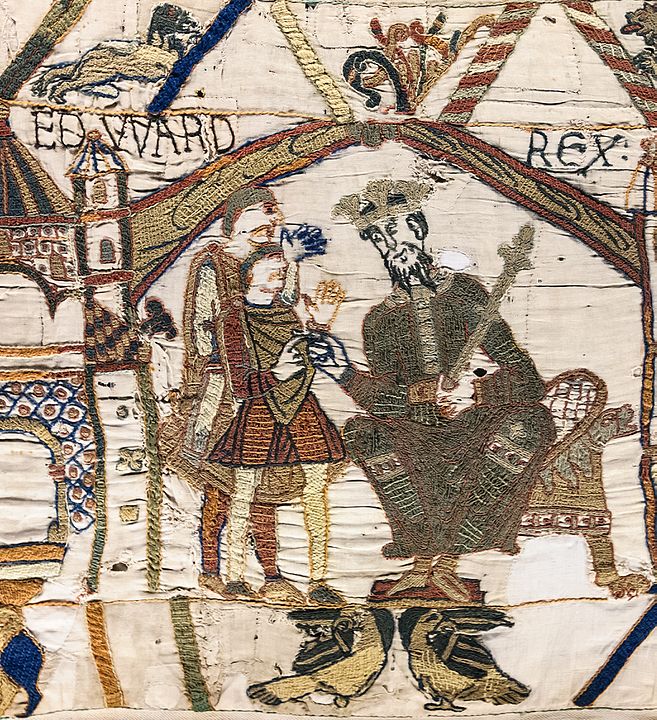

No king in England’s history has been more unjustly forgotten than Æthelstan. This forgetting is all the more poignant in that Æthelstan can reasonably claim to be the first king of England. Not many other nations would flush their founder down the memory hole: Washington adorns dollar bills, every Roman could tell you the story of Romulus and Remus, and Napoleon, the founder of modern France, has had more books written about him than any other human being in history apart from Jesus Christ. But on Æthelstan, almost nothing.

Hopefully, Tom Holland’s marvellous little biography will go some way towards rescuing Æthelstan from his obscurity. With all the excitement that the story deserves, Holland whisks the reader back to 10th century Britain, when the Northmen did not merely launch picturesque, TV mini-series worthy raids, but embarked on expeditions of conquest; this was a country that had suffered two generations of depredations, when anyone living near sea or navigable river went to sleep with the fear that they might wake to find their homes being ransacked and fired, and their children being carried off into slavery. For amid the revision of Vikings as romantic heroes, little attention has been paid to the fact that their most valuable booty was human: men, women and children hauled off to be sold in the slave markets at Dublin, the Viking town that stood at the nexus of the slave routes that delivered captured people to miserable new lives from which they would never return.

Æthelstan, following in the footsteps of his grandfather, Alfred, and his father, Edward the Elder, was a man committed to defending and instilling civilisation in the face of the barbarians. For, make no mistake, for all their accomplishments as explorers and traders, the Vikings were barbarians. Three generations of the most remarkable family in English royal history had made it their lives’ work to first defend and then to reconquer England, and Æthelstan stood at the summit and consummation of this extraordinary familial endeavour. Then, when all seemed accomplished, all was thrown into doubt when the kings of the Vikings, of the Scots and of Strathclyde united against him. The ensuing battle, Brunanburgh, was ‘the battle’ for a hundred years, the battle that ensured that England would be England, and not dismembered. Read Holland’s book and marvel at the scale of Æthelstan’s accomplishments and how much we have to be grateful to him for.