking for in the world has already left it, broken at the failure of his attempts to foster a perfect kingdom. Hence the final, gutwrenching, sentence of the book.

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Vercingetorix

Julius Caesar had all but completed the conquest of Gaul when Vercingetorix, leader of the Averni, led an uprising in 52 BC. He defeated Caesar at the Battle of Gergovia but was later forced to retreat to his stronghold at Alesia. When attempts to lift the siege failed, Vercingetorix surrendered to Caesar, so that he could save as many of his own men as possible. Julius, with his eye on publicity, kept Vercingetorix captive for five years so that he could appear in Caesar’s triumph in Rome. Having served to bolster Caesar’s fame, Vercingetorix was strangled a few days later.

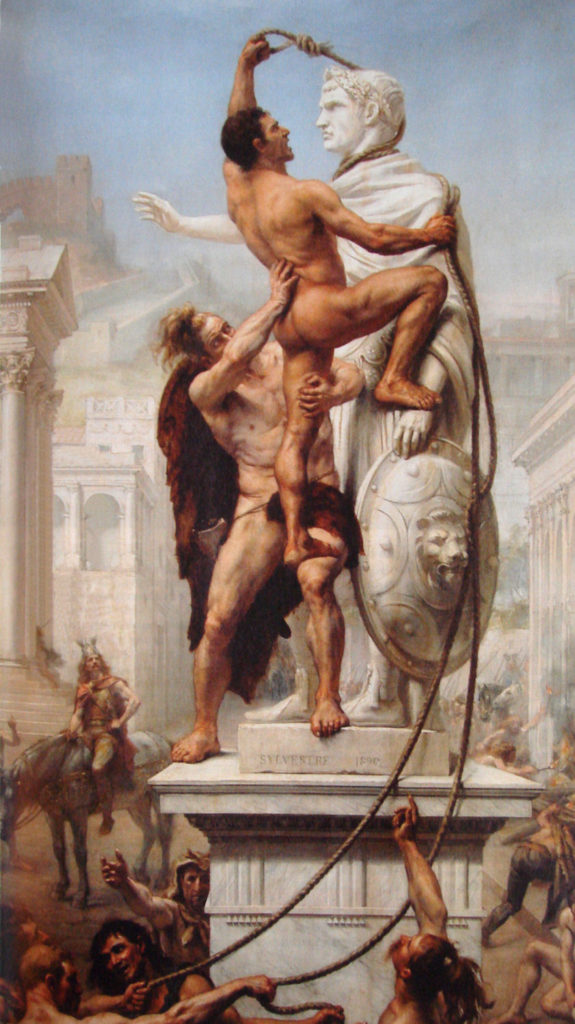

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Brennus

Brennus (born 4th century BC, died after 387 BC) did what it would take barbarian warlords nearly another 800 years to repeat: take Rome. A Roman army met the Gauls eleven miles north of the city in July 387 BC – and was annhilated. The panicked citizens fled, leaving only the Capitoline Hill defended, and the Gauls sacked Rome. Brennus and his men beseiged the Capitoline for seven months: the defenders were only alerted to one night-time assault by the honking of the sacred geese in the temple of Juno. In the end, the Romans bought Brennus off with a thousand pounds of gold but when the Romans weighed out the gold to save their city, they found the wily barbarian had brought fixed weights to the weighing and Brennus threw his own sword onto the scales, famously saying, “Vae victis!” (“Woe to the conquered!”).

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Clovis

The reign of Clovis, the first king of the Franks, marks a decisive shift from barbarian warlords fighting over the last pickings of the Roman Empire to kings ruling new kingdoms. The father of Clovis, Childeric, was a pagan: his tomb contained a gold bull’s head and three hundred garnet-set gold bees. But Clovis, under the influence of his wife, Clotilde, converted to Catholicism, thus setting the religious template for his people. By this time, Clovis had already conquered and assimilated the smaller Frankish kingdoms and, in 486, he defeated the last representative of the waning Imperial power at the Battle of Soissons. Clovis was king but he had no interest in proclaiming himself emperor. Europe, with its patchwork of competing nations, was struggling towards birth.

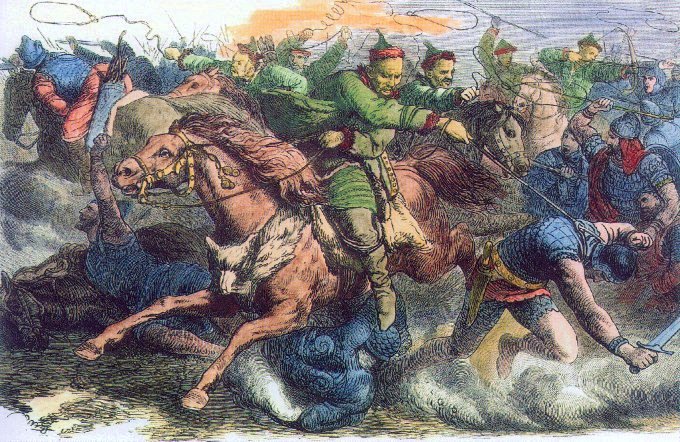

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Attila the Hun

The most famous barbarian of them all never took Rome. First, Attila attacked the Eastern Empire, forcing it to pay annual tribute of 2,100lbs of gold. Having extracted all he could from the Eastern Empire, Attila needed a pretext to attack the Western Empire. In 450, the emperor’s sister provided it. Honoria had had an affair with her estate manager and become pregnant. The manager was executed and Honoria married off to an elderly senator. Determined to escape, Honoria sent a letter and her ring to Attila, asking his aid. Attila demanded half the Western Empire as dowry and invaded. The Roman general, Aetius, met Attila in battle at the Catalaunian Plains and forced him to withdraw. The Hun was beaten. But not defeated. In 452, Attila attacked Italy. An embassy, including Pope Leo I, went to meet him and, somehow, persuaded him to withdraw. In the end it was not battle that defeated Attila but his own body: taking yet another wife, he retired to bed after drinking an inordinate amount, only to be found dead the next morning, next to his hysterical bride.

The Ultimate Accolade for a Writer

This was said to me yesterday.

“I knew I recognised your name. I’ve got your book in my toilet.”

I can now die content!

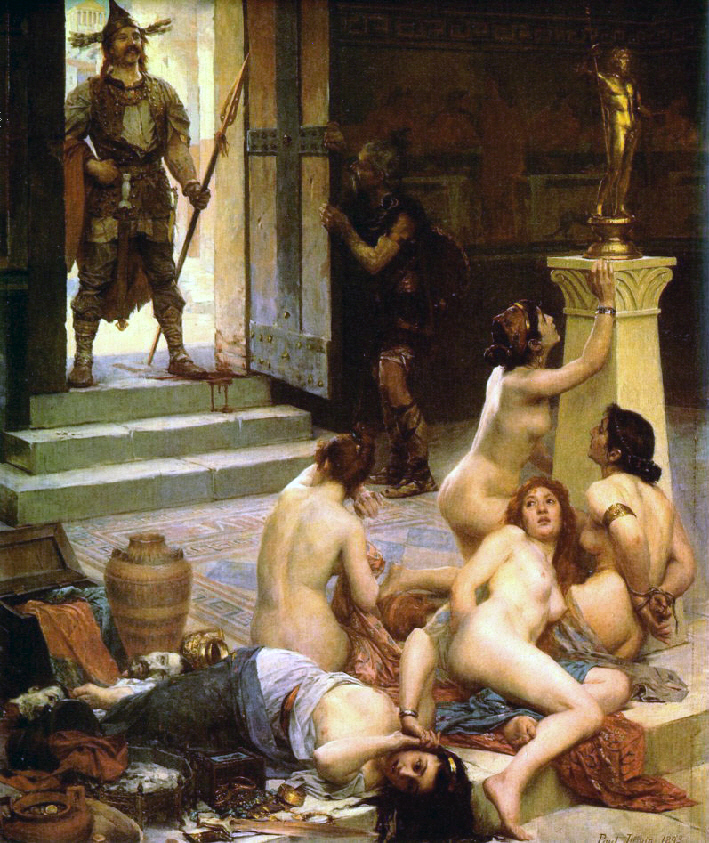

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Alaric

Alaric was the barbarian who finally did what others had tried to do for centuries: sack Rome. When Emperor Honorius, holed up in Ravenna and protected by the surrounding marshes, refused to negotiate, Alaric and his Goths turned on Rome. They’d already beseiged it twice in an effort to get the Romans to pay up. On the night of 23/24 August 410, the Salarian Gate was opened to Alaric. For three days, the Goths plundered the Eternal City, although with more restraint than usual: this was more asset stripping than rape and looting. The city had not been taken by an enemy for nearly 800 years. The myth of Roman invincibility irrevocably broken, Alaric headed south, aiming for Africa, but died of natural causes.

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Arminius

A German raised in Rome, Arminius nevertheless appeared a thorough-going Roman: fluent in Latin, an equestrian, a trusted auxiliary to the legions bent on conquering Germany. So when Arminius told the governor, Publius Quinctilius Varus, of a revolt, Varus had no hesitation in letting Arminius guide three legions into the depths of the forest. But Arminius had tricked him. Unknown to the Romans, Arminius was plotting against them and he had forged alliances among the German tribes. Having lured the legions far into enemy territory, Arminius slipped away. The attack, when it came in the Teutoborg Forest, was devastating. Strung out, the legions were annihilated, three imperial eagles captured, and Varus fell on his sword. The battle was one of the most decisive in history. Therafter, Rome made its frontier at the Rhine. However Arminius himself later fell victim to the jealousy of rival German nobles, who assassinated him in 21AD.