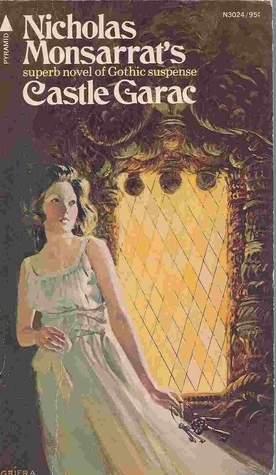

I found this slim novel in a second-hand bookshop (it’s long out of print) and picked it up because I have read Monsarrat’s superb novel of naval warfare during World War II, The Cruel Sea, and was curious to see what the rest of his work was like.

Well, it’s not nearly as good as The Cruel Sea – but then few books are. It’s interesting how some authors have one great book within them, but no more than that. In Monsarrat’s case, it was because in The Cruel Sea he took his wartime experiences and distilled them with his writing craft, making of them a book that endures. But absent such source material, in a book like Castle Garac, and we are left with authorical craft and pure storytelling, but storytelling of its time. It’s interesting how much the simple craft of telling a story is affected by its time and culture, from the rhythm and pace of the prose, through the choice of words, to the subject matter. As such, popular fiction from long ago (this was first published in 1955) is a rather good way of appreciating cultural changes, for good and ill. Far too many people simply go through books like this and pick out things that offend their modern sensibilities without thinking how the sensibilities of the past would be offended in turn.

The story itself is not whodunnit but rather a what-are-they-planning: mysterious rich couple enlist penniless writer for a scheme that’s clearly crooked but the payoff is in learning just how it is crooked. It’s a swift and easy read. If you should see the book, lying neglected in a second-hand book shop, pick it up and read it. You will make an old book very happy.