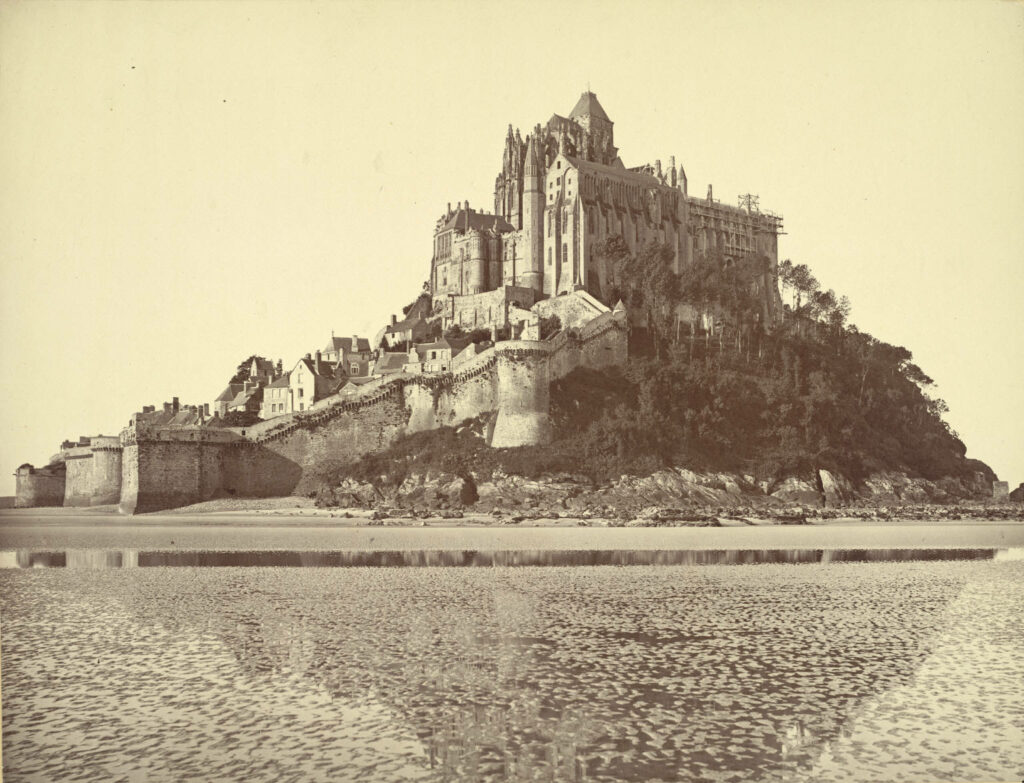

The Mount, set in a tidal bay, did not need defences until the outbreak of the Hundred Years’ War. During the course of the war, battlements were built around the island, and the abbey itself was fortified.

By 1520, the last great addition to the abbey church, the late-Gothic choir, had been completed. It was just in time. In 1523, King Francis I granted the abbacy in commendam to the nobleman (and later cardinal) Jean le Veneur. This was basically a grant for an absentee abbot to milk the abbey of its income. Le Veneur, and the succeeding abbots in commendam, did so, to such an extent that there were barely any monks left at the outbreak of the French Revolution. The rabidly anti-clerical Revolutionary government closed the monastery and turned it into a prison, mainly for priests and religious. They also renamed it Mont Libre, apparently without any intended irony. To haul provisions to the top of the mount, the prisoners had to tread a huge wheel that pulled a cart up a steep incline: wheel, chain and incline (called ‘poulain’ in French) are all still visible.

The Mount remained a prison until 1863, when a campaign by French men of letters, including Victor Hugo, led to it being declared a historic monument. Some urgent repairs were needed to stabilise and restore the building after the modifications made to hold prisoners. As part of the restoration, the spire atop the central tower was added, with the statue of St Michael crowning it.

In 1966, after a gap of over 150 years, monks returned to the abbey. Appropriately, they were Benedictines, and once again the great work of monks, the daily office of prayer and chant, was heard flowing through the choir. In 2001, the Jerusalem Community, a joint institute of monks and nuns, took over at the abbey. They chant lauds and vespers in the morning and evening, with a midday mass; for those wanting to engage more deeply in the spiritual heritage of Mont St-Michel, the Community have a retreat house on the Mount. These are the best times to visit the abbey: as the chant silences the tourist chatter and the sound, more profound than silence, reaches to heaven.

Michael, looking down from his high vantage point, must be pleased.