Blog

Book review: The Temple Tree by David Beaty

One of the joys of going away on holiday is browsing through the bookshelves of the house or hotel where we are staying. So, on our recent holiday, I was drawing my finger along the spines – sometimes the touch of a book can be as important as its appearance – when I stopped on a slim volume. Drawing it out, I saw a splendidly old-fashioned cover with the much missed Pan logo in the top right corner. But that’s not what made me read the book.

Turning it over to read the blurb, I discovered that the book was set in Ceylon, shortly before it became Sri Lanka on 22 May 1972. That the story involved an air-accident investigator trying to discover the reason a plane crashed on the approach to the country’s newest airport. And that the author, David Beaty, had been born and grew up in Ceylon himself.

Given that my father is Ceylonese (coming to Britain in 1960), and that I visited Sri Lanka for the first time in 1975 with my family, this was an intriguing prospect. Plus, there’s something salutary about reading the forgotten books of forgotten writers – after all, it’s a fate that will probably befall me. I suspect, for a writer, someone reading their books after their death is the equivalent of ten masses for the dead in shortening their time of waiting, so I do hope some of my books might be found, waiting in hope on a dusty shelf after I am dead, taken down, brushed off and read again, bringing ease to the dusty soul of this long-gone writer.

Having finished the book, I did some more research on David Beaty and while it’s true his novels are largely forgotten, it turns out that his research on air-traffic accidents was a crucial influence in ensuring that pilot psychology and crew resource management became essential elements of pilot training. So while his name might be receding, his influence endures.

On to the story. Plus points: I read it in four days, wanted to find out what happened next, and was satisfied with the ending. Negative points: it was rather disappointing in its evocation of post-colonial Ceylon. When we first arrived in Ceylon in 1975, I remember the overwhelming sensation of burgeoning life as we were driven from the airport into Colombo, the sense that one might spit the stone of a fruit out of the window of the car and see the budding tree bursting up out of the ground in the rear-view mirror. What’s more, the story is set during the monsoon season and there’s no real sense of the sweat and the grime, of the way that dirt collects under your fingernails even when you have four baths a day.

So, I am glad to have read the story and, David, I will say a prayer for the repose of your soul. But the story is likely to be left, quietly sitting on old bookshelves, the fading echo of a life’s work.

Book review: The Elder Gods by Stephen Pollington

This is, without doubt, the most thorough examination of the old religion of the pagan Anglo-Saxons available today. Pollington is an independent scholar with all the focus and intensity that sometimes brings, as well as having a good measure of the insularity that is its necessary support. This is the work of a man who has researched the topic as deeply as anyone else in the world and is convinced of the veracity of his conclusions.

For my part, I am just as convinced of the thoroughness of his research but slightly less confident about his conclusions. The evidence for the beliefs and practices of the pagan Anglo-Saxons is so fragmentary and sparse that I suspect the chains of reasoning that underpin some of Pollington’s conclusions could snap relatively easily should some new evidence come to light – not at all impossible, with improving archaeological methods.

Nevertheless, this is certainly the single best book on the subject and one I wholeheartedly recommend.

Book review: All Systems Red by Martha Wells

Right, sometimes you just have to hold your hand up and admit you don’t understand what all the hype is about. The Murderbot Diaries, which begin with All Systems Red, have been a huge success, selling tens of thousands and they’ve even struck writer gold by becoming an Apple TV series. All I can say, is well done, Martha! I wish my books had sold a tenth as well as yours.

But I must admit, I really don’t understand why the lightning of public approval has decided to strike here. The titular Murderbot is a grumpy security android, detailed to look after a crew of planetary explorers. Yes, someone wants to kill them all. Yes, the Murderbot saves them. Yes, he’s still grumpy at the end of the book.

In essence, the Murderbot is Marvin the Paranoid Android with more guns and less wit. It’s enjoyable enough but I remain baffled why this particular SF series should have struck through the clouds of disinterest that surrounds most stories – but then, I couldn’t work out why Twilight or 50 Shades of Grey were huge either. So I’m probably doomed to never knowing sales like the ones Martha Wells is currently enjoying.

So, well done, Martha Wells. I wish I was you, at least for sales.

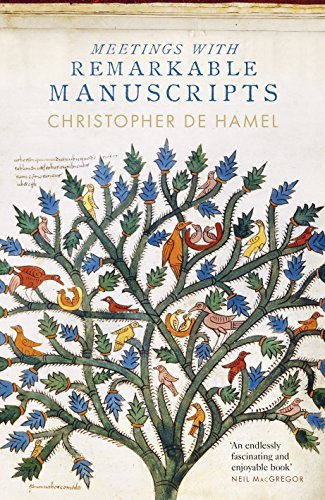

Book Review: Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts by Christopher de Hamel

This is a remarkable book about remarkable books.

There are many joys and discoveries to be made within its pages but perhaps the single most notable aspect of the book is de Hamel’s appreciation of books as physical objects: even the way the pages are stuck together (their ‘collation’ as I learned from de Hamel) provides insights into how the book was made and its subsequent history. But even more, there is the joy that de Hamel so wonderfully transmits in holding a book, turning its pages, examining it and even smelling it. You won’t get any of this with a Kindle!

Perhaps my favourite chapter is the second, the one on the Codex Amiatinus. This is a complete edition of the Bible, a pandect as it’s called in the language of scholars, that was made in the twin monasteries of St Peter and St Paul in Wearmouth and Jarrow in the 7th century, under the direction of the Venerable Bede and Abbot Coelfrith. It’s a huge book, and one that I had a privilege to see at the British Library a few years ago. In fact, it’s as close to being physically intimidating as a book can be – and weighs, as a scholar famously remarked, as much as a female Great Dane. De Hamel got to open it, to read it and to examine it himself – there’s a wonderful description of how he managed to penetrate Italian bureaucracy to get to the book – and that examination revealed details that no reproduction could show, such as the titles on the spines of the books in the famous painting of Ezra in the scriptorium. The chapter also includes the extraordinary history of the Codex, of how it was taken by Abbot Coelfrith as a gift to Rome but ended up in the monastery at Amiatinus in Italy with its dedicatory preface forged to give legitimacy to its new home, and how the forgery was discovered and the book’s true provenance revealed.

For book lovers, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts is essential reading. But this is one book that repays investment: buy the hardback – it’s worth it!

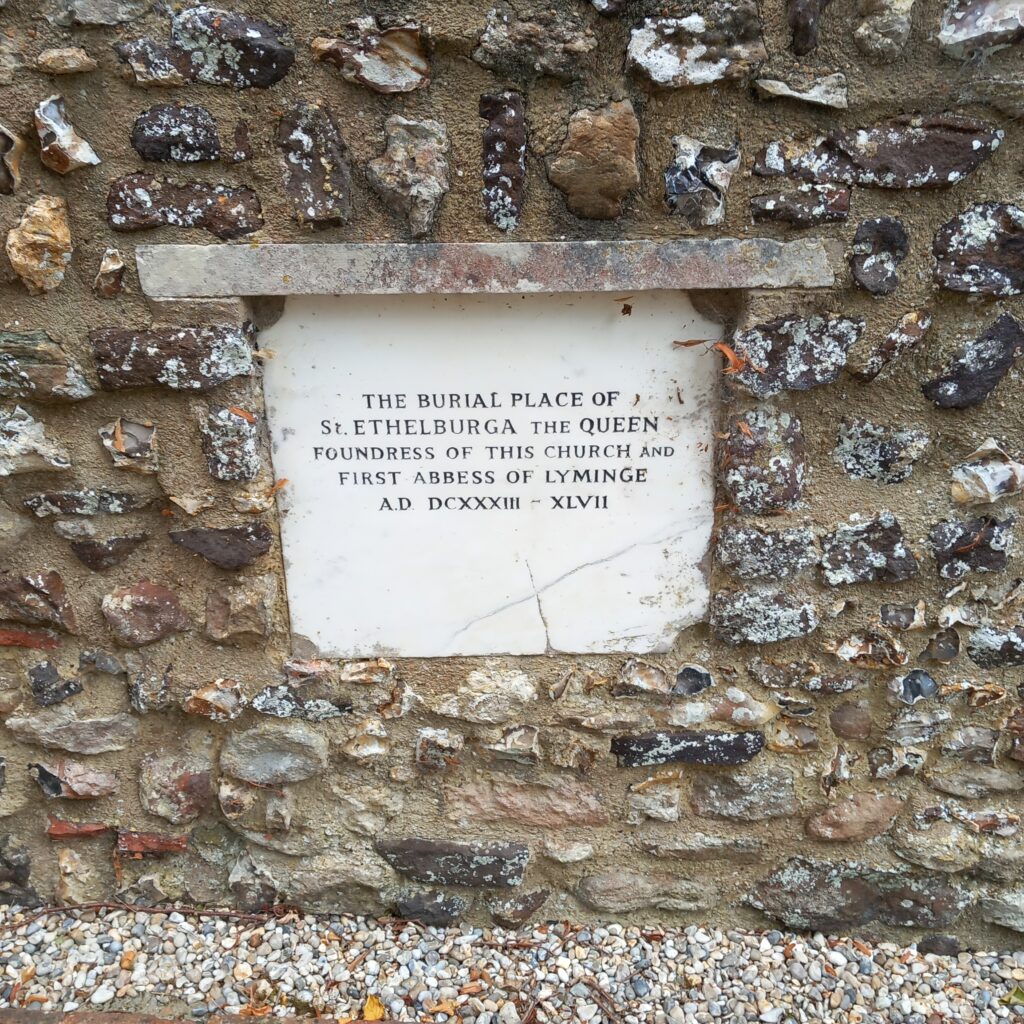

The Resting Place of Queen Æthelburh

Queen Æthelburh is a major character in my novel, Edwin: High King of Britain (she was Edwin’s wife and the instigator of his conversion to Christianity) so I was delighted to visit the church of St Mary and St Ethelburga in Lyminge, Kent, where she founded a monastery and where she was later buried.

It’s a lovely, atmospheric church with an excellent display inside about the extensive archaeological discoveries that have been made in and around the church. Well worth a visit.

Book review: The Beast of Bethulia Park by Simon Paul Caldwell

Real life doesn’t imitate art. In real life, stories get cut off half way through, or sometimes hardly begin at all. Others seem to drag on for far too long. The reason for this is that ‘real life’ only tells part of the story. It’s like reading a book but not being able to read to the end, although exactly how far into the story you can go is random; sometimes a long way, on other occasions to half way, sometimes just a few pages.

This is why, to make art, particularly in the written form of stories, we have to change ‘real life’, we have to tell the whole story so that we, as writers, can create a coherent work of art. We have to ensure that all the story occurs within the confines of the story on the page. But, again, real life isn’t like that.

If it ends at death, then the stories we tell ourselves are just that, polite fictions coined to paper over the bleak reality that there are no stories, that the coherence and the meaning we create with them are of less import than a passing dream that wakes us briefly before we collapse back into the night.

If the story continues after death, then our stories of this world do have meaning, for they acknowledge the incompleteness of our normal human stories by completing them in this world whereas in most cases, the stories are completed only later, their meaning made clear and their climax reached.

In The Beast of Bethulia Park, Simon Caldwell tells a story of this life with reference to the later life, and leaves the events of this life unfulfilled. As such, it’s a story true to the real nature of things but, in one sense, it does not work completely as a narrative because its denoument is, ultimately, off the page of time and beyond the ability of any writer to convey. But in another sense, it does work remarkably well as a story, embodied in time but directed towards the consummation of time.

It’s also a fascinating thriller about doctors with a belief that they alone can deliver life and death – a belief that the current passage of the Assisted Dying Bill throws into an all too believable light.

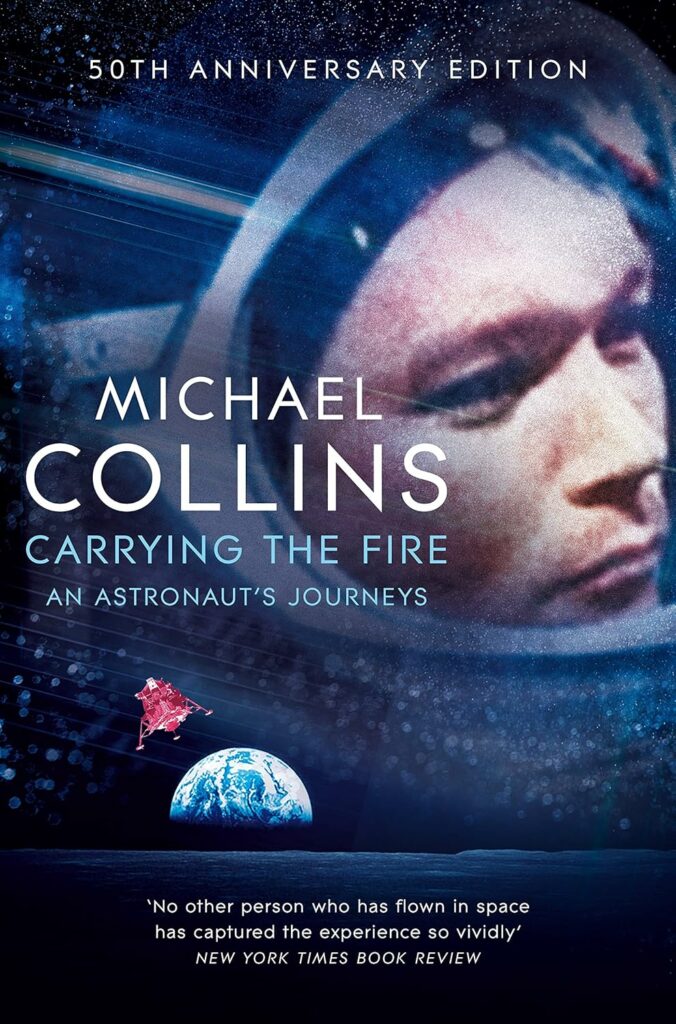

Book review: Carrying the Fire by Michael Collins

On 17 December 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright took to the air in their Wright Flyer, a flimsy contraption of wire, wood and canvas.

On 20 July 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin climbed out of the Lunar Module and walked on the Moon. It had taken 65 years, 7 months and 3 days to go from a 12-second flight above the sands at Kitty Hawk to blasting up through the atmosphere and travelling a quarter of a million miles through the vacuum of space to the moon.

It still seems unbelievable. I can think of no other feat that matches it in terms of technological progress in so short a time.

I was six when Armstrong and Aldrin landed on the moon and I was allowed to stay up late to watch it. But even at the time, I wondered what it was like for the other member of the team, Michael Collins, alone in the Command Module, as lonely as a man has ever been when his spacecraft orbited to the far side of the moon, taking him out of communication, and out of sight, of earth.

Well, this book tells us. And it does so brilliantly. It brings home the sheer amount of work, perseverance and bravery went into the Gemini and Apollo missions, and how many hurdles they had to overcome on the way to the moon. Read it, and marvel at what we were capable of.