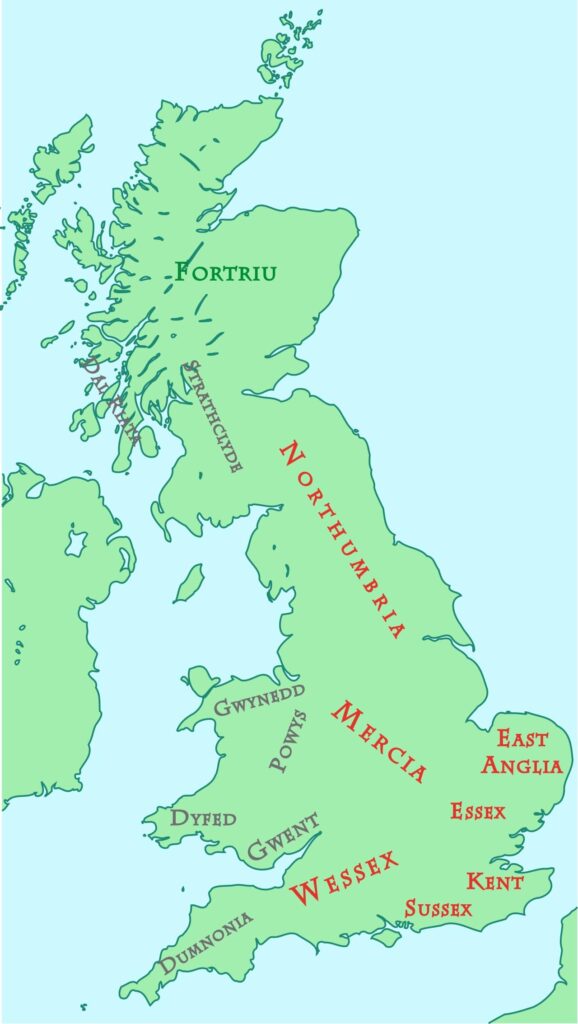

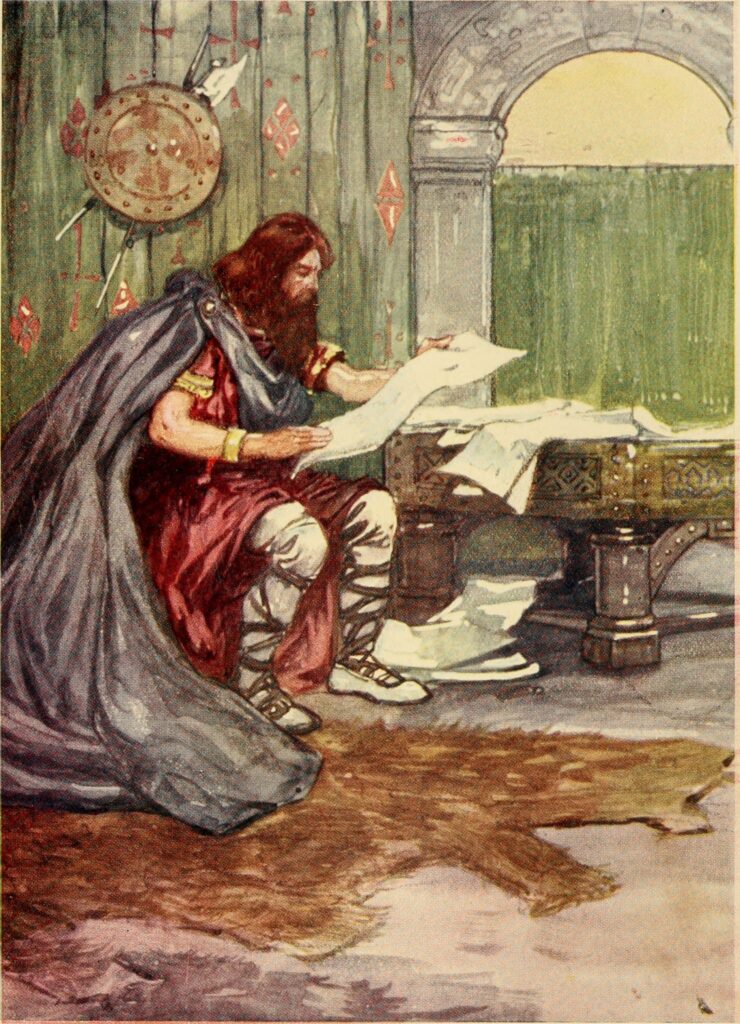

Alfred’s reform of his army was only half the solution to the problem of enabling Wessex to withstand future Viking attacks. Even with a mounted army, the Viking mastery of amphibious operations meant they could still achieve first strike along the long coastline of Wessex, or along its navigable rivers. To protect against the sudden threat of the dragonships appearing on the horizon, Alfred had to improve the defences of his kingdom, and make them accessible to his people. To that end, he set about the most sustained programme of building since the Romans conquered Britain seven centuries earlier.

Alfred built fortresses, burhs (from which comes ‘borough’), right across his kingdom, each of them carefully placed in a strategic location. These were not simply defences, but rather fortified towns, able to function economically and independently, yet able to combine with each other to form a defensive screen across Wessex. The thirty burhs were placed so that no one and no where in Wessex was more than twenty miles – or a day’s march – away from a refuge.

The burhs defended harbours, rivers, Roman roads and the old trackways of Britain. Where Roman or Iron Age forts already existed, Alfred was perfectly happy to reuse and renovate what was on the ground. But where there was nothing he built from scratch. Although we don’t know for certain, it seems likely that Alfred made use of his new standing army in the construction of the burhs. As any commander knows, keeping bored men occupied and out of mischief is difficult. Digging ditches and raising palisades ensured that the army had work to do when it wasn’t fighting. Most of the new burhs were built near Alfred’s existing royal residences. These were already strongholds, but with essentially a fortified town near a royal estate, each helped to defend and support the other.

A burh was not just a fortress but a planned town. The people living in the town provided much of the manpower to defend the burh, and ensured that it would be defended and guarded. In some cases, such as at Winchester, Alfred was simply expanding what was already there but in others he created a town on a green-field site. For the burh to remain effective as a defensive bastion, it had to be a viable economic unit, and land was allocated to each for its supply and provision.

But the building of protected settlements with concentrations of population had the result of kickstarting towns, and their attendant trade and wealth creation, into existence. Although there’s very little left of Alfred’s original burhs, the street plan of somewhere like Wallingford, with its regular grid, probably dates from its foundation. If so, it shows just how ambitious Alfred’s building programme was, for Wallingford covered one hundred acres (forty hectares): the king had created, from scratch, the second biggest town in his kingdom.

In order to support each burh, Alfred created a system of administration that ensured sufficient land and resources were allocated to each burh for its maintenance and its defence. Now Wessex was ready. Let the Vikings come, if they dared.