History is difficult without sources. For the two centuries between the Romans leaving in 410 and the mission of St Augustine, who arrived in Kent in 597, we have the barest handful of contemporary documents. It might not matter, if not for the fact that these centuries were the foundation of everything that happened afterwards in Britain: the Romano-Celtic Britannia that slipped out of history at the start of the 5th century reappeared in the 7th century as a country divided, with Anglo-Saxon kingdoms controlling what would become England, Welsh-speaking princedoms in Wales, and Scotland split between Pictish and Irish kingdoms.

Later historians, starting with Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and going on to medieval writers, told the history of these missing centuries, recounting how the pagan Anglo-Saxons had arrived in Britain and displaced the native Britons. But these were histories written centuries after the events they described, and over the last half century historians and archaeologists have grown increasingly sceptical about the value of these accounts. In particular, the findings of archaeologists have served to cast doubt on the one-off departure of the Romans and the ethnic cleansing narrative of the Anglo-Saxon conquest.

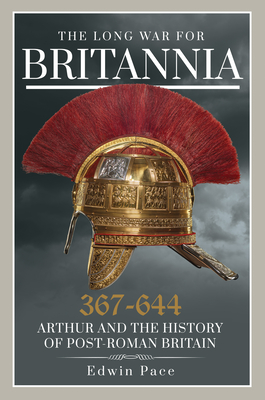

However, on its own, archaeology provides snapshots: it struggles to construct a narrative. Abandoning the ancient sources has left us in an ahistorical darkness, with almost no named actors. In The Long War for Britannia, Edwin Pace has stepped bravely into the dark, mounting a thoroughgoing examination and defence of the ancient sources.

His argument is based in large part upon systematising the differences between the various accounts of the time. Pace argues that many of the discrepancies that have caused historians to discredit writers such as the 9th-century Nennius were caused by mistakes the medieval authors made in trying to fit dates originally calculated by the Roman consular calendar and insular regnal dating into the Anno Domini system adopted by the Venerable Bede. Pace also argues that the key contemporary writer, Gildas, who wrote his On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain around AD 530 by Pace’s reckoning, can be understood by placing his work into the theological framework of the monk. Working off these arguments, Pace concludes that there really was a King Arthur and that he can be identified as the Proud Tyrant of Gildas’ polemic – an unusual but fascinating conclusion.

Pace goes on to identify other people from legend as real historical characters, most notably arguing the Uther Pendragon was actually the 7th-century Mercian King Penda, the last great pagan Anglo-Saxon king. With his mastery of the written and archaeological sources, Edwin Pace has mounted a thoroughgoing and compelling argument for elements from the ancient authors as being worthy of the attention of serious historians. Many historians and archaeologists will disagree with Pace’s conclusions but, together with Miles Russell’s recent book Arthur and the Kings of Britain, there is now a serious, if not necessarily convincing, argument for looking at the ancient chroniclers afresh. Highly recommended for anyone with a deep interest in the roots of England.