What is Western esotericism? You may well ask, and the author, a distinguished Dutch academic, spends the first chapter trying to answer the question and worries away at it in asides throughout the book. Perhaps the best way of describing it, now, is marginal knowledge: the bits that don’t fit neatly under the tags of arts or science. But perhaps a better way of expressing it, which Hanegraaff does not say in his book, is that esoteric knowledge bears the same relationship to human understanding that professional sportsmen do in comparison to amateurs. Let me explain. Back in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, when the Western esoteric tradition was taking form as an agglomeration of knowledge drawn from sources as diverse as Platonism, Hermes Trismegistus, Christian mysticism, Kabbalah, Pythagoreanism and early natural philosophy, there was a legitimate question as to the nature of knowledge, namely, could everyone understand it? Once some piece of knowledge was uncovered, did it then become open to all, like opening Tutahkhamun’s tomb. Or was the knowledge accessible only to those who had trod the path to its attainment? To make this clearer, I can play cricket. I know how to play a cover drive, a backward defensive, and so on. But no matter how much I practise, I will never make a professional cricketer, let alone ascend to the ranks of an all-time great such as David Gower (I can still remember the first time I saw the teenage Gower bat in a Sunday League match on Sunday on BBC2 when, in the golden light of a September evening, he seemed a curly haired god bestriding the world of mortals, sending the ball where he willed with the merest flick of his wrists: that is the mark of true greatness in any field, be it sporting or artistic). In some fields, mastery is beyond all but a small elite of people. The question in the early modern period was whether knowledge was like that. The answer we went for, the answer of the modified form of natural philosophy that became modern science, was no. It might take an Einstein to discover relativity but having made his way up the mountain of knowledge he can bring its fruits down to the rest of us. However, western esotericism holds that there are some forms of knowledge that can only be gained by those who climb the mountain: they cannot be shared, only seen. Another analogy would be my knowledge of the colour red. The only way I can truly share this with you, if you have never seen red, is to give you a tomato and say, “Look, this is red.”

That is western esotericism. Hanegraaff is one of a number of scholars now working in this previously little studied field and he is a fervent advocate of studying it in a historical manner, tracing influences, lineages, and developments in its history. What he is adamant scholars should not do is engage in any evaluation of the truth of what the esotericists claim. This, Hanegraaff claims, goes outside the purview of scholarship in this field. However, by deliberately laying aside questions of truth, when Western Esotericism is fundamentally a search for truth, is like trying to study music without listening to any music. Yes, you might learn something about music, from its development to biographies of its practioners to some simple musical theory perhaps, but you will miss the heart, the key, the life; you will miss the music itself. Hanegraaff’s approach misses the music.

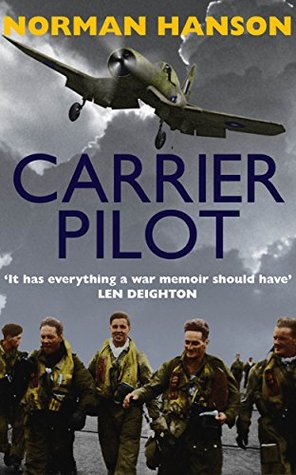

So, overall, the book provides a good overview of Western esotericism, clarifies some of the people and schools involved in its various traditions, while remaining little more than an exercise in classification. On a completely separate note, the book has one of the ugliest covers I have ever seen, and one that has really no connection to the subject. The paper the front cover is made from also feels peculiarly unpleasant to the touch. Overall, an interesting but limited approach to the subject.