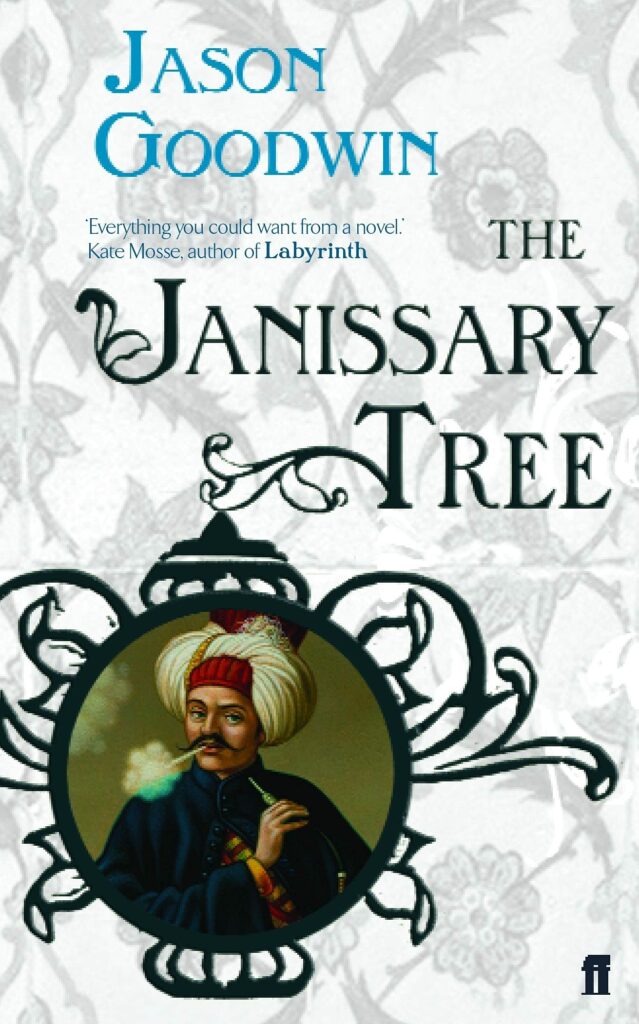

This is a very fine addition to the canon of historical detective stories set in exotic locations – but, if you’re like me, you will have finished reading The Janissary Tree with one question uppermost in your mind: surely eunuchs can’t have sex?

Yes, the novel gives a wonderful sense of the declining years of the Ottoman Empire, when a gentle cloud of futility descended over the great city that was once Constantinople and the pashas settled into civilised and genteel inaction. Its hero and his friends and rivals are finely drawn, vivid creations, providing further insights into this strange world.

But could a eunuch really have sex? Because that’s exactly what Yashim the Eunuch, the detective hero of the story, does, and with a particularly beautiful Russian noblewoman at that. Which, so far as I had thought (although admittedly I hadn’t thought much on it), rather ruined the point of creating a eunuch in the first place. Surely, I thought, the point of castrating men was to ensure that they could not interfere with the women of the Sultan’s harem, or any other women for that matter. But here was Yashim doing exactly what I had always supposed was impossible for a eunuch to do.

So, having finished the book, I looked further into the matter (well, did some Google searches, to be honest) and the answer appears to be: maybe. Could be possible, or then again it might be impossible. Pretty well par for the course for internet research. So, dear reader, I leave the question in your hands: do you think it is possible for a eunuch to have sexual intercourse? (Although I do encourage you to read this excellent detective story as a means towards starting your research.)