In 1487, King John II of Portugal dispatched Bartolomeu Dias to find the sea route round Africa and into the Indian Ocean. But King John didn’t just send ships: he sent spies too. In particular, Pêro da Covilhã, a low-born but multilingual adventurer. Covilhã, with letters of exchange to pay his way, made his way to Alexandria, the entry port to the Islamic world and then, passing himself off as a Muslim merchant, he made his way to Cairo and then on to Aden where he took ship on a dhow across the Indian Ocean, arriving in Calicut, India. Taking notes on the Indian Ocean spice trade, Covilhã then returned to Cairo where he met emissaries sent by John II, giving them his report. Now apparently bit by wonderlust, Covilhã explored Arabia, even entering Mecca and Medina in disguise as a Muslim pilgrim, before venturing across the Red Sea to Mount Sinai. From there, the indefatigable Covilhã headed to Ethiopia, the Christian kingdom in the heart of Africa and the probable source of the legends of Prester John. The ruler, Eskender, received Covilhã well but refused to let him leave. Thirty years later, a Portuguese embassy met their countryman, still living in the court of the kings of Ethiopia.

Blog

Taking Care of Business

Although William had made every effort to convince his magnates, his people and the wider world of Christendom of the justice of his case, yet the duke was old and wise enough to know that war was war, and even a war fought under God’s banner might turn against him. So, as part of his preparations, William nominated his eldest son, Robert Curthose, to succeed him as Duke of Normandy in the event of his death, and saw that Robert also signed William’s gifts to his new abbey. Curthose – a nickname – means short pants and suggests the difficult relationship between William and his elder son. Amid their other preparations, the Norman magnates spent much time setting their affairs in order. Everyone involved knew they were embarking on a do-or-die enterprise, and most of them sought to ensure they had settled outstanding disputes and matters of inheritance before they left.

Getting God On Side

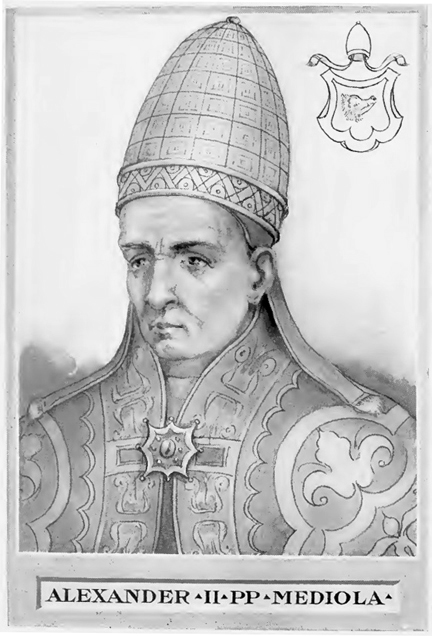

Soon after he heard that Harold had been crowned king, William sent an embassy to Pope Alexander II in Rome, asking papal support for his projected invasion of England. Although the text has not survived, the case William made must have been persuasive: it no doubt rehearsed the familiar points of Edward’s promise of the throne and Harold’s perjury in swearing on holy relics to support William’s claim to the crown, and the pope soon decided in William’s favour. As mark of his support, Pope Alexander sent a banner with William’s returning messengers and instruction that England’s clergy should submit to William as king. For William, this was further proof that God was, indeed, on his side.

Adventures with Words: Felix Unlimited by Andrew Norriss

Felix Unlimited by Andrew Norriss

Quietly, without any fuss, and entirely unnoticed by the literary establishment, Andrew Norriss has become the best writer for children today. Not entirely coincidentally, this also explains in large part why he has become such a great writer. ‘Quietly’ because this is not the sort of writing that draws attention to itself but rather is so skillfully done that the art behind and supporting it disappears entirely. ‘Without any fuss’ because the characters who people Andrew Norriss’s books are exactly the sort of people who do live their lives ‘without any fuss’, not calling attention to themselves but getting on with living in the way that the English were once celebrated for and that still continues, away from the distorting glare of anything to do with the media. Andrew Norriss writes the Drama of the Good, of people who are attempting, each by their own light, to do the best for themselves and their families and friends. It is how most people, away from the corruption of politics or media, generally live and Norriss makes these people the heroes of his stories. The more sceptical reader might ask, where then is the conflict, the tension to provide the petrol for the narrative engine? It is there in life itself, in its pitfalls, straitenings, misadventures and all the limitations and constraints that attend upon being a particular person living in particular circumstances in a particular time and place. To exist at all is to be filtered from limitless possibility and to be inserted into time and place. This is the drama of existence in its purest form, freed from the crabbing effects of the storybook villain with all his fake freedom: it is the story of the conflict with being itself, sometimes in its most recalcitrant forms and sometimes with its most generous face on – and usually in the same Andrew Norriss story!

As for being ‘entirely unnoticed by the literary establishment’, that is a result of the stories having nothing to do with the sort of fashionable tropes and passing political fads that form opinions and tastes among this self-selected and self-satisfied coterie. Most of the literature that supports this establishment is reflective, mirroring back its own attitudes on itself to its own self-aggrandisement – there is nothing better calculated to increase one’s own vanity than to have one’s beliefs fed back in a slightly offset manner. But Andrew Norriss is doing something that Rudyard Kipling did in the 19th century: he is writing about the sorts of people who would normally never feature in proper literature. Kipling wrote of the everyday soldiers of the Empire, he wrote of fishermen on the Grand Banks and engineers on the Indian Railways, of an orphaned Indian boy and a fierce little mongoose, he wrote of men who made things and drove things and did things, very far from the literary salons of the century. Andrew Norriss writes about children who are kind and considerate, and in Felix Unlimited he writes of a boy who wants to run a business. Entrepeneuers, even junior entrepeneurs, are not the sort of people that writers meet very often and even less so do they feature in the academic circles of the literary elite. But when the history of the 21st century comes to be written I strongly suspect that Elon Musk will be written about long after Philip Pullman has been forgotten. Andrew Norriss writes about a boy who likes starting businesses, who keeps trying even when things go wrong, and how they go write. Even the boy’s uncle, a very successful businessman who in any other story would be a conniving capitalist ready to defraud his nephew, in this story proves honourable and helpful. Anyone thinking of starting a business could put aside the start-up manuals, with all their dreadful management speak, and just read this book instead. It’s all there, everything necessary to start and get a business going, within the context of the most delightful story. Felix Unlimited indeed!

1066: The Men Who Would Be King

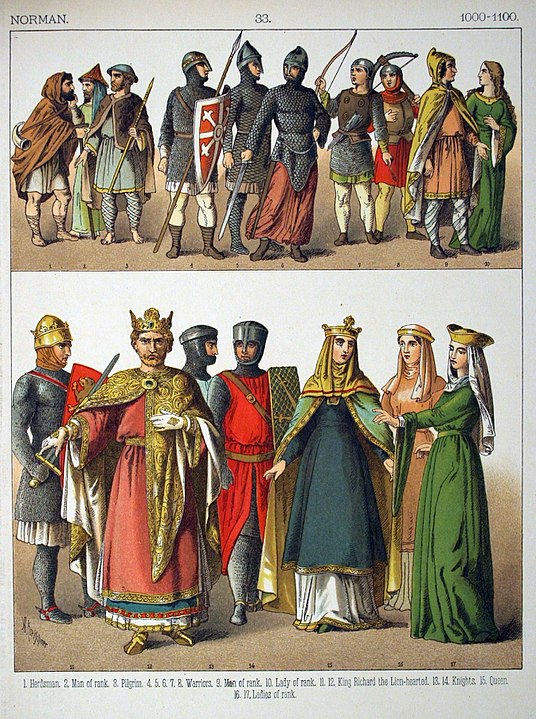

Harold, England’s most powerful man, had made himself king. But as Ealdred, Archbishop of York, placed the crown upon his head, Harold knew he was going to have to fight to keep the throne. There were no fixed rules of succession in 11th-century England. The new king should, ideally, be a blood relative of the dead ruler but might trumped claims of blood. And the only available blood relative to Edward was the young – no more than 13 – Edgar Ætheling, the grandson of Edmund Ironside. ‘Ætheling’ is an Old English title meaning someone who is throneworthy: Edgar was a suitable candidate for the throne.

But the crown did not rest upon blood alone. The reigning king might nominate his successor, and the sources indicate that Edward, on his death bed, did give his blessing to Harold as the man to succeed him. Unfortunately, Edward had also made such a promise to William, Duke of Normandy, and probably to Edgar Ætheling’s father too – and thus to Edgar himself.

Finally, there was the choice of the magnates of England. A king could not rule without their assent and, in choosing the new king, theirs were the most powerful voices. Assembled as they were, there can be no doubt that England’s magnates chose Harold as king; a choice made easier by the fact that Harold had cemented an alliance with the new earls of Northumbria and Mercia, Morcar and Eadwine, by marrying their sister, Ealdgyth.

The cast had assembled. It remained for the fatal drama to be played to its end.

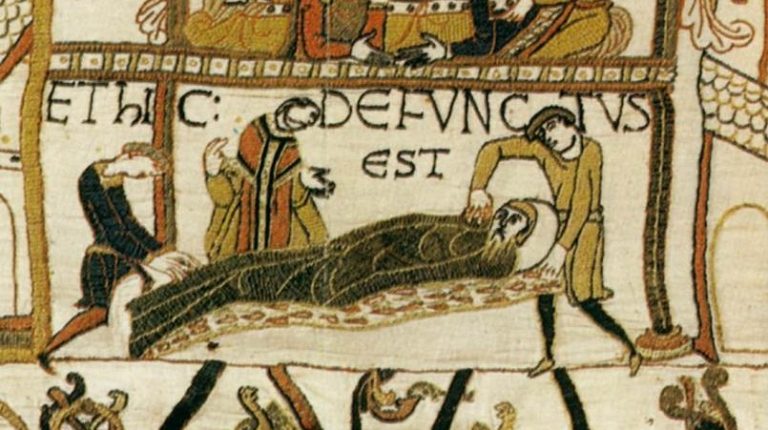

The Death Bed of Edward the Confessor

Did King Edward give the crown to Harold Godwinson, his most powerful earl, as he lay dying on 6 January 1066? The sources disagree, although most do aver that Edward did give rule of the kingdom into Harold’s hands. However, the life of Edward, commissioned by his queen, tells us who was with him on that fateful day: Edith herself, her brother Harold, the archbishop of Canterbury and the steward of the palace. The Bayeux Tapestry reproduces this scene. But what exactly did Edward say? Again, according to the Vita (Life) of Edward, the king commended the queen and the kingdom to Harold’s protection. Not exactly a ringing endorsement of Harold’s kingship – although admittedly the king was dying at the time. But, in England, the king’s wish did not determine his successor; in the end, that was a matter for the magnates of the country. And Harold had spent many years cultivating his contacts with them carefully. So it was no surprise that they chose Harold as king, and saw him crowned the same day as Edward died. The king was dead, long live the king. Or so they hoped.

Adventures with Words: Nameless by Dean Koontz

Nameless, series 1 by Dean Koontz

First, the necessary warning: Nameless is actually a series of six novellas, each readable in an hour or less, with each having its own title. The stories are episodes but disconnected save in having the same protagonist, the Man Without A Name (oops, someone has used that already, let’s call him ‘Nameless’ instead) who sets out in each story to bring truth and an appropriately sticky ending to a killer, swindler, abuser or similarly appalling villain. Nameless is supported by a mysterious organisation that provides him with his assignments and all the necessary information and material, from guns to accommodation, to carry out his assignments, but Nameless himself cannot remember anything about his past beyond the last two years. The series of six novellas carry hints as to his past until in the final one in this first series, Memories of Tomorrow, Nameless learns something of who he is and who he was and why he is doing what he is doing. I won’t give it away but the answer is somewhat more prosaic than the intriguing metaphysical paradox that lay at the heart of Innocent, another Koontz novel that riffed on this same idea.

By my patented Koontzometer – my reading device for locating Dean’s huge ouput on a scale that ranges from the marvellous to the dreadful – I put this Nameless series as a solid to good read: each novella pulls you in and pulls you through to the end and they make excellent bedtime reading: just long enough to keep you up past your normal bedtime but not too long to make you into a shuffling zombie the next day. However, I am not sure that I will bother with Nameless series 2 where top-drawer Koontz would have me reading the next series already. I think, when I next want some quick reads, then that will be the time.

The Scandalous Life and Death of Swein Godwinson, Harold’s elder brother

Swein Godwinson, the eldest son of Earl Godwin and Harold’s elder brother, led a tumultuous life. According to the man himself, he was the son, not of Earl Godwin but of King Cnut. However, his mother denied the claim vehemently. In 1046, Swein abducted Eadgifu, the abbess of Leominster, intending to marry her and claim the Leominster estates. When the king refused to agree to the marriage, Swein released Eadgifu, who returned to Leominster. But her abbey was disbanded, which suggests Eadgifu may not have been an entirely unwilling abductee. Swein fled to Flanders. In 1049, Swein returned, hoping to reclaim his territories, which had been split between Harold and a cousin, Beorn. Beorn eventually agreed to help Swein, but Swein ended up abducting Beorn too. The end for his cousin was worse than for the abbess: Swein murdered him. As a result, Swein was outlawed again. However, Earl Godwin engineered his forgiveness, but when the Godwins were exiled in 1051, Swein left the rest of the family to make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem and atone for his sins – these being so heinous that he went barefoot. But Swein, purged of his sin, died on the way back before he could sin again.

Five Things About: Harold Godwinson

Harold’s mistress, Edith Swanneck, may have been Eadgifu the Fair, one of the largest landholders in England before 1066.

The estates of the Godwinsons produced an income of £8500 a year in the 1050s; the king’s estates gave him £6000 per year.

Harold’s mother, Gytha, was Danish, the daughter of one of Cnut’s nobles. When Swein, her eldest son, claimed that Cnut was really his father, Gytha assembled the noblewomen of Wessex to swear her faithfulness to Earl Godwin.

Harold’s sister, Edith, the wife of King Edward, commissioned a biography of the king after his death which served to commemorate him and exonerate her from blame for the disaster that befell her family in 1066.

Wulfnoth, the hostage Godwinson, remained William’s prisoner until William freed him in a general amnesty on his deathbed, only for William’s heir, William Rufus, to promptly imprison him again. Wulfnoth died in 1094. By then he had been a prisoner for 43 years.

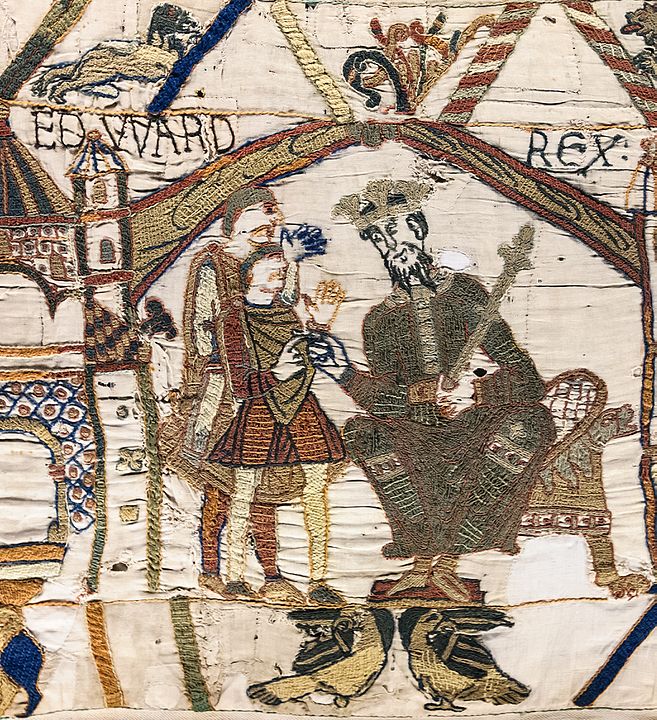

When William Met Edward

William knew Edward, future king of England, from his boyhood. For when William was born, Edward was a young prince living in exile with his mother’s relatives in Normandy. William was in his early teens when Edward returned to England, the unexpected king. But Edward retained close links with the court where he had grown up and after the expulsion of the Godwine family in 1051, Edward sent across the Channel for William to come visit. According to one of the versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, William did just that, visiting Edward in October or November of 1051. The Duke came as the king’s vassal, but the king had a great gift to impart to his new vassal: the promise of the throne. With Edward rid of the Godwines, he felt himself able to promise the throne to whomever he wished, and William was the son of the people who had sheltered and helped him through his long exile. So William returned to Normandy convinced that, if Edward remained childless, then the throne of England would come to him. But did Edward have the authority to promise the crown to William? There were no hard and fast rules of succession; the king’s wish was important but it was not paramount, for the succession depended also on the assent of England’s magnates, and they were certainly not keen on a Norman king, and even less so once the Godwines returned to power in 1052.