Much of the gold that went into Anglo-Saxon jewellery such as the Sutton Hoo buckle was recycled Roman gold, taken from Roman coinage. Rome still had prestige and a nimbus of power that was reflected in the use of old Roman gold as the basis for the jewellery of kings.

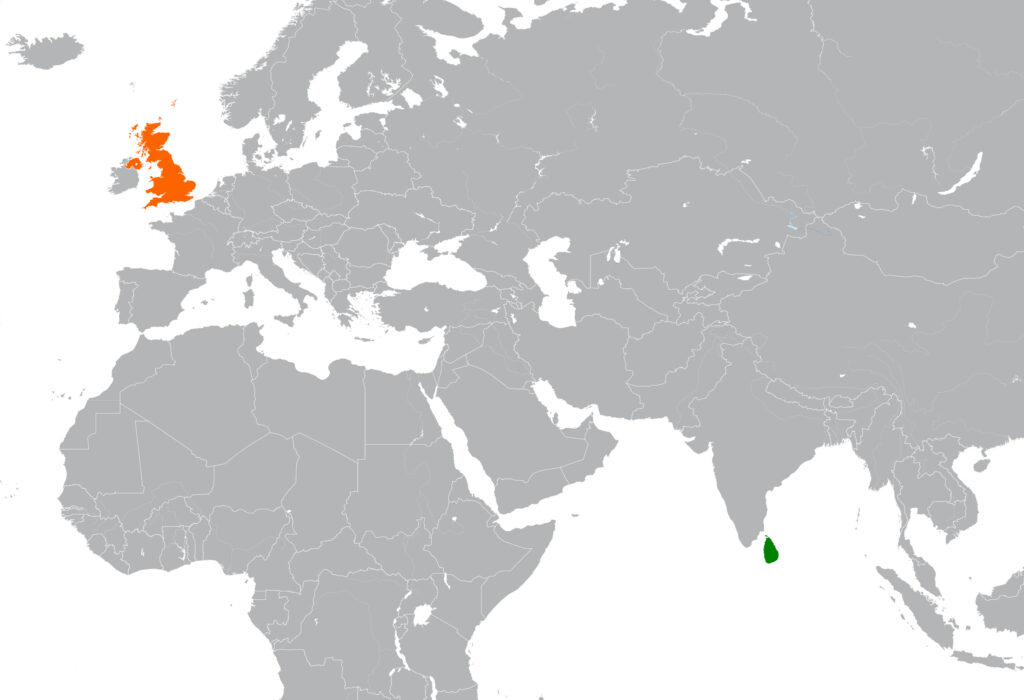

The prestige of Roman gold was greatly enhanced in the seventh and eighth centuries by the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. Rome was both the name of the giants who had made the still hugely impressive ruins that covered the landscape and the present residence of the Pope, God’s representative on Earth, who had, in the person of Gregory the Great, personally sponsored the mission to the Anglo-Saxons. The pilgrim path to Rome was well trodden by Anglo-Saxons from their conversion onwards, beginning with the extraordinarily well-travelled Benedict Biscop – who made five trips to Rome – and continuing throughout the Anglo-Saxon period, culminating in the two trips Alfred the Great made to Rome when still a child.

Of course, few Anglo-Saxons had the resources or time to make the pilgrimage but the fact that Rome existed, suspended in imagination somewhere between reality and Eden, added lustre and gravitas to the remembered Rome while surrounding papal Rome with the nimbus of Empire.