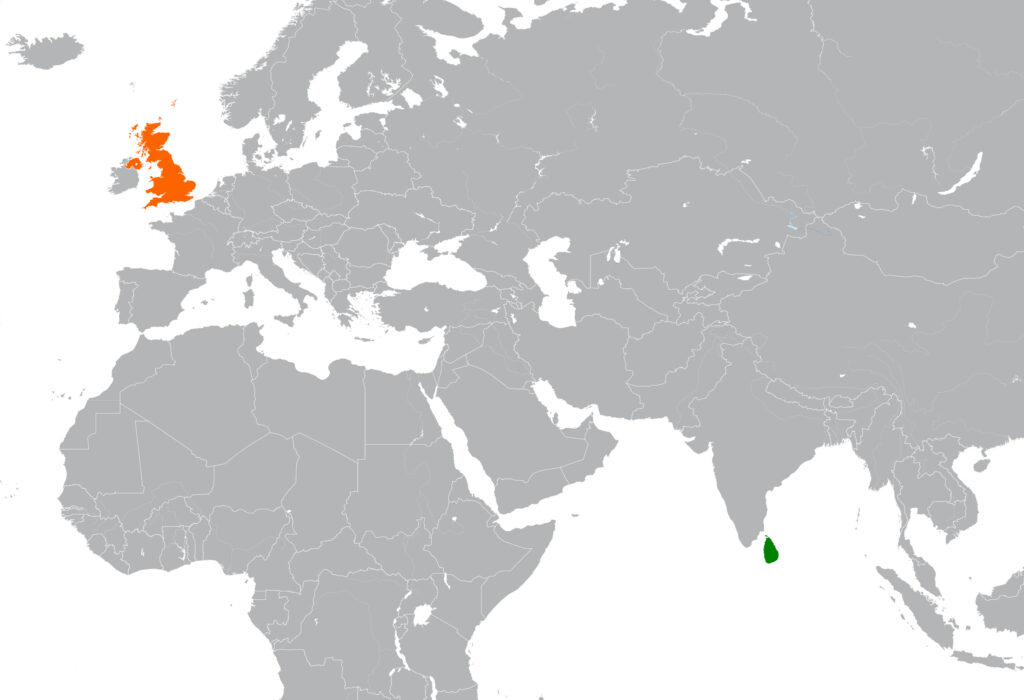

Adam’s Bridge, or Rama Setu, is a long chain of low-lying shoals and reefs connecting a spur from Sri Lanka’s north-east coast to the long ribbon of Dhanushkodi beach running south-west from Pamban Island into the ocean, pointing its long finger to Sri Lanka.

It’s a haunting place to visit. In places the spit of land is so narrow that the houses that remain have the Indian Ocean across their front gardens and the Bay of Bengal lapping against their back gardens. There was a town on the spit of land, reachable by railway. But on the night of 22/23 December 1964, a tropical storm intensified to a cyclone and hit Dhanushkodi town, killing 1,700 people there as well as the 115 passengers aboard the Pamban-Dhanushkodi train that was only a few hundred yards short of its terminus when the storm wave struck, washing the train away. The town was abandoned after the storm and remains uninhabited and largely submerged today.

Trade links between Sri Lanka and India go back to antiquity. Garnets from the island were traded up the west coast of India to the trade ports and held there, waiting for the merchants who sailed over the sea to arrive in the summer, carried by the monsoon winds. The merchants sold their own goods, bought garnets and other commodities, particularly spices, from India and returned with the autumn trade winds.

Having crossed the Indian Ocean, it was a relatively quick passage up the Red Sea before unloading and making the short crossing to Alexandria, where the garnets were sold on to merchants eager to take them further west and north until, finally, the bag of red garnets took ship again, crossing the rough waters of the outer ocean to reach Britain.