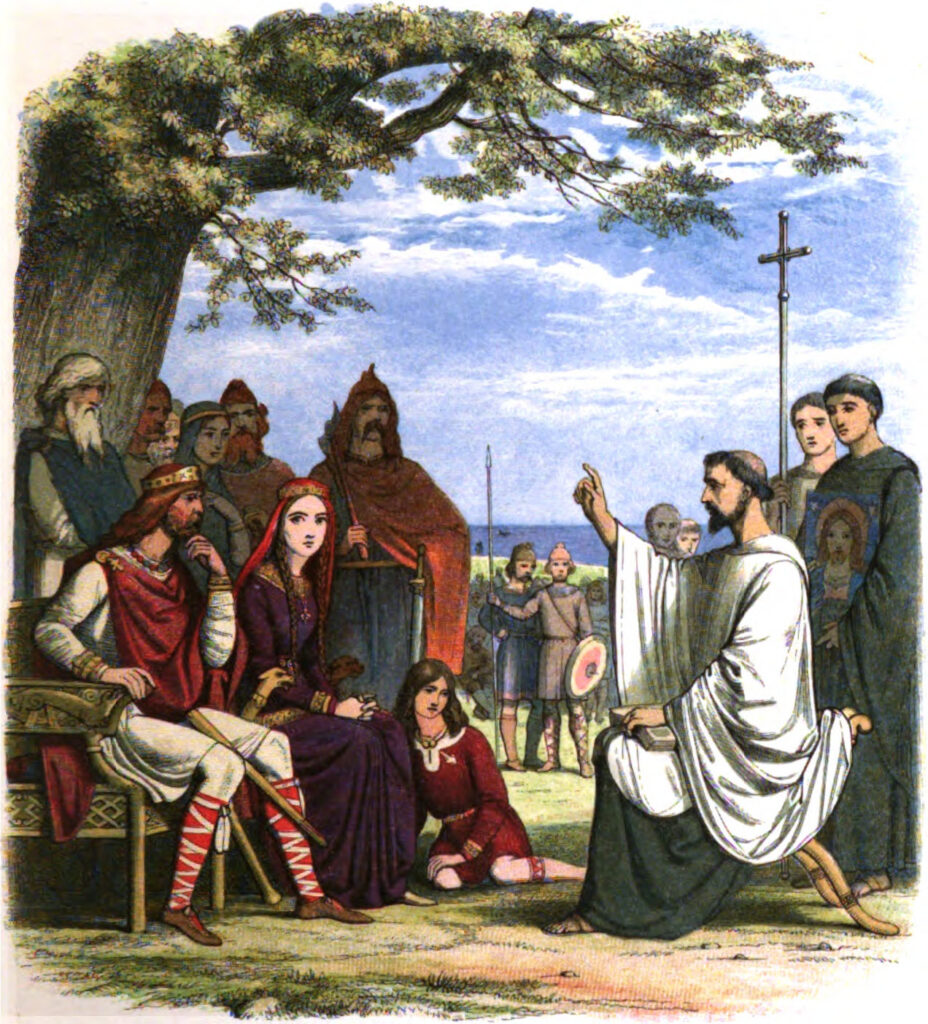

Augustine landed in Kent in 597. It was vital for his mission that he make a good impression on Æthelberht, king of Kent. But when Æthelberht met the strange man from far away, he had many different considerations to bear in mind.

Æthelberht was regarded as Bretwalda, a term which has produced reams of scholarly debate but one that at the least meant a pre-eminence over the other kings in Britain. Usually a Bretwalda owed his dominance to success on the battlefield, but there is surprisingly little evidence for Æthelberht’s military domination, although given his exceptionally long reign (possibly over 50 years) he must have been more than able to hold his place in the shieldwall.

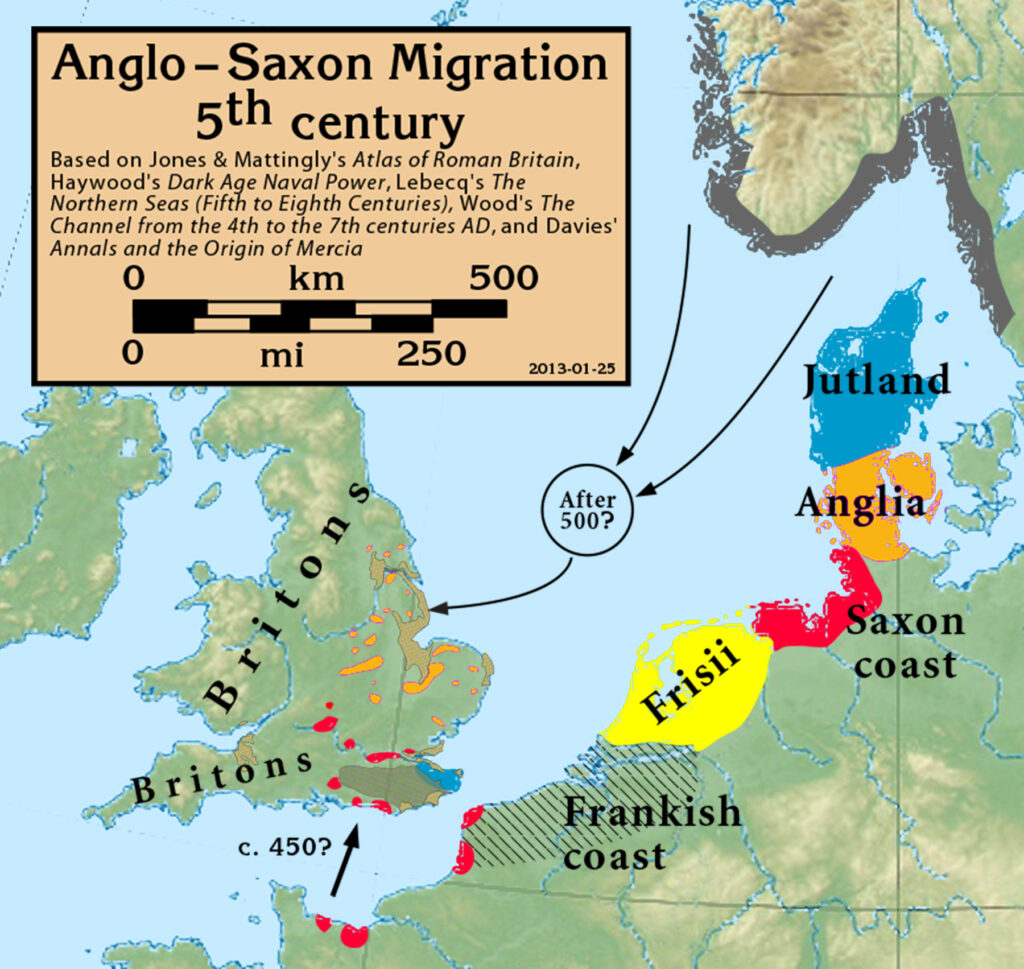

What really gave Kent its dominance under Æthelberht was its links to the kingdom of the Franks, across the Channel, links that had been cemented by Æthelberht’s marriage to Bertha, his Frankish princess. Marriage into the Merovingian dynasty brought Æthelberht great prestige – the Merovingian kings ruled over a vast area when compared with the petty kingdoms of Britain – and access to the continental trading networks and the high-value goods that brought prestige to barbarian kings. Essentially, a king attracted warriors to his court by giving them bling: gold arm rings were most favoured but any shiny gold treasure would attract glory hound warriors to a king’s court. Through his marriage to Bertha, Æthelberht had access to more and better bling than any other king in Britain, and he used these treasures to secure an unprecedented half century in power and his status as Bretwalda.

So it was vital for Augustine to convert the king. While it would be overstating it to say that as the king prayed, so did his kingdom – the king had to keep the support of the witan, the assembly of the most important men in the kingdom – having the foremost king in Britain adopt Christianity would be a huge step towards the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons. After Æthelberht’s initial wariness, as manifest in his decision to meet Augustine away from any structures, the king, under the influence of his queen, accepted the new religion fairly quickly and, by 601, was baptized.

Æthelberht gave his support to the new religion, installing Augustine and his companions in two churches that dated from the Roman era, St Martin’s and Christchurch. With Æthelberht’s support, Augustine’s mission made rapid progress, converting the king of the East Saxons in 604 and shortly afterwards Rædwald, the king of the East Angles, who adopted a rather à la carte approach to religion, keeping altars to both the new god, Christ, and the old gods in his sanctuary.