Matthew Arnold’s poem, Dover Beach, laments the long withdrawing roar of the Sea of Faith, the tide of belief slowly receding.

But the thing with tides is, they go out and then they come back in. And, less obviously, tides go in and out at different times in different places. In Britain, religious belief has been in decline for the last half century or so. The same is true of much of Europe. But elsewhere, notably in Africa and China, the opposite is the case.

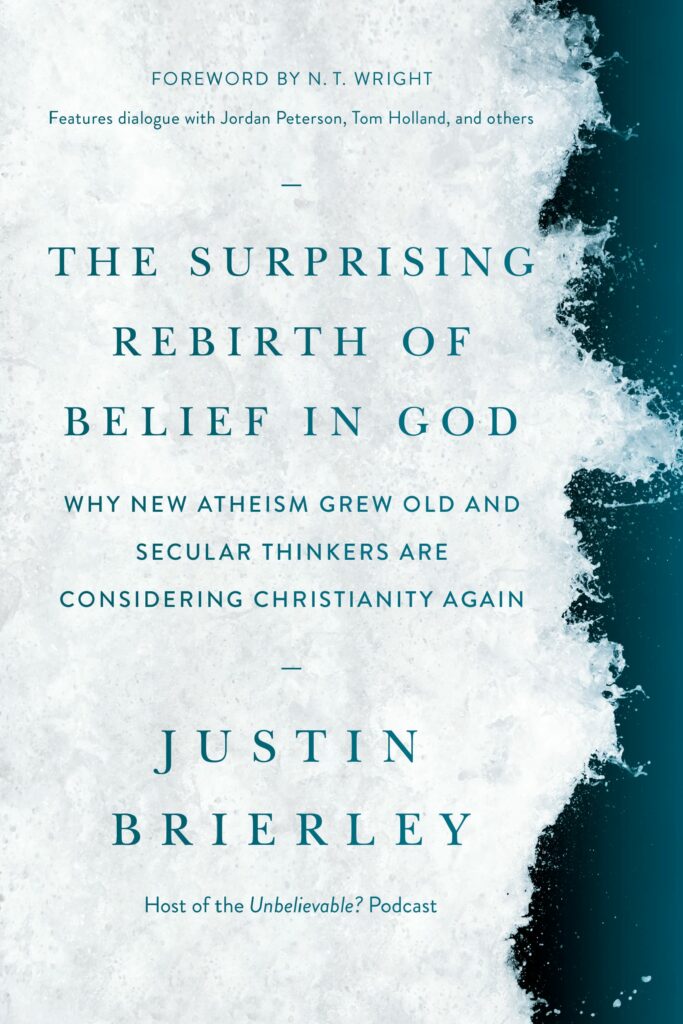

Justin Brierley has been hosting a podcast where he brings together notable atheist and religious thinkers and has them talk, in a civil and constructive manner. And over the decade or so he has been doing this, he has seen, as have I, a distinct change. The millennarian stridency of the New Atheists has lessened to an appreciation of the human value of shared religious belief: no less an atheist than Richard Dawkins now accepts the cultural value of Christianity to the England that he loves.

Other thinkers, such as the historian Tom Holland, have highlighted how the entire foundations of even the most secular Western thought are built upon Christian foundations. The concern for the victim that underlies much modern thought comes entirely from the Christian view of the sacrificial value of the pure victim that is Christ himself.

Apart from Tom Holland, other intellectuals are coming round to the idea of the value of Christianity, such as Niall Ferguson. Outside intellectual circles, it’s interesting to note the increasing number of Premier League footballers who put faith at the centre of their life, privately and publicly, such as Bukayo Saka, as well as celebrity conversions such as Russell Brand.

All these suggest that we may have reached the turning of the tide. Combine this with the fact that atheist and agnostic couples have significantly fewer children than religious couples, and it suggests that the 21st century will see not the death of religion but its rebirth – even in the supposedly secular West.