Blog

Book review: Crafting Stories from the Past

I’ve been writing books for fifteen years now, with seventeen published, so I was a little dubious that this new how-to book about writing historical fiction would have much to tell me.

Turns out, I was wrong! It has loads for me to learn, in particular about the research side of historical fiction and different ways of organising and remembering all that material so that you can apply it where needed in the writing. I had never even thought of keeping a spreadsheet of historical data. The chapter on what horses can and can’t do, what they need, how far they can travel, and all the other bits of information you need as a writer writing about horses while actually riding around in cars and buses was also invaluable.

The book is written by a collective of writers, with different writers contributing different chapters, so the reader gets the benefit of the distilled experience of many voices. There’s also an excellent appendix with links to further resources for research and writing.

I would genuinely say this is the most useful one-volume guide to historical fiction on the market today.

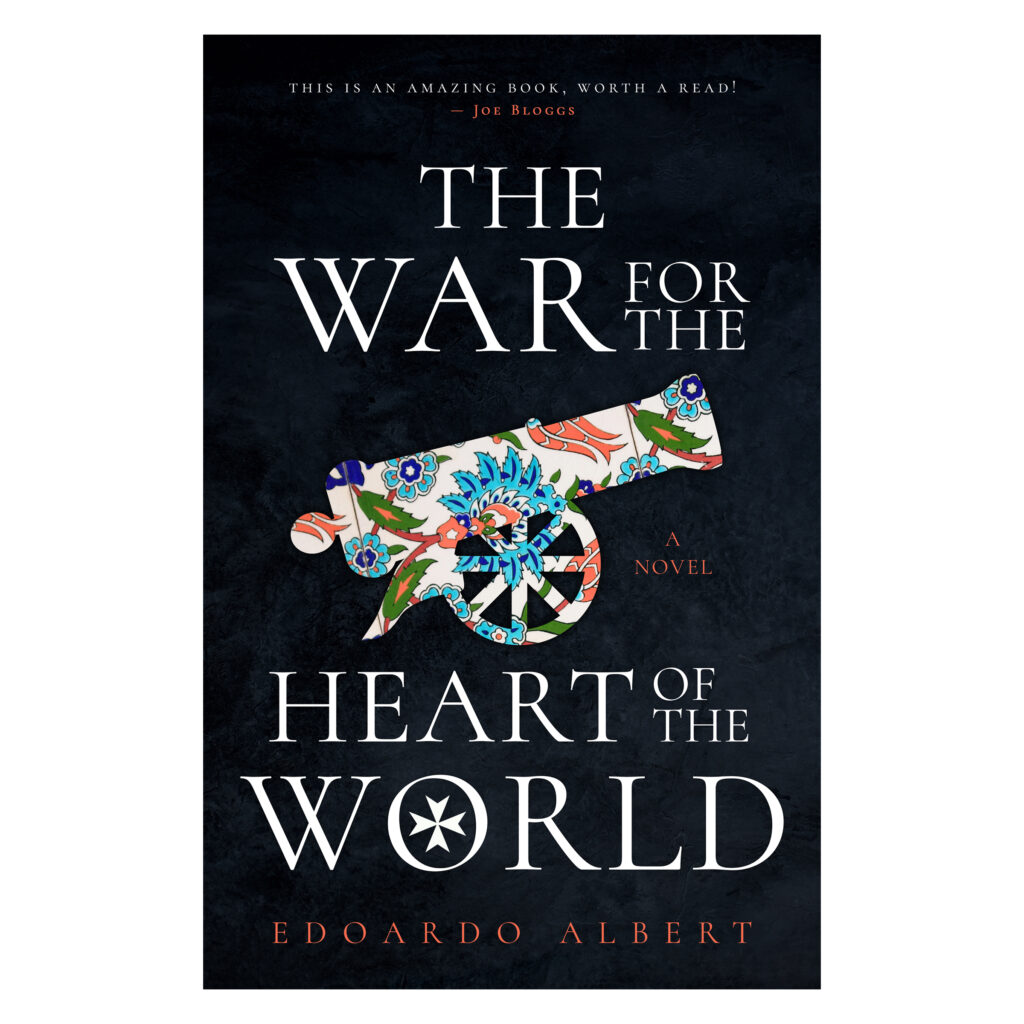

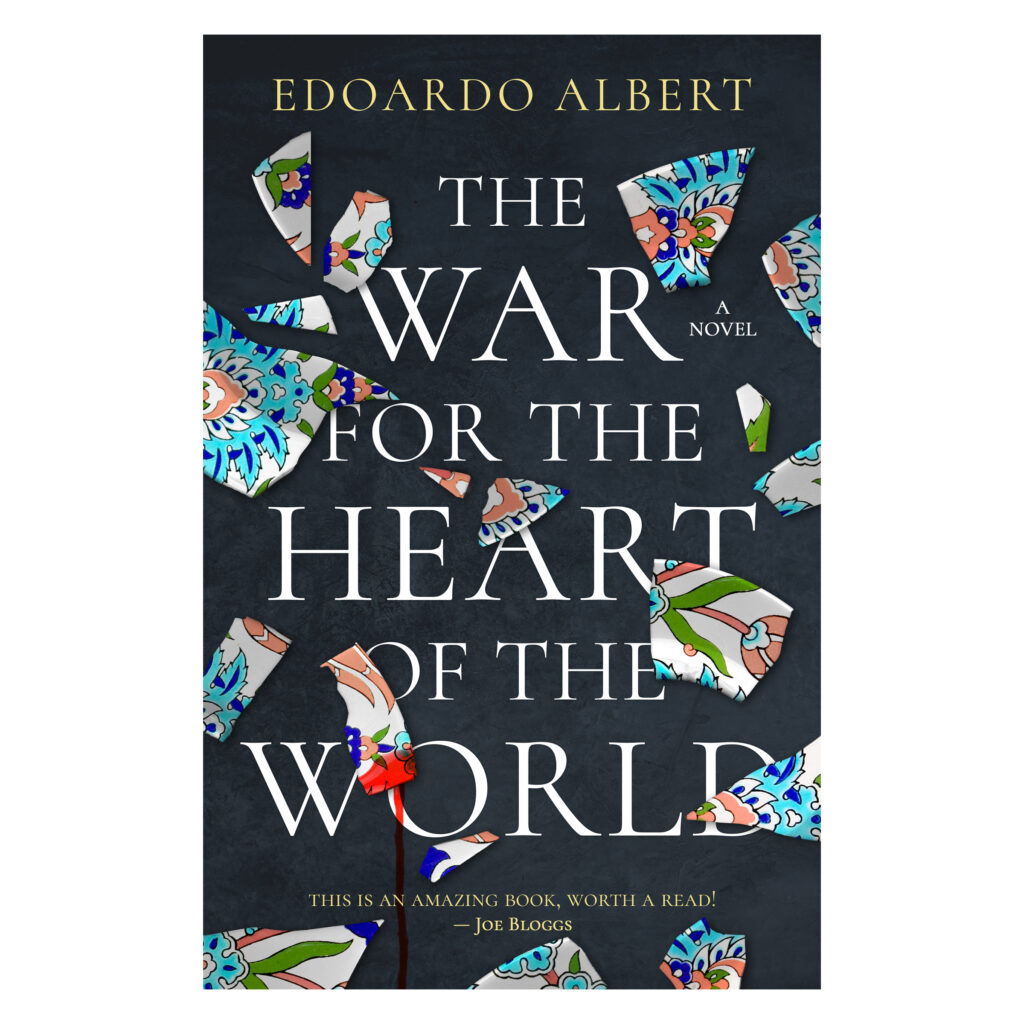

Help Me Choose the Cover for my New Novel

Dear Readers, I would very much appreciate your help. We’re working on the cover for my new novel, The War for the Heart of the World, and my designer has come up with these four concept covers. Which is your favourite? Or, even better, can you tell me your order, from best to worst? It will be a real help to hear from you and learn what you all think.

The Snare of War

Britain was once a place of little kingdoms. By the end of the fifth century, the two Roman dioceses, Britannia Inferior and Britannia Superior, had given way to a mosaic of petty princedoms. Some were the size of a county. Some were smaller: the land around a cluster of villages, perhaps demarcated by some natural features such as forest and river. Many of these tiny kingdoms have left not the slightest trace on the historical record: they disappeared with the deaths of the kings who claimed to rule them. And the reason that so many were forgotten was that the life of a king was short and ended in blood.

For the kings, the men sitting at the apex of the social pyramid, had made a deal with devils in their ascent: having reached the top of the mountain there was no way back down. They were caught as tight as a hare in a wire. It did not matter if their subjects were Britons, Angles, Saxons or any of the other peoples who lived on the land. The farmers were constrained by the rhythms of farming: ploughing, sowing, harvesting, preparing. But the kings were trapped. They were trapped more firmly than any of their subjects.

The kings were caught in the snare of war.

Warriors Born and Warriors Made

Could the son of a farmer become a warrior in Anglo-Saxon Britain? Whether the warrior caste was sufficiently open to allow such a boy to enter it is an interesting question. Certainly, the easiest way to enter the warrior caste was to be born into it. However, it might have still been possible for a farmer’s son to become a warrior and part of the king’s warband.

While the social distance between king and peasant was great, the physical distance was not. The king and his warband were personal and present; they travelled their kingdom. A young man exhibiting strength, courage and initiative could attract their attention, particularly if he had the opportunity to do something that drew attention to his abilities: taking part in a battle and distinguishing himself, alerting the warband to the presence of an enemy, acting as a scout. Any of these could bring the farmer’s boy to the king’s attention and lead to his recruitment into the warband.

Once in, it was deeds that counted. While there was a hierarchy within the warrior aristocracy and the son of a farmer was never going to be an ætheling, his son or his grandson might.

Separated by Battle, Joined by Warfare

The warriors of early medieval Britain – Angle, Saxon, Briton, Irish, Pict – shared much even when they were separated by different religions: following the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons, their cultures converged further.

The threads holding them together ran through language, the hierarchical but meritocratic organisation of the warband, the training necessary for fighting men, the broader horizons established by travel and the many outlanders among them. Indeed, perhaps a majority of warriors learned their skill far from their own mead hall.

It was a common practice for kings in Anglo-Saxon Britain to send their sons, from the age of seven and up, to be fostered as part of the retinue of an allied king. This served to broaden the experience of the growing boy, and it cemented ties between competing and allied kingdoms.

The Rules of Battle

One of the paradoxes of warfare is that for it to occur, the combatants have to share comparable views of how war is waged. They must share the same, or similar, war cultures. Indeed, the whole idea of a determining battle deciding the winner and the loser is part of a particular idea of war that is not universal. Threading it back through the past, it seems to have originated from the internecine warfare of the Greek city states. The citizen soldiers of the city states could not afford to be away from their homes during harvest since missing the harvest meant starvation. So rather than the long-drawn out conflicts of raiding and slave taking that characterised ancient warfare before the Greeks, the armies of the city states met and decided it all in a furious clash of arms, leaving the dead for the dogs and the living time to return home and harvest their crops.

When the Persians invaded Greece, there was a clash of very different military cultures. The Persians did not expect to have to fight set-piece battles with an enemy that would rather die than retreat – withdrawal to fight again another day was perfectly respectable within their military culture. There must have been a consuming feeling among the Persian officers that the Greeks weren’t fighting fair. But it was rather that the Greeks were fighting a different kind of war, and no one had told the Persians.

Meta is Theft

@meta, the company that controls Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, has stolen my work, and the work of countless other writers, to train its AI. It has done so without asking and without paying anything to do so. This is theft. If you would like to register your voice against this, and help to ensure that human writers have a future, please sign this petition: https://chng.it/z2mFLV8HMY

Swords For Hire

It’s plausible that a substantial percentage of an Anglo-Saxon king’s warband were not local men – and that that percentage increased as the fame and renown of the king grew, attracting from further afield young men keen to make their names.

Indeed, this practice was in no way confined to the Anglo-Saxons. The poem Y Gododdin, ascribed to the Brittonic poet Aneirin, tells how the king of the Gododdin called warriors to his kingdom from all over Britain, feasting them for a year in his hall until they launched a doomed attack on their enemy (the battle is now generally accepted to have taken place around 600 and resulted in the defeat of the Gododdin by the Northumbrians).

Spice Run

News from the outside world was one of the currencies a travelling warrior took with him, along with his sword and, sometimes, things to trade. Gifts, particularly portable, exotic gifts, were highly prized and, if small and light, reasonably easy to transport.

Things like spices were ideal. Living in Britain in the seventh century, you would only taste spices when someone returned from abroad bringing a taste of far away. Spices were the ideal gift to bring home since they are light, portable and appreciated in a taste world lacking many of the flavours we know today.