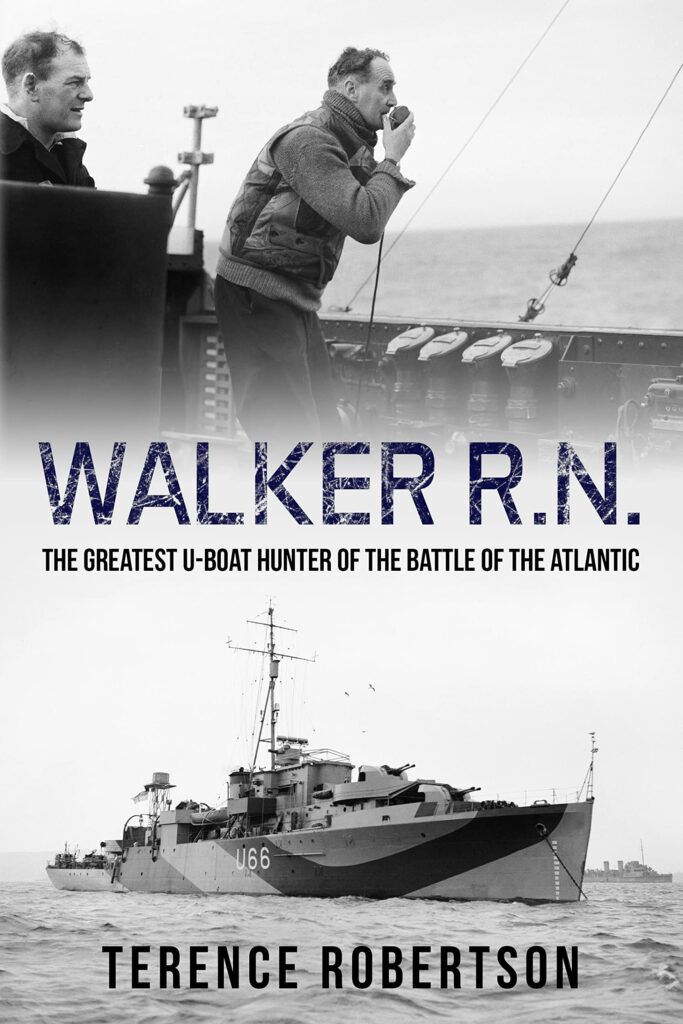

The subtitle tells the book’s theme: the greatest U-boat hunter of the battle of the Atlantic. Frederic John Walker, inevitably nicknamed ‘Johnnie’ after the brand of whisky, was a captain and commander of the small boat squadrons, largely consisting of corvettes and frigates, that were given the task of protecting Britain’s merchant-fleet convoys from German U-boats. Churchill famously said that the Battle of the Atlantic, that long, cold, patient, largely silent conflict that was fought on and under the ocean, was the only battle that kept him awake at night with worry.

Johnnie Walker did as much as any single individual to win the battle. From his revolutionary tactics, where he turned his patrol vessels into the hunters, seeking out and destroying the German submarines, to his unflagging devotion to duty that kept him on the bridge hour after hour, day after day, Walker led the way.

The book is, in some ways, a military hagiography. There’s little in the way of criticism but then, there was little criticism warranted, particularly when you reach the end and read how Walker’s devotion to duty quite literally drove him to an early death. Walker worked himself to death, dying in 1944 when the battle was mostly won but the war not yet over. He also lost his younger son during the war.

The Walker family, like so many others, sacrificed so much that we might live. It is good to remember, and honour, him. And it’s also a thrilling read, conveying well the cold and tension of the long nights when the corvettes searched for the wolf packs, knowing that at any moment a torpedo might come barreling towards them.