Julius Caesar had all but completed the conquest of Gaul when Vercingetorix, leader of the Averni, led an uprising in 52 BC. He defeated Caesar at the Battle of Gergovia but was later forced to retreat to his stronghold at Alesia. When attempts to lift the siege failed, Vercingetorix surrendered to Caesar, so that he could save as many of his own men as possible. Julius, with his eye on publicity, kept Vercingetorix captive for five years so that he could appear in Caesar’s triumph in Rome. Having served to bolster Caesar’s fame, Vercingetorix was strangled a few days later.

Blog

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Brennus

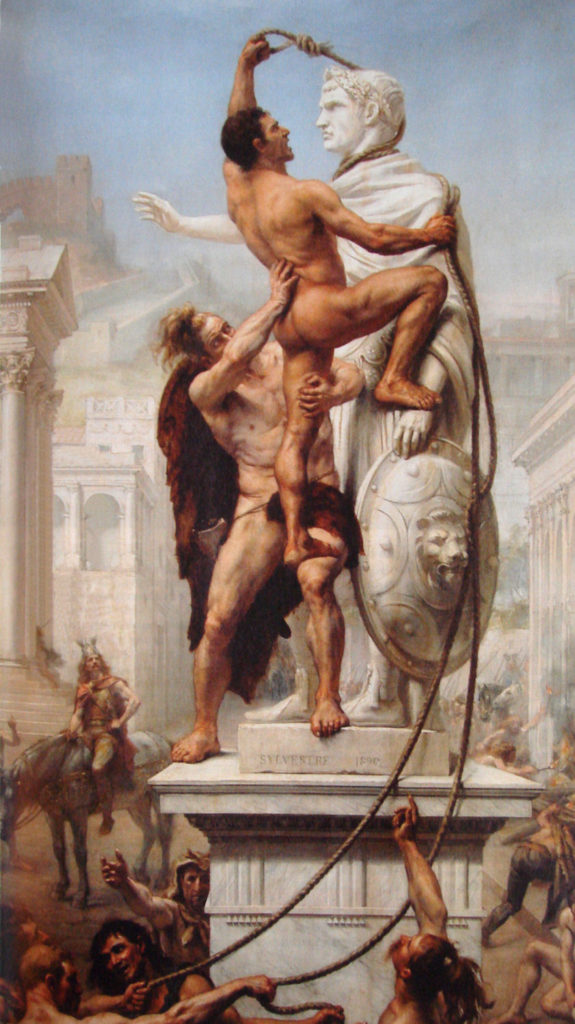

Brennus (born 4th century BC, died after 387 BC) did what it would take barbarian warlords nearly another 800 years to repeat: take Rome. A Roman army met the Gauls eleven miles north of the city in July 387 BC – and was annhilated. The panicked citizens fled, leaving only the Capitoline Hill defended, and the Gauls sacked Rome. Brennus and his men beseiged the Capitoline for seven months: the defenders were only alerted to one night-time assault by the honking of the sacred geese in the temple of Juno. In the end, the Romans bought Brennus off with a thousand pounds of gold but when the Romans weighed out the gold to save their city, they found the wily barbarian had brought fixed weights to the weighing and Brennus threw his own sword onto the scales, famously saying, “Vae victis!” (“Woe to the conquered!”).

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Clovis

The reign of Clovis, the first king of the Franks, marks a decisive shift from barbarian warlords fighting over the last pickings of the Roman Empire to kings ruling new kingdoms. The father of Clovis, Childeric, was a pagan: his tomb contained a gold bull’s head and three hundred garnet-set gold bees. But Clovis, under the influence of his wife, Clotilde, converted to Catholicism, thus setting the religious template for his people. By this time, Clovis had already conquered and assimilated the smaller Frankish kingdoms and, in 486, he defeated the last representative of the waning Imperial power at the Battle of Soissons. Clovis was king but he had no interest in proclaiming himself emperor. Europe, with its patchwork of competing nations, was struggling towards birth.

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Attila the Hun

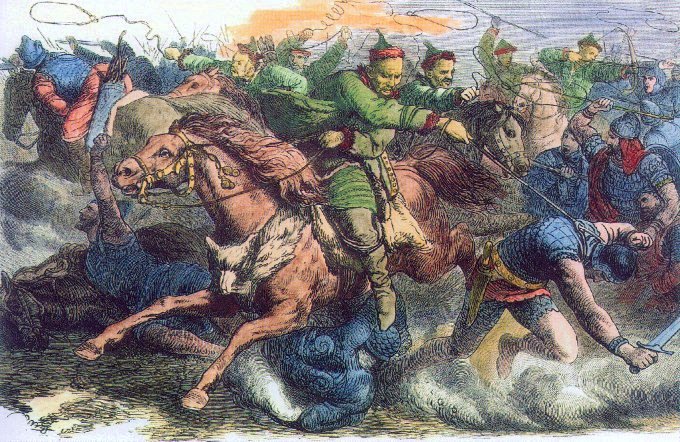

The most famous barbarian of them all never took Rome. First, Attila attacked the Eastern Empire, forcing it to pay annual tribute of 2,100lbs of gold. Having extracted all he could from the Eastern Empire, Attila needed a pretext to attack the Western Empire. In 450, the emperor’s sister provided it. Honoria had had an affair with her estate manager and become pregnant. The manager was executed and Honoria married off to an elderly senator. Determined to escape, Honoria sent a letter and her ring to Attila, asking his aid. Attila demanded half the Western Empire as dowry and invaded. The Roman general, Aetius, met Attila in battle at the Catalaunian Plains and forced him to withdraw. The Hun was beaten. But not defeated. In 452, Attila attacked Italy. An embassy, including Pope Leo I, went to meet him and, somehow, persuaded him to withdraw. In the end it was not battle that defeated Attila but his own body: taking yet another wife, he retired to bed after drinking an inordinate amount, only to be found dead the next morning, next to his hysterical bride.

The Ultimate Accolade for a Writer

This was said to me yesterday.

“I knew I recognised your name. I’ve got your book in my toilet.”

I can now die content!

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Alaric

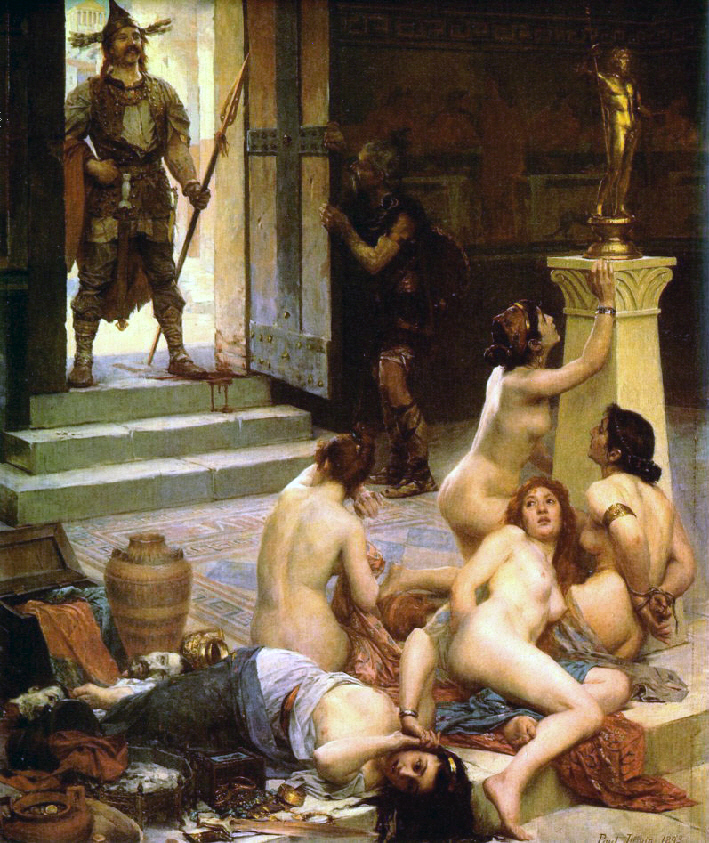

Alaric was the barbarian who finally did what others had tried to do for centuries: sack Rome. When Emperor Honorius, holed up in Ravenna and protected by the surrounding marshes, refused to negotiate, Alaric and his Goths turned on Rome. They’d already beseiged it twice in an effort to get the Romans to pay up. On the night of 23/24 August 410, the Salarian Gate was opened to Alaric. For three days, the Goths plundered the Eternal City, although with more restraint than usual: this was more asset stripping than rape and looting. The city had not been taken by an enemy for nearly 800 years. The myth of Roman invincibility irrevocably broken, Alaric headed south, aiming for Africa, but died of natural causes.

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Arminius

A German raised in Rome, Arminius nevertheless appeared a thorough-going Roman: fluent in Latin, an equestrian, a trusted auxiliary to the legions bent on conquering Germany. So when Arminius told the governor, Publius Quinctilius Varus, of a revolt, Varus had no hesitation in letting Arminius guide three legions into the depths of the forest. But Arminius had tricked him. Unknown to the Romans, Arminius was plotting against them and he had forged alliances among the German tribes. Having lured the legions far into enemy territory, Arminius slipped away. The attack, when it came in the Teutoborg Forest, was devastating. Strung out, the legions were annihilated, three imperial eagles captured, and Varus fell on his sword. The battle was one of the most decisive in history. Therafter, Rome made its frontier at the Rhine. However Arminius himself later fell victim to the jealousy of rival German nobles, who assassinated him in 21AD.

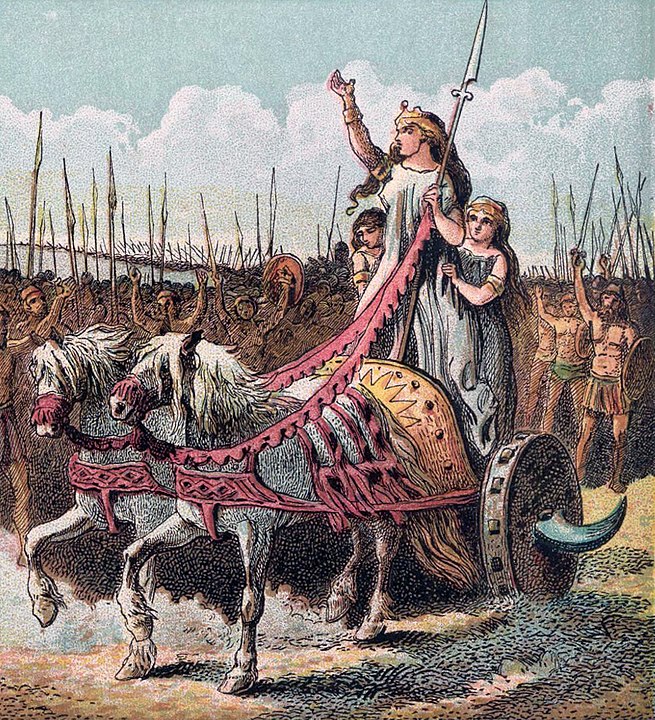

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Boudicca

Boudicca, queen of the Iceni tribe of East Anglia, saw her daughters raped when grasping Roman administrators attempted to steal her inheritance. She was flogged. Mistake. Boudicca led the British tribes in revolt, first attacking Colchester (Camulodunum). The Ninth Legion, hastening to put down the revolt, was destroyed. Gathering men as she went, Boudicca headed to London. When she arrived, she killed anyone who had stayed – 70,000 according to the Roman historian Tacitus – and burned what was left. Archaeologists can still see the red layer of Boudicca’s burning. Seeking battle with the Roman governor, Suetonius Paullinus, the queen of the Iceni marched north. Boudicca’s mistake. 10,000 Romans defeated Boudicca’s army of over 100,000. Boudicca herself either died from poison or illness.

Descartes’ Oven

On the night of 10 November 1619, the 23-year-old René Descartes, a soldier in the army of the Duke of Bavaria despite being a Frenchman, was stationed in Neuborg on the River Danube. It was bitterly cold and Descartes, a slight man sensitive to the cold, sought escape from the wind by sleeping in an oven. Later writers have questioned if he really meant an oven, arguing that he was referring to a room that was heated by an oven. After all, there aren’t that many ovens that a grown man can comfortably fit into. However, what happened next suggests that Descartes might have meant exactly what he said. For in this dark space, cut off from the rest of the world, he had a series of three dreams that proved formative of his future intellectual life. In these dreams, he believed a divine spirit had shown him the secret of analytical geometry – the Cartesian system we use today – as well as revealing that all that is true is joined together. Thus by finding one certain truth, he could go on to reveal all truth. It was not long after these visions that Descartes formulated the basis of his method of philosophy, the certainty that “I am, I exist”. As to the importance of the oven, Descartes, with his knowledge of Plato, would surely have seen its dark embrace as the modern restatement of the Cave from which Plato ascends to true knowledge of the eternal forms.

The Calculus Competition

In science, there’s no glory for second place. So when it came to claiming priority on the discovery of calculus, one of the key tools of modern mathematics, it’s little surprise that a dispute developed between Wilhelm Leibniz and Isaac Newton, both of whom had discovered methods of calculus independently, as to who had been first. But what is surprising is the dirty tricks both men stooped to. By the time the dispute broke into full force, in 1711, Newton was President of the Royal Society, the world’s oldest scientific institution. The Royal Society published an investigation into the question of who had invented calculus that roundly proclaimed Newton its originator and Leibniz a fraud. The impartiality of this report was somewhat compromised when it was revealed that Newton had written the conclusion. As for Leibniz, he was not above altering the dates of his letters and notes to back up his claim. Now it is generally accepted that both men independently invented calculus, although it is Leibniz’s notation that has become the standard way of doing calculus. Looking at the dispute is a reminder that two of the most intelligent men in history may still stoop to lies, evasions and slander to do down an intellectual rival: a playground spat between two superbrains.