A Venetian himself, Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697-1768), or Canaletto as he is better known, made his name by painting views of his city that were marketed to British gentry making the Grand Tour. When war stopped visitors coming to Italy from England, Canaletto moved to England, painting views of the Thames among other places. But nothing matches the light-drenched canvases of his views of Venice.

History

How St Mark Came to Venice

In 828, two Venetian merchants, Buono of Malamocco and Rustico of Torcello, were in Alexandria doing business. Alexandria had been conquered by Muslim armies and in 828 it was under the control of the Abbasids. Speaking to the priests of the church of St Mark in Alexandria, Buono and Rustico learned that the priests feared for the safety of the relics of the saint that they kept in the church, and indeed their own safety under the Abbasids. Hearing this, the Venetians offered the priests safe passage back to Venice – at the price of bringing the body of St Mark too. The priests agreed and, taking the body from its sarcophagus and replacing it with a less eminent corpse, they put the saint’s remains in a chest, carefully covering the body with a layer of salt pork and cabbage, before loading the chest onto the Venetian ship. Before setting sail, Muslim customs officials came on board to inspect the cargo but, seeing the pork, they recoiled in horror without digging any deeper. Safely out to sea, the saint’s body was taken from the chest and placed in honour on deck, surrounded by thuribles and candles. And so St Mark came to Venice, where he swiftly supplanted the city’s previous patron, St Theodore, in the affection and devotion of Venetians. Mark had arrived by sea and it was to the sea that Venice looked for its fortune; it was a fortuitous, or providential, arrival.

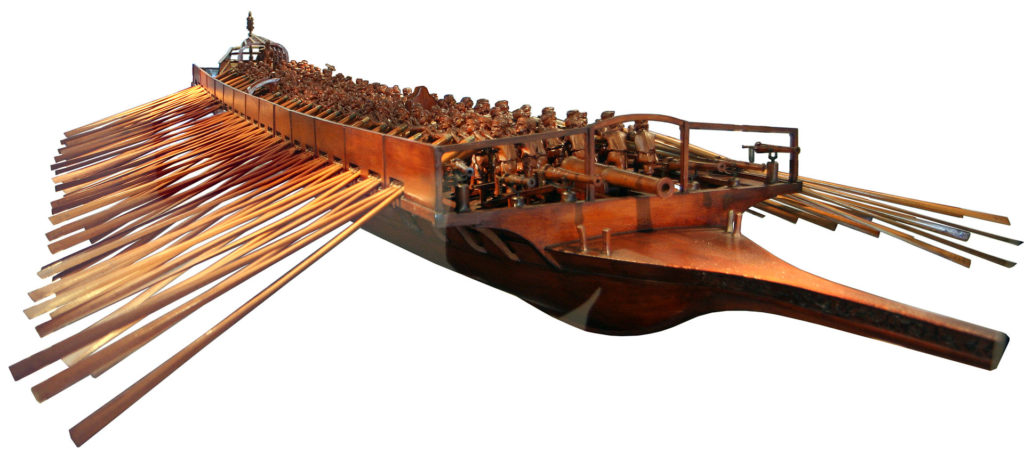

The Venetian War Galley

For the four centuries of Venetian mastery of the Mediterranean, the war galley was the instrument of Venetian power. Shallow drafted, manoeuvrable, and fast, the war galley allowed the Venetians to dominate the sea ways of the eastern Mediterranean. To produce the necessary ships, the Republic created the Arsenal, the largest industrial site in Europe before the Industrial Revolution. Surrounded by walls, the Arsenal could mass produce up to a hundred ships at a time in a way that was unique for the age, with the ships being floated to the different craftsmen in a manner that predated Henry Ford’s production line by centuries. Uniquely among the Mediterranean sea-going powers, Venetian galleys were usually crewed by free men rather than slaves. This meant their ships were not liable to sudden mutinies during battle and that the rowers could take part in boardings of enemy vessels. Venetian galleys also had lateen (triangular) sails, which allowed them to tack into the wind, providing greater manouevrability than square sails. But only the ship’s officers had any protection from the elements, with a tent being erected at the stern. The rowers had little or no shelter, from rain or sun.

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Theodoric the Great

Theodoric (454 – 30 August 526), known as the Great, led his people, the Ostro (‘eastern’) Goths into Italy in 489, defeating Odoacer, the first barbarian king in battle and beseiging him for three years in Ravenna. When Theodoric could not take the city, he negotiated a shared rule and entered the city. All seemed cordial at first but then, ten days later, Theodoric personally murdered Odoacer and his men killed all Odoacer’s family. So one Barbarian Hall of Famer met his suitably barbaric end at the sword of another. Nevertheless, after this bloody beginning, Theodoric strove to maintain peace for the rest of his rule, trying to persuade his people to treat their Roman subjects well. His remarkable mausoleum still stands in Ravenna.

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Odoacer

Odoacer (c.433 – 15 March 493) deposed the last emperor of the western Roman Empire and became the first barbarian king of Italy. Like many barbarian warriors, Odoacer had found employment with the remnants of the Roman army under the command of Orestes, the ‘master of soldiers’. But when Orestes appointed his son, Romulus Augustulus, emperor and refused reward for his men, Odoacer killed Orestes and deposed Romulus. But so powerless had the emperor become that Odoacer let Romulus live, giving him a pension and a long retirement with his relatives. The Roman Empire in the West was finished: the barbarians had won.

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Vercingetorix

Julius Caesar had all but completed the conquest of Gaul when Vercingetorix, leader of the Averni, led an uprising in 52 BC. He defeated Caesar at the Battle of Gergovia but was later forced to retreat to his stronghold at Alesia. When attempts to lift the siege failed, Vercingetorix surrendered to Caesar, so that he could save as many of his own men as possible. Julius, with his eye on publicity, kept Vercingetorix captive for five years so that he could appear in Caesar’s triumph in Rome. Having served to bolster Caesar’s fame, Vercingetorix was strangled a few days later.

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Brennus

Brennus (born 4th century BC, died after 387 BC) did what it would take barbarian warlords nearly another 800 years to repeat: take Rome. A Roman army met the Gauls eleven miles north of the city in July 387 BC – and was annhilated. The panicked citizens fled, leaving only the Capitoline Hill defended, and the Gauls sacked Rome. Brennus and his men beseiged the Capitoline for seven months: the defenders were only alerted to one night-time assault by the honking of the sacred geese in the temple of Juno. In the end, the Romans bought Brennus off with a thousand pounds of gold but when the Romans weighed out the gold to save their city, they found the wily barbarian had brought fixed weights to the weighing and Brennus threw his own sword onto the scales, famously saying, “Vae victis!” (“Woe to the conquered!”).

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Clovis

The reign of Clovis, the first king of the Franks, marks a decisive shift from barbarian warlords fighting over the last pickings of the Roman Empire to kings ruling new kingdoms. The father of Clovis, Childeric, was a pagan: his tomb contained a gold bull’s head and three hundred garnet-set gold bees. But Clovis, under the influence of his wife, Clotilde, converted to Catholicism, thus setting the religious template for his people. By this time, Clovis had already conquered and assimilated the smaller Frankish kingdoms and, in 486, he defeated the last representative of the waning Imperial power at the Battle of Soissons. Clovis was king but he had no interest in proclaiming himself emperor. Europe, with its patchwork of competing nations, was struggling towards birth.

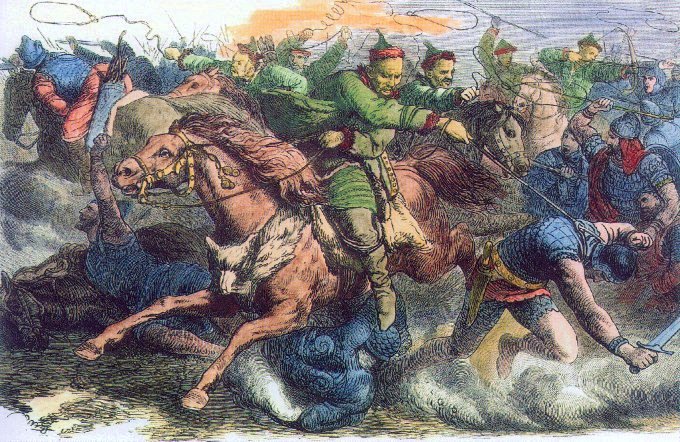

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Attila the Hun

The most famous barbarian of them all never took Rome. First, Attila attacked the Eastern Empire, forcing it to pay annual tribute of 2,100lbs of gold. Having extracted all he could from the Eastern Empire, Attila needed a pretext to attack the Western Empire. In 450, the emperor’s sister provided it. Honoria had had an affair with her estate manager and become pregnant. The manager was executed and Honoria married off to an elderly senator. Determined to escape, Honoria sent a letter and her ring to Attila, asking his aid. Attila demanded half the Western Empire as dowry and invaded. The Roman general, Aetius, met Attila in battle at the Catalaunian Plains and forced him to withdraw. The Hun was beaten. But not defeated. In 452, Attila attacked Italy. An embassy, including Pope Leo I, went to meet him and, somehow, persuaded him to withdraw. In the end it was not battle that defeated Attila but his own body: taking yet another wife, he retired to bed after drinking an inordinate amount, only to be found dead the next morning, next to his hysterical bride.

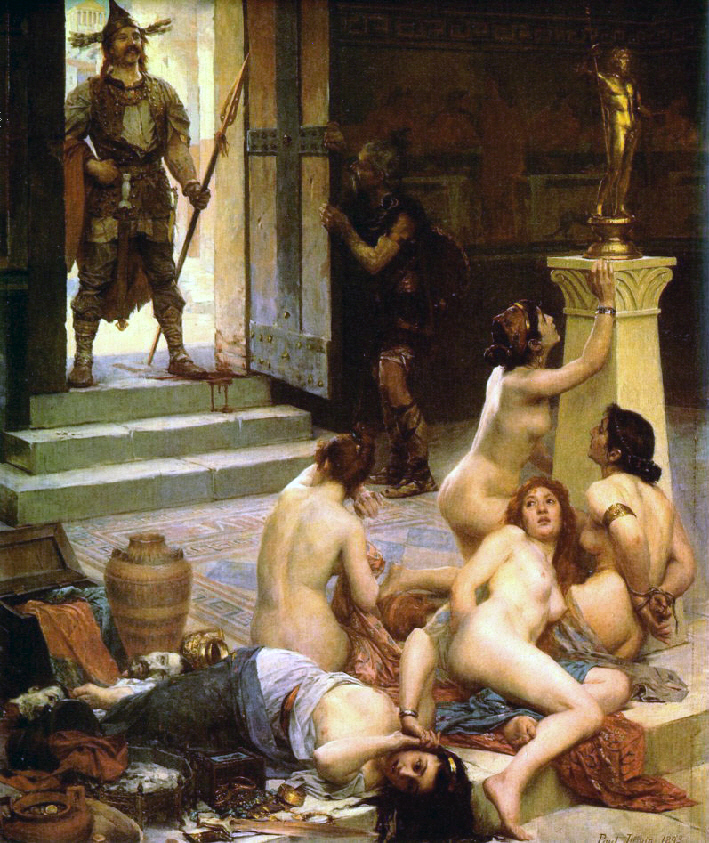

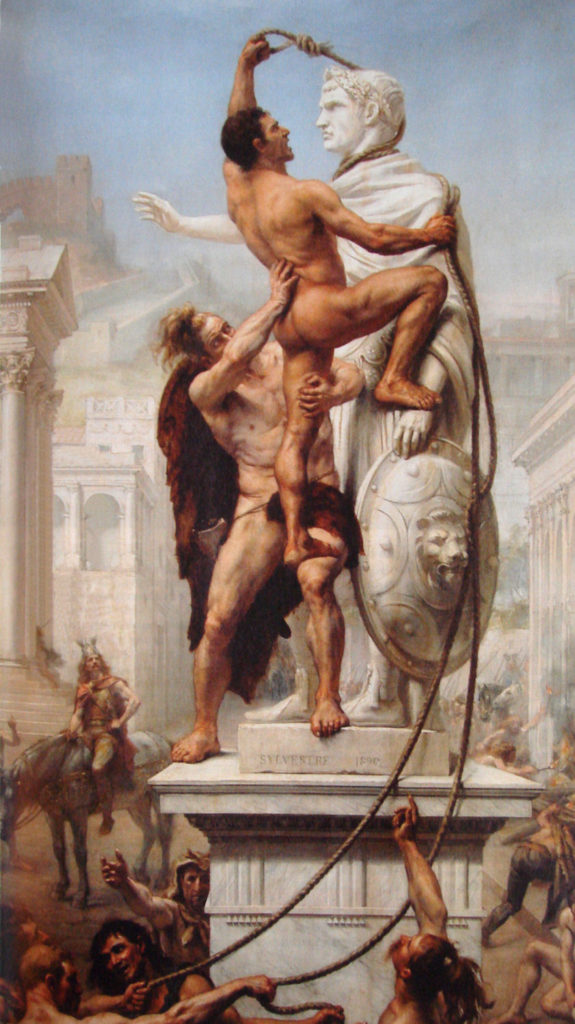

Barbarian Hall of Fame: Alaric

Alaric was the barbarian who finally did what others had tried to do for centuries: sack Rome. When Emperor Honorius, holed up in Ravenna and protected by the surrounding marshes, refused to negotiate, Alaric and his Goths turned on Rome. They’d already beseiged it twice in an effort to get the Romans to pay up. On the night of 23/24 August 410, the Salarian Gate was opened to Alaric. For three days, the Goths plundered the Eternal City, although with more restraint than usual: this was more asset stripping than rape and looting. The city had not been taken by an enemy for nearly 800 years. The myth of Roman invincibility irrevocably broken, Alaric headed south, aiming for Africa, but died of natural causes.