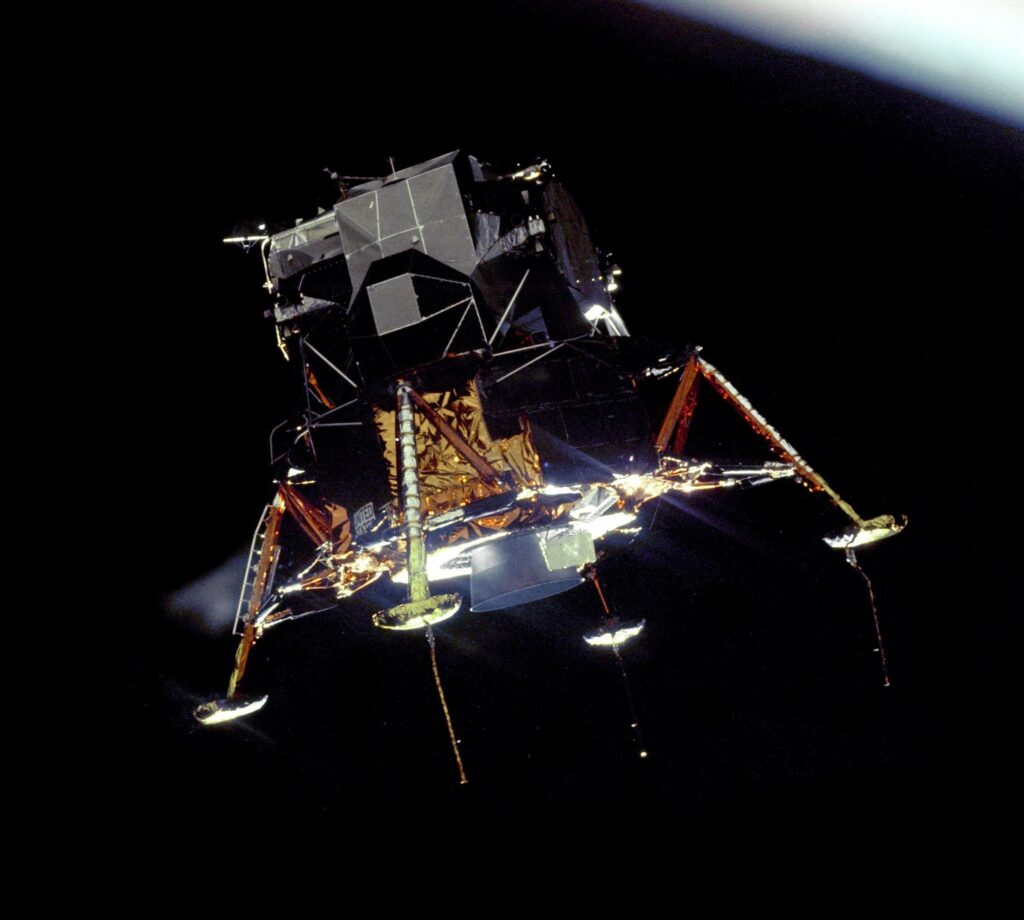

They were 6,000 feet (1,800m) above the Moon’s surface when the alarms started going off. The Lunar Module Eagle was descending far to the west of its designated landing site. Then, looking out of the window, Flight Commander Neil Armstrong saw that the Eagle’s computer system was aiming to land them on the steep slope of a crater made jagged with boulders. The mission to land a man on the moon and return him safely to earth, always a tall order, was beginning to look more and more like it was going to fail.

But that was when Armstrong took control of the Lunar Module. Over his career as a fighter pilot, test pilot and astronaut, Armstrong had been shot down, had the engine of his plane explode and ejected from a Lunar Module simulator seconds before it crashed. He’d survived all these close escapes with nothing more than a bitten tongue and a reputation for never panicking under pressure. Now, Armstrong did what he always did: he stayed calm and played the situation as he saw it. In control of the lander, Armstrong and his co-pilot, Buzz Aldrin, scanned the lunar surface for somewhere safe to land, while the Eagle hovered 500 feet over the lunar surface, riding its rockets. Armstrong moved the craft sideways, searching for somewhere clear to land. They’d been hovering now for 90 seconds. Back on Earth, the mission controllers, watching the fuel supply gauges, were getting worried. Seriously worried. The Eagle had less than a minute of fuel left.

Then they saw it: an area clear enough to land. The Lunar Module descended. 400 feet. 300. 200. 100. 50. 20. Then, one of the probes that dangled down below the landing pads of the Lunar Module touched not earth but Moon. Seeing the warning light on the control panel, Aldrin said, “Contact light.”

“Shutdown,” said Armstrong, cutting the rockets. “OK. Engine stop,” said Aldrin.

The Eagle settled down upon the surface of the Moon, its landing soft under the gentle gravity, only one sixth that of Earth.

Armstrong and Aldrin looked through the windows and saw the dust blown up by their rockets spreading away from them. Outside was the Moon.

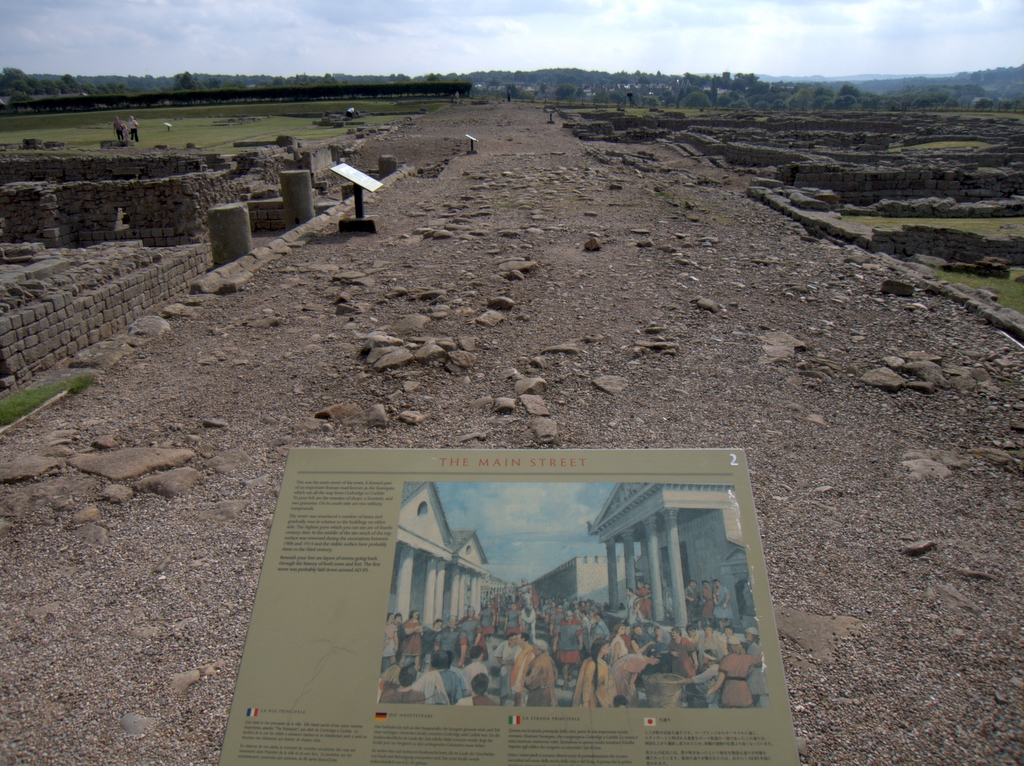

Armstrong got on the radio. “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” It was 20:17 UTC on 20 July 1969. On 17 December 1903, the Wright brothers had made the first powered flight, travelling 120 feet during that first flight. Now, 65 years later, two men had travelled 240,000 miles through space and were about to set foot on the Moon.

Growing up in Ohio in the 1930s, Armstrong (born 5 August 1930) certainly didn’t expect to find himself looking over the colour leached surface of the Moon a few weeks shy of his 40th birthday. But from his earliest childhood, Armstrong had been fascinated by flight. His father took him to an air show when he was two and for his first flight when he was five. Living in Wapakoneta, Ohio (population just over 5,000), the young Armstrong took a job with a local chemist so that he could pay for flying lessons. Already proficient as a flyer, Armstrong received his official flying license on his 16th birthday, meaning that he could fly before he could drive.

Having graduated from high school, Armstrong went to Purdue University where he studied aeronautical engineering as a naval air cadet. Two years later, on 26 January 1949, Armstrong was called up into the Navy and, after flight training, served as a pilot in the Korean War, flying 78 combat missions in Gruman F9F Panthers from the aircraft carrier USS Essex. On one low-level bombing mission, having been hit by anti-aircraft fire and struggling to regain control, the wing of Armstrong’s jet hit a cable – he was only 20 feet off the ground at the time – cutting six feet off the end of the plane’s right wing. Armstrong managed to nurse his plane back into friendly airspace and then ejected. Armstrong’s combat tour lasted from August 1951 to May 1952; 27 of Armstrong’s fellow pilots on the Essex were killed during these missions.

His war over, Armstrong returned to Purdue to finish his studies, receiving a BSc in aeronautical engineering in January 1955. With skills in engineering to match those in flying, Armstrong was accepted when he applied to become a test pilot with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) just before it was renamed the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

As a test pilot, Armstrong flew many of the X planes, the jet- and rocket-powered craft that were pushing airplane technology further, higher and faster. Some of these planes had to be launched from the air and it was while carrying an X plane up to its launch altitude aboard a B-29 Superfortress that Armstrong had another fly past with disaster: one of the plane’s engines exploded, knocking two others out of action, and cutting the co-pilot’s control cables. Armstrong, with one engine working, managed to glide the B-29 back down to a safe landing.

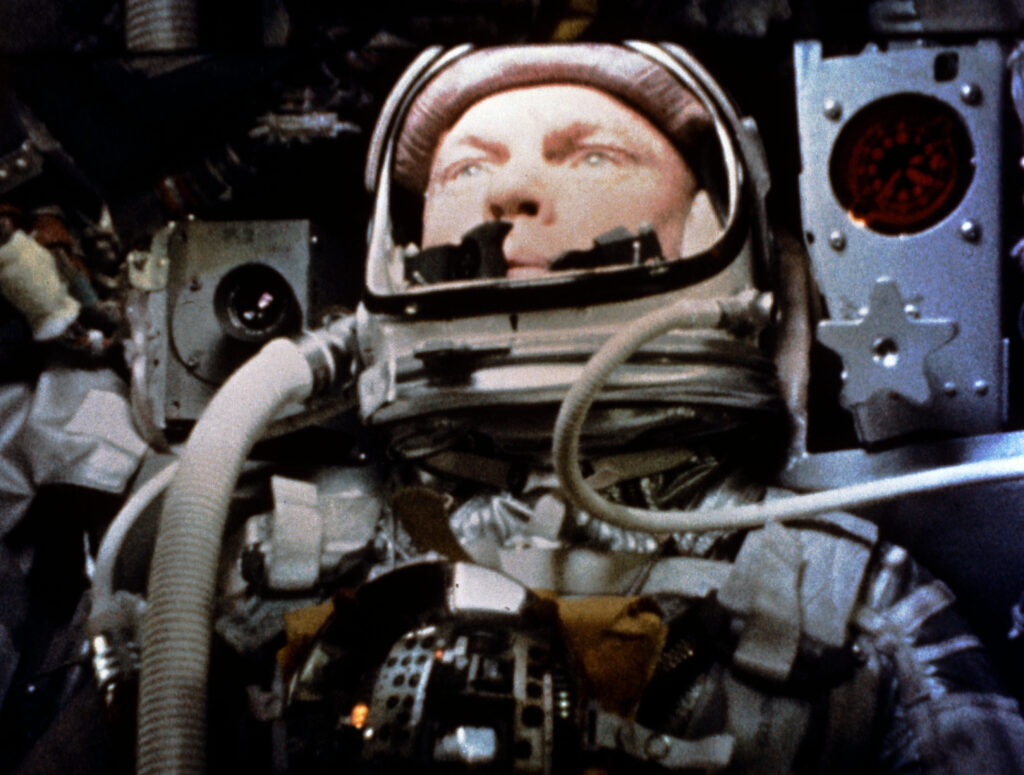

Apart from his many other test flights, Armstrong flew the X-15 rocket plane seven times, touching space and reaching speeds of 4,000mph. He was, in all but name, an astronaut. That title would follow when, in September 1962, Armstrong was selected as one of the second group of astronauts for the NASA space programme. As part of the space programme, Armstrong took part in testing and development, areas where his combination of engineering and flight skills were particularly valuable. On 16 March 1966, Armstrong sat, with Dave Scott, atop the Gemini 8 rocket as it quivered under the 430,000 pound thrust of its engine before firing up, up, up into space. The huge engine generated 6G of thrust but at the end of it, Armstrong and Scott were in orbit. There, they made the first docking in space between their command module and an unmanned target vehicle before a safe re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere.

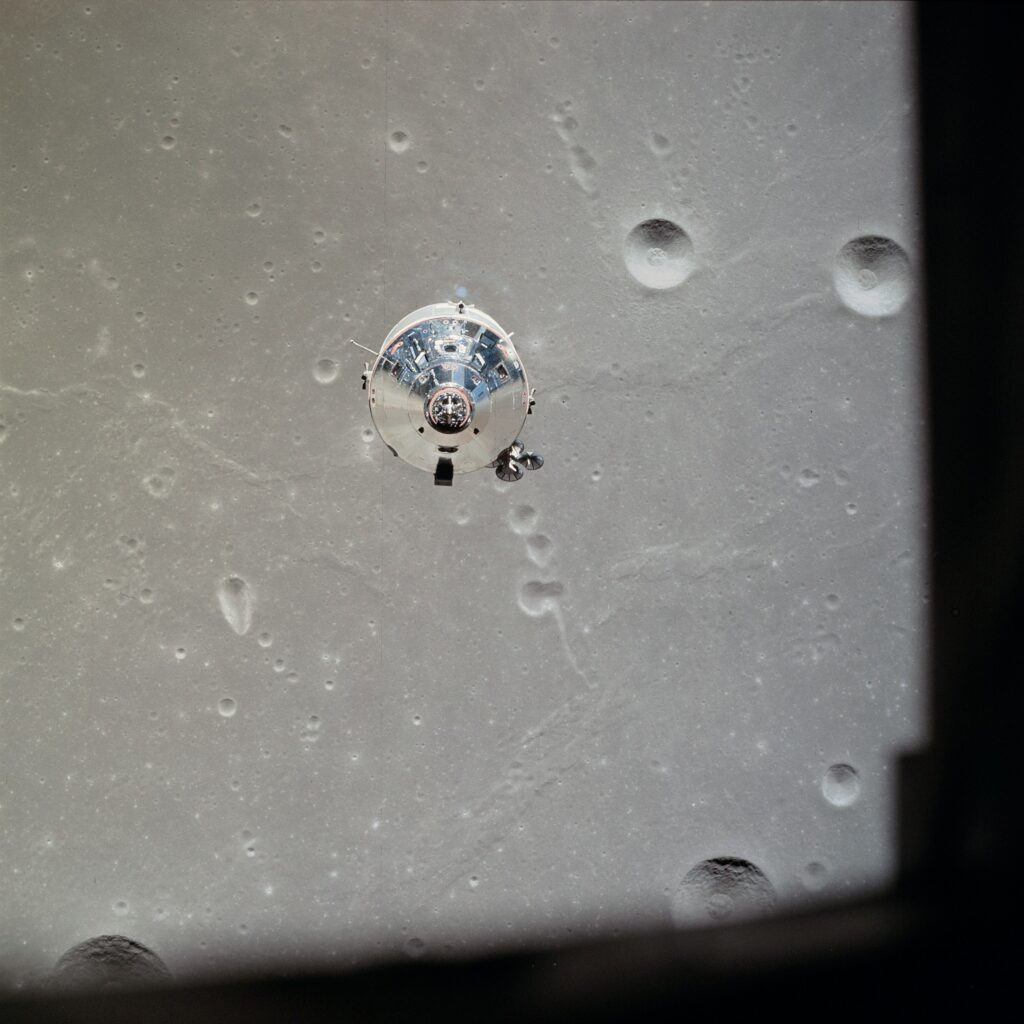

All was set. On 16 July 1969, Apollo 11 with Armstrong, Aldrin and Michael Collins aboard blasted off from Kennedy Space Centre. On 19 July, the mission reached the Moon, swinging into orbit. A day later, Armstrong and Aldrin entered the Lunar Module, leaving Collins in the Command Module to orbit the Moon alone, and began their descent.

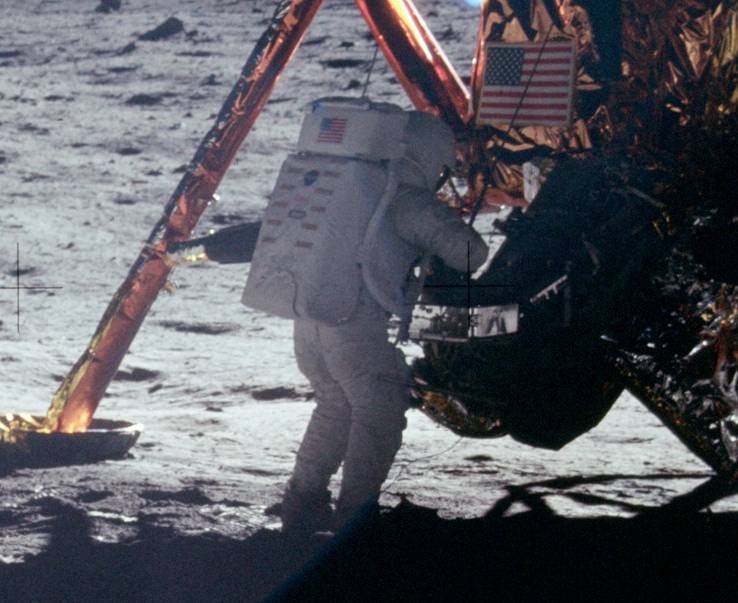

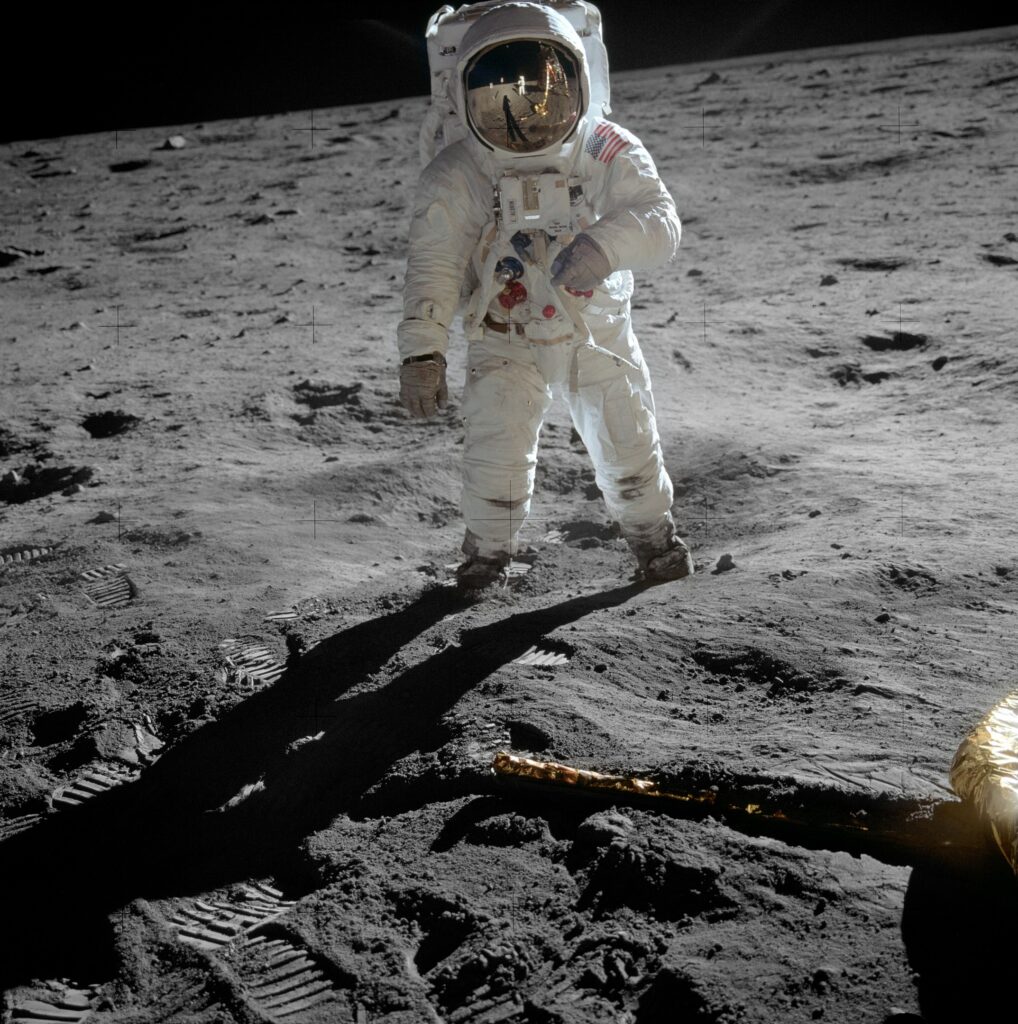

Safely down, NASA’s schedule called for the two astronauts to take a five-hour sleep before leaving the lander as they’d been awake for a long time. Not entirely surprisingly, Armstrong and Aldrin found going to sleep – they were on the Moon! – impossible, and asked for permission to bring forward their EVA (extravehicular activity). Permission granted, the astronauts suited up and depressurised the Eagle. At 02:39 Armstrong opened the hatch and at 02:51 began to climb down the ladder on the outside of the lander. There were nine rungs on the ladder. At 02:56 UTC on 21 July 1969, Armstrong stepped off the footpad and stepped on to the Moon.

“That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”

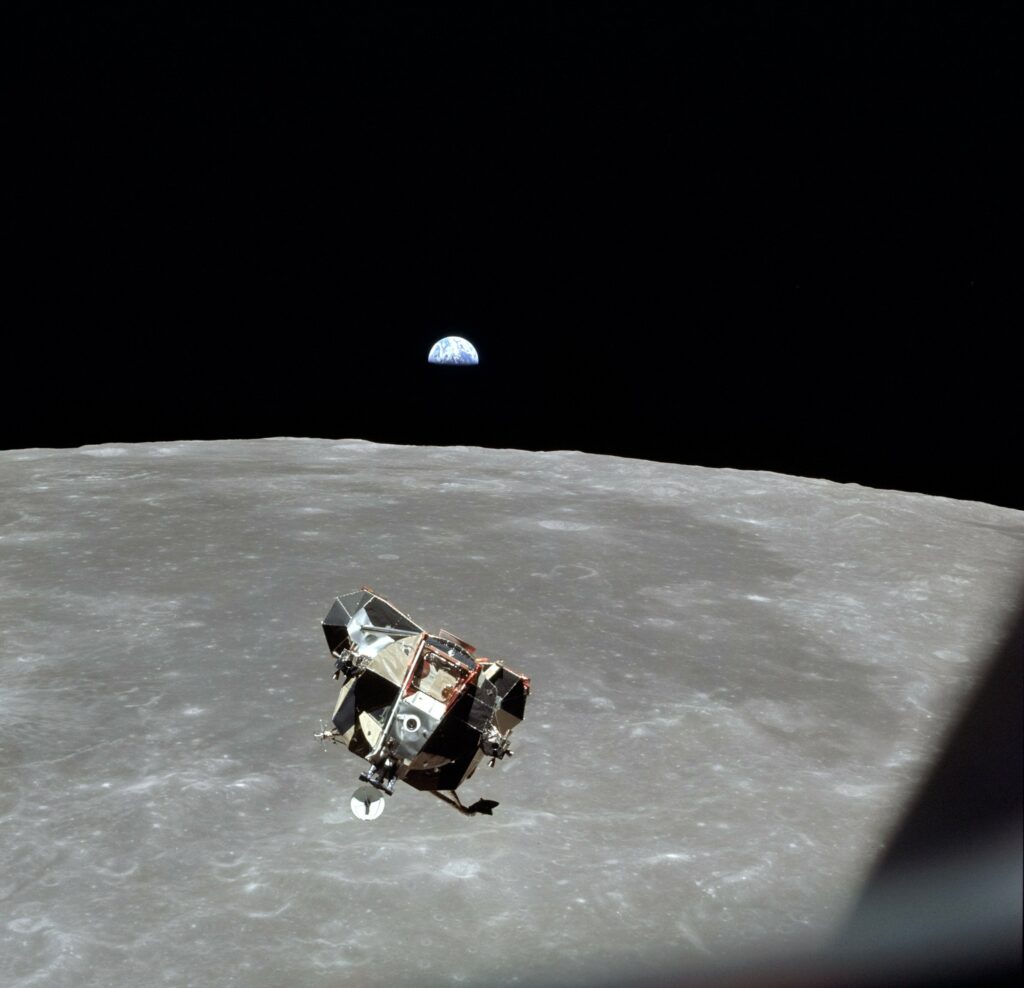

Twenty minutes later, Aldrin joined Armstrong. The two astronauts spent 2 hours, 31 minutes walking on the Moon, collecting samples and setting up experiments. The Earth hung, blue and white, in the black sky. Then they returned to the Lunar Module and settled down to rest. At 17:54 UTC, they ignited the rocket in the Eagle’s ascent stage and took off. Armstrong and Aldrin had been on the Moon for less than a day.

After returning to Earth, Neil Armstrong gave up space flight and left NASA in 1971, taking up a post in the Department of Aerospace Engineering at the University of Cincinnati. He lived a quiet life, generally shunning publicity, and flying gliders from his farm near Lebanon, Ohio. On 25 August 2012, Neil Armstrong died from complications following heart surgery. He was 82.

Between 21 July 1969 and 19 December 1972, twelve men walked on the Moon. No one has done so since.