In 616, Æthelberht, the first Christian Anglo-Saxon king, died. His queen, Bertha, had predeceased him and he had married again, taking a member of the local nobility for his new wife. When Æthelberht died, his son, Eadbald, married Æthelberht’s widow in an effort to shore up his rule, while abjuring the religion of his father, presumably also to win the support of major families who had not become reconciled to the new religion. There was a similar reaction against the new religion among the East Saxons when their king died. It seemed that the whole mission was on the brink of failure.

However, in East Anglia, a fugitive prince named Edwin had taken refuge with Rædwald. He was being pursued by Æthelfrith, the king of Northumbria (who was married to Edwin’s sister, Acha). Æthelfrith was the most feared warrior king in Britain and, learning of Edwin’s whereabouts, Æthelfrith sent a series of increasingly peremptory demands to Rædwald that he deliver Edwin’s person or his head to the king of Northumbria. Fearful of Æthelfrith’s reputation, Rædwald was on the point of doing so when his wife shamed him into remembering the obligations due to him as Edwin’s host and the man who had given him sanctuary. Rædwald decided to fight. With Edwin beside him, Rædwald rode out with his war band and, catching Æthelfrith by surprise on the banks of the River Idle, killed the man his enemies had nicknamed the ‘Twister’. With Æthelberht but lately dead, this immediately made Rædwald the most powerful king among the Anglo-Saxons, and his first move was to install Edwin as the new king of Northumbria.

The unknown man buried in splendour at Sutton Hoo is most probably Rædwald, king of the East Angles. We don’t know exactly when he died, but it was probably around 624, and with his passing Edwin, king of Northumbria, who had been steadily annexing minor kingdoms since his accession to the throne, was now indubitably the most powerful king in the land. But he was a king in search of a queen, his first wife having died.

Edwin found one in Kent, in Æthelburh, the Christian daughter of King Æthelberht. Eadbald, Æthelburh’s brother, had renounced his pagan flirtation and returned to Christianity. Although not the dominant figure his father was, an alliance with Kent, the oldest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, was a good match for Edwin. As part of the marriage negotiations, Edwin, still a pagan, agreed that Æthelburh, like her mother before her, could continue to practise her faith and permitted her to bring north, as a member of her household, the Italian Paulinus.

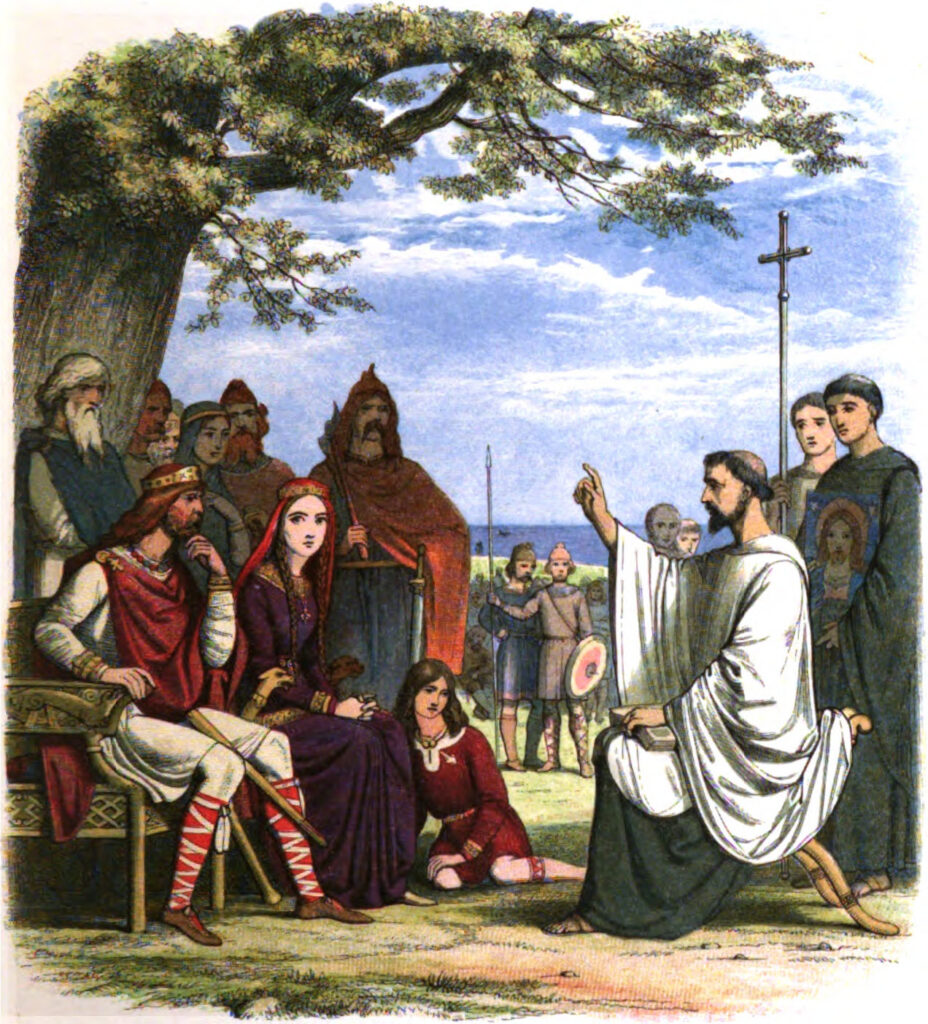

A cautious and careful man, Edwin knew well that this marriage carried the invitation to conversion to the new religion. With his wife and Paulinus as members of his itinerant court, he could consider such a momentous change carefully. In the end, despite signs and portents, the decision came down to whether he could carry his leading men with him. Edwin summoned the witan and the case for the new religion was placed before them. Then, according to Bede, one of the warriors present stood and, likening the present world to a well-lit hall sealed against the winds and cold of winter, spoke of a bird flying for a few minutes into the light and warmth, only to flight out again into the night. Such, he said, was the life of men: of that which comes before and after their life on earth they knew nothing. If the new religion offered greater knowledge of their origins and their fate, then they should adopt it. The witan had been won over.

Paulinus embarked on a mission of preaching and baptising. Edwin had adopted the new faith and, with God on his side, his reign would assure the adoption of the new faith among all the Anglo-Saxons, for the kings all wanted to be winners in this world as much as the next.

But God, it turned out, did not necessarily back his own side. On 12 October 632 Edwin met in battle Cadwallon, the Britonnic king of Gwynedd, and Penda of Mercia, and lost. Badly. Terminally, in his case and that of one his sons, and proximately for another, for he was taken prisoner and later executed.

Edwin’s kingdom fell apart. Queen Æthelburh fled with her young children (the two sons who took part in the battle were from Edwin’s first marriage) and Paulinus went with her, taking ship from York with whatever effects they could carry and sailing back to Kent. Without Paulinus, the religion newly adopted by the Northumbrians collapsed. Penda was a pagan. Cadwallon was a Christian but his animosity towards the Northumbrians was deep and unaffected by their conversion, and the memory of his ravaging lingered long in the kingdom. In despair of the new god, the Northumbrians reverted to their old ones, only for Woden and Thunor and the rest to fail them: Cadwallon killed their new king too.