The History of Mont Saint-Michel part 3: A Miracle in Stone

Faced with a lax community of monks, Richard the Fearless (933-996) brought in those great renewers of monastic life: the Benedictines. Richard gave the epicurean monks of the mount an ultimatum: accept a properly rigorous monastic life as a Benedictine or leave. All but one left. This year, 966, marks the start of the Benedictine foundation that would work miracles in rock.

As the power of the Dukes of Normandy grew, so did their reliance on the protection of their great patron, St Michael. In 1020, Richard the Good (ruled 996-1027), son of Richard the Fearless, commissioned Abbot Hildebert to build a new abbey church upon the mount.

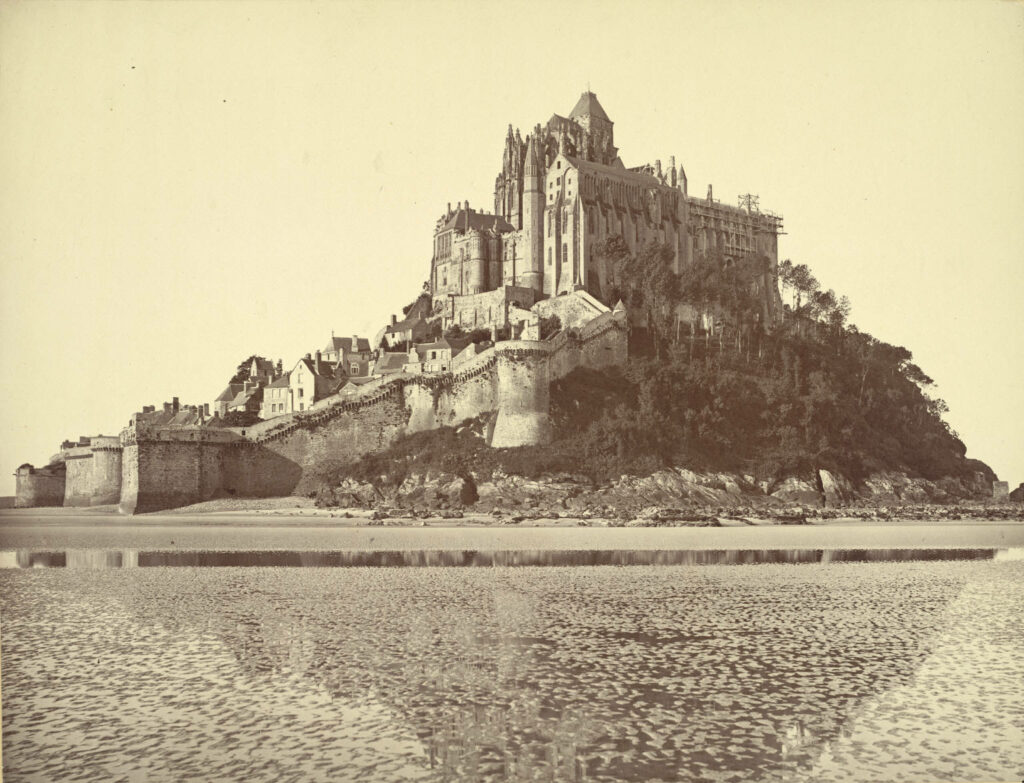

Romanesque architecture was in its infancy, but in their ambition to glorify the archangel, Richard and Hildebert asked extraordinary things of their new church. The rock of St Michel was shaped like a sugar loaf, rising 78.6 metres (258 feet) above the mean sea level. The obvious architectural choice would have been to cut the top off the mountain to create a solid and level foundation for the new church. But that would have been to step down from heaven. Instead, Abbot Hildebert took the apex of the rock for the the ground level of his new church, and built out in all directions to provide the foundations.

The apex of the rock is the centre of the church, the crossing point where nave and transept meet and join. On this rock, Hildebert built his church, the central tower rising directly from the apex of the mount, supported by the four piers that still hold the tower up, thrusting the statue of St Michael (a 19th-century addition) into the sky. Abbot Hildebert and his successors built out westward about two hundred feet from the cross of the church.

A great medieval church never being properly finished, they were still building 150 years later, when Abbot Robert de Torigny rebuilt the west front of the church with two towers. That was two towers too many. One fell in 1300. Slowly, slowly the west front gave way, so that in 1776 the whole façade and three spans of the nave had to pulled down. Today, four of the seven original seven spans of the nave survive.

Looking up at the abbey church today, standing serenely above the world, it seems untroubled and stable. This appearance masks the reality of its history. For the abbots built out as enthusiastically eastwards as they did westwards, with the same result. On the east, Abbot Hildebert’s foundations stood until 1421, when they gave way while the mount was beseiged during the Hundred Years’ War. It was rebuilt and completed in 1520 in a last flowering of Gothic architecture. Stand in the western door and you can see the original and terminal styles of medieval architecture, the Romanesque and the Gothic, together, the sober spans of the Romanesque nave framing the flamboyance of the Gothic choir.

0 Comments