Edison had invented the light bulb, but he needed to devise a system to distribute electricity to houses and businesses so that they could use his light bulbs. The system he developed used DC (direct current), a low voltage, high current system. George Westinghouse, using ideas developed by Nikola Tesla, came up with a competing system that used AC (alternating current), which used high voltages and low currents.

The battle was on. Tesla had first worked for Edison, but Edison had dismissed his ideas as impractical. However, it soon became clear that the AC system was superior, particularly over longer distances, allowing electricity to be run to remote and rural districts. To fight back, Edison started a campaign highlighting the safety implications of a high-voltage system, going so far as to demonstrate its dangers by inviting journalists to watch when he got a stray dog to stand on a sheet of tin attached to an AC generator. The switch was flipped and the dog yelped and died.

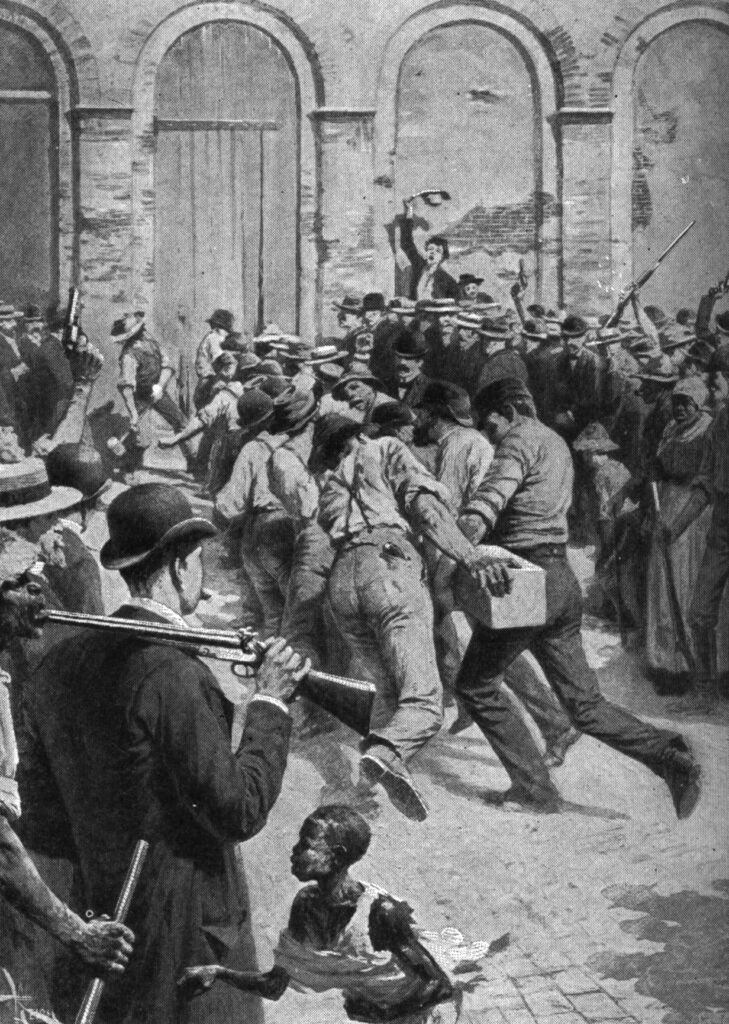

Further support for Edison’s view that AC was a lethal technology was provided when it was used in the first execution of a prisoner by the electric chair. On 6 August 1890, William Kemmler, who had been convicted of murdering his common-law wife, was strapped to a chair and electrocuted. But the first shock did not kill him; it required a second, higher voltage burst to finish Kemmler off, although this set his hair and coat on fire.

Despite Edison’s attempts to tie AC to Kemmler’s execution and brand it dangerous, the system’s superiority prevailed, and in one of Edison’s few failures, the world today runs on AC.