The katana, a single-edged, curved blade, was the legendary sword of the samurai of Japan. Extraordinary legends have been attached to these blades, from the blood thirst of the Muramasa swords to the holy sword of Masamune, which would only harm that which was evil.

As the pattern-welded blade was rising to prominence and then being replaced by mass produced, inferior blades in Europe, a similar technology was rising in Japan. The technology was startlingly similar, yet very different. The tatara, a form of industrial smelting, was used to extract tamahagane steel and iron from the iron sands that are the main ore source in Japan.

Tamahagane is high quality steel, but the carbon content is variable. The bladesmith separated the steel into highest and lower carbon. The low carbon steel (shingane) was forged into a core and the higher carbon steel was forged into layers which were then sandwiched together around this forged core into a blade shape. The outer blade could be folded many times to form a laminated sword in which the impurities were spread evenly throughout the blade, much like in pattern-welded swords.

Between each forging the blade was coated in clay mixed with ash. This helped to draw out impurities from the steel as it was heated and burned off in the intense heat of the forge.

The skill in forging a katana lay in making certain that the soft core and laminated outer skin were correctly aligned and positioned in the finished blade. Like a pattern-welded blade this skill took a life time to master.

The katana was not heat treated in the same way as a European sword. The softness of the back of the blade was maintained by coating it in a thick layer of clay. The clay was thinned towards the blade edge. This kept the high heat that hardened the blade confined to the cutting edge, thus allowing the other parts of the blade to remain soft and springy.

Using clay could produce a blade without tempering, but usually a light temper was needed to reduce brittleness. The clay also created a beautiful wavy line down the blade (hamon). A perfect hamon was (and is) a sign of an excellent blade and acted as a mark of quality.

The forged blade was passed to the polisher who cleaned and polished the blades using decreasingly abrasive water stones. This polishing could take weeks and is itself a fine art.

The finished blade was then sent for a finely decorated handle and scabbard.

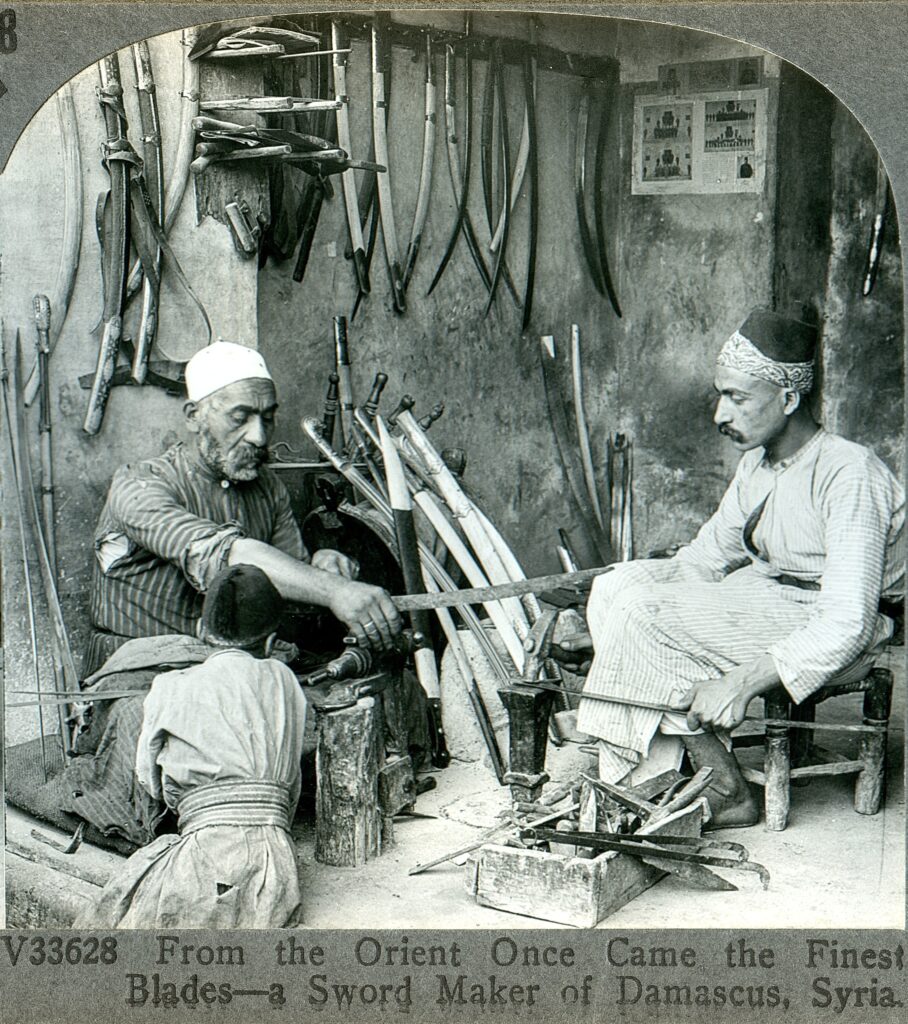

The finest Japanese swords were made by a group of skilled craftsmen. The bladesmith was a Master and directed a group of apprentices. The Master did little of the heavy work, but directed exactly. Often, he would tap the metal with a light hammer and the weight and location of the strike was duplicated by an apprentice with a larger hammer.

The master was there for his skill not his strength. Japanese Master bladesmiths achiveed mythological status and there are many folk tales that describe smiths meeting each other and holding a forging competition. For instance, Muramasa was supposed to have challenged Masamune to see who could make the better sword. Blades made, the two masters hung their swords in a stream. Muramasa’s sword sliced everything: fish, leaves, the air itself. But Masamune’s blade touched nothing. Thinking he had won, Muramasa jibed his master, until a watching monk explained that, while the first sword cut everything, the second, Masamune’s blade, was superior, since it discriminated, leaving untouched that which did not deserve to be harmed. Sadly, this wonderful tale is apocryphal: Muramasa and Masamune were separated by generations and never met.